The Dartmouth Observer |

|

|

Commentary on politics, history, culture, and literature by two Dartmouth graduates

WHO WE ARE Chien Wen Kung graduated from Dartmouth College in 2004 and majored in History and English. He is currently a civil servant in Singapore. Someday, he hopes to pursue a PhD in History. John Stevenson graduated from Dartmouth College in 2005 with a BA in Government and War and Peace Studies. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. He hopes to pursue a career in teaching and research. BLOGS/WEBSITES WE READ The American Scene Armavirumque Arts & Letters Daily Agenda Gap Stephen Bainbridge Jack Balkin Becker and Posner Belgravia Dispatch Belmont Club Black Prof Brown Daily Squeal Stuart Buck Cliopatria The Corner Crescat Sententia Crooked Timber Demosthenes Daniel Drezner Dartlog Free Dartmouth Galley Slaves Victor Davis Hanson Hit and Run Instapundit James Joyner Mickey Kaus Martin Kramer The Little Green Blog Left2Right Lenin's Tomb Joe Malchow Josh Marshall Erin O'Connor OxBlog Pejman Yousefzadeh Bradford Plumer Political Theory Daily Info Virginia Postrel Andrew Samwick Right Reason Andrew Seal Roger L. Simon Andrew Sullivan Supreme Court Blog Tapped Tech Central Station Michael Totten UChicago Law Faculty Blog The Valve Vodkapundit Volokh Conspiracy Washington Monthly Winds of Change Matthew Yglesias ARCHIVES BOOKS WE'RE READING CW's Books John's Books STUFF Site Feed |

Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Is Bush Hatred Justified? Why Character Assasination Makes For Bad Politics There seems to be many strands of Bush hatred in the political discourse, which I think warps our perception of politics. The vitriol devoted toward proving that Bush is or is not evil pollutes the ethico-political environment, and transforms politics from deliberation on rational-legal norms to referendum on charismatic leaders. If one buys into Weberian ideal types, it is a historical regression from public rationality to a politics of cults of personality. However, while the mode of criticism is quite sad, the stuff of criticism are those policies about which we have not debated as a society, namely the war and the Bush's unapologetic and divisive leadership after 2000. Two case examples, one criticizing the Bush foreign policy team, and, the other his second inauguration encapsulate this dynamic. Gary Kamiya writes, "In a just world, Bush, Wolfowitz, Rumsfeld, Cheney, Rice, Feith and their underlings would be standing before a Senate committee investigating their catastrophic failures, and Packer's book would be Exhibit A." No. In a just world, these people would be taken out and shot. As for Packer, and his unwillingness to believe his own eyes, he may not realize or admit it, but there were plenty of antiwar lefties who knew before the war that the Bush team didn't have a chance. The fact is that the election of 2000 revealed the Bush team for anyone who was willing to look -- they were and are cheaters -- always willing to use illegality and dishonesty to try to get what they want, and what they want is something for themselves, not for the public interest, whether that public is the American public or the Iraqi public. To a man, they knew nothing about war. The "moral innocence" was theirs. They intended to visit suffering upon some people very far away for their own purposes. Packer and all the pro-war hawks are as corrupt as the neocons are, because they retain some sort of sentimental attachment to their former idealism about whether "war" can be good or bad. A war of independence has to come from those who want to be liberated -- many of us "soft" lefties knew that. This second piece is about his second inauguration, which blends disgust over divisiveness with a critique of competence. George Bush's second inaugural extravaganza was every bit as repugnant as I had expected, a vulgar orgy of triumphalism probably unmatched since Napoleon crowned himself emperor of the French in Notre Dame in 1804. The politics of charisma, however, folds otherwise helpful policy debates into estimation of character and competence, and, aggregates issues that should be considered separately if we wanted to maximize the voter's interest. The fact that many of my liberal friends find Bush to be a dithering toad means that they can write off his successes as luck, and his failures as inevitable. When personalities become the central focus, the opposition's assuredness of themselves acquires a messianic megalomania, convinced of their own rightness and their inevitable triumph. The Democrats, thus, do not need to do anything because they believe that are right, intelligent, and conscientious as opposed to the evil, divisive, dithering dimwitted President. Charismatic politics not only prevents rational-legal discourses, but also impugnes the policies of controversial figures, like Secretary of State Rice, or Senator Hilary Clinton, whose ideas alone qualify them to lead this nation in 2008. Monday, January 30, 2006

Does Being Gay Make You an Enemy of the People? The leftist coalition in America is in tatters. Defeated, desperate, and despondent, Democratic strategic planners look forward to the upcoming battle in November with joy. The plan is to overturn the Republican hegemony in the Congress; and if not overturn, then seriously cripple the ability of the Republican party to rule. The Democrats chances of doing so seem better than ever. As ABC News reports: Americans — by a 16-point margin, 51 to 35 percent — now say the country should go in the direction in which the Democrats want to lead, rather than follow Bush. That's a 10-point drop for the president from a year ago, and the Democrats' first head-to-head majority of his presidency. Naturally, as the election cycle approaches Democrats are searching for someone in their coalition to blame. The going theory for 2004 was that African-Americans failed to mobilize to clinch Democrat majorities in states like Ohio, which enjoy Democrat senators. Even if this theory is true, left-leaning political blacks have little reason to vote for Democrats if race is their primary concern; the Democrat party offers an equal amount of benefits as the Republicans: nothing. Moreover, in places where Democrats enjoy political hegemony, like in Louisiana, the Democrat leaders scheme to remove underclass blacks from New Orleans. "The mostly African-American neighborhoods of New Orleans are largely underwater, and the people who lived there have scattered across the country. But in many of the predominantly white and more affluent areas, streets are dry and passable. Gracious homes are mostly intact and powered by generators. Yesterday, officials reiterated that all residents must leave New Orleans, but it's still unclear how far they will go to enforce the order." Mike Howells, of the public housing rights group C3/Hands Off Iberville, estimates that 3,750, or about half of the city's previous number of public housing units, are either habitable or can easily made so (this does not include the projects like Lafitte with serious flooding). And yet only a few dozen units, at a senior citizens' development, have been officially reopened. This at a time when the Gulf Coast director of FEMA, Thad Allen, is telling the New York Times, "Our No. 1 priority is housing, our No. 2 priority is housing, and after that, at No. 3, we'd put housing." The Democrats, however, are tired of blaming the failure of blacks to  turn-out and vote, and have instead targeted the gays as the source of Democrat electoral woes. turn-out and vote, and have instead targeted the gays as the source of Democrat electoral woes.Frank called San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom’s official civil disobedience an “illegitimate act,” said that “nobody thinks what they’re seeing here is marriage,” and that, come springtime, “we’re going to have actual marriage in Massachusetts.” What exactly are the fights that the Democrats are winning? They haven't persuaded any Republicans to prevent a gross expansion of executive power through either Congressional power or the judiciary. The Democrats largely supported the war in Iraq and provided little by way of anti-war debate. The Democrats supported the Patriot act, and, for the brief time in which they were in control of the Senate (from Summer 2001 to Fall of 2002) did nothing to stop Bush's tax cuts or spending. There's has been a load of crap argument floating around that the Democrats are insufficiently moral to inspire the American, and that the morality focus of the 2004 election swung it in the Republicans's favor. Lucky, the Economist verifies that less voters in 2004 voted on "moral issues." Some Democrat woman, named Molly Ivins, recently declared that she will not support Hilary Clinton for president. Not addressing the fact that Clinton understands that health disparities are just another way the poor get screwed over in America, and that you can't cut domestic political support on troops while at war, Ivins' tirade harps about being deceived by Bush as the main reason not to support Clinton.  She doesn't mention the struggle for gay civil rights, the ethnic cleansing and militarization of New Orleans, or the unchecked presidency. If this is the best the Democrats can offer, maybe we should start voting Libertarian. (The Libertarian party was probably started with this thought: "Hey, let's get a bunch of rich people together and defend capitalism while calling it justice." At least they're honest.) Even the media has stopped reporting on the Katrina disaster, the rampant land speculation, and all the homeless families with children whose quality of life worsens everyday. She doesn't mention the struggle for gay civil rights, the ethnic cleansing and militarization of New Orleans, or the unchecked presidency. If this is the best the Democrats can offer, maybe we should start voting Libertarian. (The Libertarian party was probably started with this thought: "Hey, let's get a bunch of rich people together and defend capitalism while calling it justice." At least they're honest.) Even the media has stopped reporting on the Katrina disaster, the rampant land speculation, and all the homeless families with children whose quality of life worsens everyday.A few Democrats get the message that being pushovers is no way to win an election. [O]n December 6 of this year, San Francisco’s gay Assemblyman Mark Leno, a Democrat, the chair of the legislature’s five-member lesbian and gay caucus, still plans to reintroduce his “Marriage License Non-Discrimination Act” a bill that would legalize gay-marriage in California, regardless of what the court decides. Sunday, January 29, 2006

Is Palestinian Suicide Terrorism Evil? As mentioned before, the Palestinians have elected Hamas--a group dedicated to the destruction of Israel--to an absolute majority in the legislature. Some have commented that the electoral success of Hamas is further proof that Palestinians have embraced suicide terrorism. To me this view--that Palestinian parents would rather celebrate the death of their child if a few Israelis die in the process--and the concomitant debate on the morality of (suicide) terrorism obscures the political nature of the struggle. Let us begin with the election of Hamas. The party's victory can not simply be viewed as a vote for suicide terrorism; it is possible that the Palestinians were simply voting against the corruption of Fatah. (There hasn't been a parliamentary election since 1996.) Let's consider voting in the American context. Many people voted for Kerry in the last election. Was a vote for Kerry a vote for any of the Democratic proposals at the time? Might it not have also been a vote against Bush, that and no more? Hamas has, among other things, provided much needed social services for the Palestinians. As a voter, corruption and vague future promises of peace from Fatah, or, the promise of less corruption, more services, and vague future promises of peace from Hamas sounds like a no brainer to me. However, the objection that Hamas supports and encourages suicide terrorism against Israel (their year long truce notwithstanding) gains further support from the idea that Palestinian society is rabidly anti-semitic. This theory suggests that racism within the territories drives domestic support for terrorism; coupled with victories for a terrorist organization, the racism might lead to more strife. Critics of Israel respond that popular racism is not unique to the Palestinians in this conflict, and thus should not be counted against the Palestinians. Nevertheless, societal racism is not sufficient to explain either the Palestinian use of the suicide tactic nor Israeli willingness (before the late Sharon period) to move populations, flatten homes, and kill Palestinians. The true explanation is that the political elites of both societies were trying to convince the respective populations that longing for control over Palestine was extremely costly. Now both sides are exhausted and wish to disengage. Israeli elites are trying to convince Palestinian elites that the struggle for all of Palestine is futile. The Palestinians are doing the same thing in reverse. Israeli leaders, particularly since the accession of the Likud under Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon, believed that strategic depth of territory was necessary for the defense of Israel. This belief was present in the early days of the state from Jabotinsky and Menachem Begin, on the right, to David Ben-Gurion, on the left. Jabotinsky was much more clear that the creation of Israel would require that either an iron wall be erected between Arab--there were no Palestinians in his narrative-- and Jew in mandatory Palestine, or, that the future citizens of Israel cleanse the Arabs from the land in a sorting process similar to what was happening in post-war Europe at the time. However, we now know that Ben Gurion's pragmatic policy of accepting the UN mandate and waging calculated wars of aggression to defeat the existential threat posed by the Arab armies amassed around the new Jewish state was shrewd. The quick wars of independence gained Israel a foothold but left it without strategic depth-- the minimum amount of land necessary to prevent a blitzkrieg through the state. The wars ended in what have now come to be called the "pre-1967 borders", or, the truce lines of 1949. Students of history will recall the Israeli interventions into Lebanon in 1978 and 1981 and wonder how my theory accounts for those. The Lebanese interventions, as well as decade earlier cooperation with Jordan during its little civil war, was aimed to end the PLO as an organization. After 1967, the PLO, Yasser Arafat's organization, migrated to live amount the substantial Palestinian minority in Jordan, formerly Transjordan, and carry out the same attacks against the Israeli state that first began in the 1950s. However, Arafat, like most refugee organizations in exile, became ambitious and tried to organize a coup against the Jordanian king in what became known as the Black September of 1970. Jordan cooperated with Israel to remove Arafat, and his organization, from Jordan. Arafat then migrated to Lebanon, which, by that time had collapsed into a civil war and continued to harass Israel from its borders. The Israeli armed intervention of 1981 finished what the first intervention of 1978 started; the mission was a success if you limit the parameters of evaluation to whether or not Sharon, then defense-minister, successful ejected Arafat et al. from Lebanon. What the Ministry of Defense did not foresee is that the Israeli army would become the target of Hezbollah, another armed guerrilla group, once the PLO had been removed. Hezoballah also began rocket attacks against Israeli settlements in the occupied territories once the Syrian-backed peace agreement in 1989 ended the Lebanese civil war. (Israeli troops finally withdrew from southern Lebanon under Ehud Barak in 2000.) After the ascension of Yizhak Rabin to the premiership, the Israeli elite began to believe that you could cede strategic depth for protection from insurgencies. However, they did not want the Palestinian elites to believe that they had just run from the fight due to the insurgency, and tried to negotiate a settlement while applying military pressure. Sharon personified this strategy after he ascended to high office and thoroughly killed off militant leadership in Palestine through "targeted strikes" throughout the duration of the second Intifadah. The Palestinians had also modified their strategic goals from 1948 to 2005. Just as the Israelis abandoned their notion of strategic depth--the rhetoric about a return to "pre-1967" borders proves this--so did Palestinians elites shift their goals from the whole of Palestine to a two-state solution. The original goal of the Palestinian political leadership was, as far as I can tell, concocted with the rest of the Arab League and consisted in wiping Israel off the map. As Palestinian nationalism coalesced in the then unoccupied territories, the attacks of the fedayeen (miltants) which plagued Israel from 1950 to 1967 intensified. The fedeayeen fled with Arafat to Jordan after the 1967 war. The remembrance of what the Israelis like to call the "War of Independence" on 1948 as Al Naqba (the disaster) adequately reflects the Palestinian elite's view of what they considered to be a colonial enterprise. 1967 and 1973 changed the strategic thinking of Palestinian elites because they had to go into exile to other Arab states. They used these safe havens to launch attacks on Israeli territory. The dramatic conquest and subsequent humbling of the Israeli military giant in the wars of 1967 and 1973 meant that it was no longer productive for the Palestinian elites to imagine a future without Israel; though it was not impossible to catch the Israelis by surprise, the 1973 war proved that, between their superior technology, brilliant generals (like Sharon), and American support, Israel was an accomplished fact unlikely to change. Thus, the Palestinian elite thinking split three ways. First, there was the old guard, who, with Arafat would go into exile in Jordan, then Lebanon, and then to Algeria and turn to a life of political, though not suicide, terrorism. (Recall the Munich Olympics.) Second, there were the militants who wanted to create a state of permanent insurrection to grind down the Israeli military and resist the growing settlement blocks in the West Bank and Gaza. Like most militants in the region, they became radicalized over time. Finally, there were those Palestinians who pushed for citizenship and inclusion within Israel, or, for political existence along Israel in a separate state. Suggestions that Islam is a culture of martyrdom to explain suicide terrorism, therefore, seems particularly naive because we can't explain the rise of suicide terrorism with sole recourse to Islamic beliefs given that suicide terrorism emerges over time whereas the Islamic beliefs are constant over that period. If Islam caused suicide terrorism, we would have witnessed suicide terrorism from the earliest days of the nationalist resistance, circa 1950. In fact, suicide terrorism emerged as a modern phenomena, first used by the non-Muslim Tamil Tigers; this tactic spread across the word as a useful, effective method of resistance. Now as to why some groups choose suicide terrorism over non-suicide terrorism, I cannot say. What I can say is that all the smoke and mirrors about Muslims wanting to die is large pile of horse pluckey. At the present moment in Israeli-Palestinian relations-- after the death of Arafat and the destruction of most of the political, security, and terror apparati in the West Bank, Lebanon, Jordan, and Gaza, as well as the fence-- the Palestinian elite's will, which encouraged and channeled suicide bombers, has ebbed. This mini history lessons all does to say this: suicide terrorism is not a unique moral question. Either all warfare is murder, or we must recognize that the decision to use force for most politicians and political elites is not a moral question but a political one. It seems silly and a bit imperialist to judge suicide terrorism from a moral point of view as Americans. From the Palestinian point of view, suicide terrorism is a technology in a war of national liberation; it would be facile to demand that the Palestinians deploy tanks, Apache helicopters, and infantrymen to wage their struggle. From Israel's point of view, it is fighting a counter-insurgency against a national liberation struggle. The weight of history--whether industrialized countries generally win counter-insurgency wars against national liberation movements-- is not on its side here. The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is not about morality, racism, or evil--all words often over-used in these tired debates. The conflict is about about the liberation of the destiny of one nation which has found itself in unwilling intercourse with another that seeks its security at the expense of that nation's well being. The struggle is about whether Israel will ever know peace for its children and normalize relations with its neighbours. The war has caused the Palestinians to ask "Need we always be oppressed" whereas the Israelis query "Need we always be pariahs?" It's not clear that ascriptions of evil answers the respective questions of either side. Friday, January 27, 2006

Brief Thoughts on Gavin Menzies Those of you interested in historical controversies past and present will no doubt be aware of the claim that China, under the Ming Dynasty, discovered America before Columbus did. (We'll leave aside what "discovered" implies in this context.) It's chief proponent is Gavin Menzies, an amateur historian who has a book, DVD, and website dedicated to proving his case. (Incidentally, a Chinese world map depicting the Americas has just surfaced; the map is apparently a 1763 copy of an original dating to 1418.) Just about all professional historians, as you might expect, regard Menzies' argument as bunk. As one particularly devastating scholarly review goes, "The reasoning of [Menzies's book 1421] is inexorably circular, its evidence spurious, its research derisory, its borrowings unacknowledged, its citations slipshod, and its assertions preposterous." That's pretty stern stuff for any scholarly journal to publish. Even Holocaust denier David Irving received a handful of favorable reviews in his earlier years, before it became apparent that he was simply bending the evidence to suit his warped view of the Third Reich. Irving also read German and spent as much time digging through the archives as he did manipulating what he found there. Menzies, as his bibliography makes all too apparent, doesn't read Chinese. The cry will inevitably go up, as it already has, that historians are just being snobbish. Menzies's agent said that "a lot of academics have ossified views. They want to protect their own. To them, Gavin is an outsider and they may round on him like a pack of wolves." Well, this claim could be true: there is a whiff of condescension in Fernández-Armesto's review, which I cited earlier. But Menzies's agent doesn't seem to understand that even if the historians are prejudiced against Menzies -- and such claims are, by their very nature, unprovable -- their criticisms may still be valid. And until Menzies demonstrates his ability to rebuff these criticisms as any historian -- professional or amateur -- would, and without resorting to ad hominem attacks, he surely can't be taken seriously. Is Political Islam a Threat to America? If asked about a clash of civilizations, or about the religion of Islam, most policy makers would quickly note that Islam is a peaceful religion embraced by many moderate people seeking an expressive outlet for their faith. After that politically correct caveat, they would then indicate that the real threat to America, and the ideology that undergirds the transnational terrorist network, is something called "political Islam." It's too bad that "political Islam" is not an international menace. The webiste Family.org, which focuses on "social" issues, describes political Islam as a political movement whose goal is the "Islamization of the political order, which is tantamount to toppling existing regimes, with the implication of de-Westernization." The methods and technologies of Islamization can vary between groups; "Some groups advocate violent overthrow as the means of establishing an Islamic order, while others have advocated more peaceful, evolutionary change." Political Islam is also referred to as Islamic fundamentalism, Islamism, jihadism, and militant Islam.  Middle East specialist Daniel Pipes in 1995 specified the dangers of this movement from his point of view: Middle East specialist Daniel Pipes in 1995 specified the dangers of this movement from his point of view: Though anchored in religious creed, fundamentalist Islam is a radical utopian movement closer in spirit to other such movements (communism, fascism) than to traditional religion. By nature anti-democratic and aggressive, anti-Semitic and anti-Western, it has great plans. Indeed, spokesmen for fundamentalist Islam see their movement standing in direct competition to Western civilization and challenging it for global supremacy. Let's look at each of these elements in more detail. On Dan's reading, political Islam is a very dangerous thing. With thousands of years of traditions and symbols to draw upon, the mobolizing power of this ideology is large and should be feared. Moreover, in three major recent elections in the Middle East--Egypt, Iraq, and Palestine--political Islamists have come to power. Palestine and Iraq were the most crushing blows because the Iranian-backed Shiia alliance, and Hamas, an organization classified as terrorist by the United States, won those respective elections. The New York Times succinly captures Bush's dilemma: "The sweeping victory of Hamas in the Palestinian elections threw President Bush and his aides on the defensive on Thursday, complicating the administration's policy of trying to promote democracy as an antidote to the spread of terrorism." After the results from the Iraqi election appeared, sour analysts quickly scoffed: Democracy, however, is not the cure-all for everything. The country remains a security nightmare, with no end in sight to the insurgency. EDIT (next paragraph added recently): Law professor Stephen Bainbridge added his voice to the naysayers suggesting: "The GOP's foreign policy traditionally was dominated by realists and national interest types, who were deeply suspicious of nation building and the like. Bush ran on that platform but after 9/11 veered off into a Wilsonian program of promoting democracy in the Middle East. Now we see what an apparently fair election in Palestine leads to: a decisive victory by a terrorist organization hostile to both the US and Israel. And this is a good thing?" The issue of the results of the votes, however, should be disaggregated from the unproven danger that Islamism poses to America. The results of the elections suggest that even if the ideology of political Islam is not deeply internalized, Middle Eastern voters do not associate the Islamist parties with the corruption of the ruling regimes, and, are willing to vote them into power to target corruption. Voters signaling that they are unhappy with corruption should never trouble the democracy-enthusiasts in the White House. What most policy analyst fear is not that the Islamist will stem corruption, or, at the very least use the corruption to benefit someone else, but that Islamist-dominated regimes will have foreign policy preferences different from those of the United States. The grand strategy of the Bush administration rests on the twin ideas that (1) democracies generally pursue compatible sets of goods, and, (2) their foreign policy objectives will dovetail with the United States. Islamist parties threaten this naive view of how democracies interact in an international state system. Domestically, Islamic parties may impose or incentivize conformity to laws and codes that arise from an "Islamic" tradition. No more threatening to America's national security than if the Anglicans were to sieze power in the United Kingdom, the American voting public need fear nothing from the values of ruling elite insinuating connections to public character and religious belief systems while translating those beliefs into laws and policy. Internationally, Islamist states will face the same pressures as other states. If they act aggressively toward their neighbors, other states will balance against their threat. If they continue to participate in the international economy, investors will send capital their way if their domestic institutions are capital and market friendly. Most succintly, there is nothing particular to Islamist ideologies within states that poses a unique national security threat to the United States greater than that of any other ruling domestic coalition within a procedural democracy. Political Islam as a transnational movement does not present the United States with an existential national security threat either. Commentary after September 2001 understates the degree to which Islamist movements present domestic challenges to corrupt, decaying regimes within the Islamic world. The United States' security is implicated to the extent to which the present governing coalitions remain in power due to American support. The clash of civilizations would be better termed the clash within civilizations, and, is truly no different than the radical race-based movements that challenged legally and socially sanctioned racial hierarchy in American democracy during the 1960s and 1970s. Islamists movements, like the Muslim Brotherhood, primary aim has always been to achieve political power inside their countries and do away clientilistic regimes. Transformational diplomacy, toward the end of encouraging democratic forms of legitimation and domestic institutional structures designed to channel the will of the people, is the correct national security strategy. The slow transitions to voting in the Middle East that do not threaten the political power of the current regimes should fool no one. Rulers in the regions have been faking piety to the divine since Muhammed, just as the elite in Europe and America have faked devotion since the fall of Rome, and could probably similar fake affecting for voting without discovering democracy. Until the economies of the region begin to perform in perform in productive ways for a majority of their population, political Islam will always have a need to struggle against domestic domination. We should encourage this struggle. Political Islam is not a threat to American security; it's an opportunity for democratic values. Thursday, January 26, 2006

Should America Have Accepted Bin Laden Truce? Osama Bin Laden, after months of silence, in a dramatic announcement, offered a truce to the United States. "This message is about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and how to end those wars," it began. The United States responded, through the White House Press Secretary, that the we don't negotiate with terrorists, we put them out of business. However, for the purposes of analysis, let's bracket the Bush Administration's brashness to dismiss this potential olive branch. How should we, then, view Bin Laden's proposal. Dan Drezner suggests that we should this proposal as a joke because it was just a bad publicity stunt. "I'm very wary of sounding triumphalist, but this sounds much more like bad spin control and concern about losing the war than an act of benevolence." Moreover, Drezner observes, "Time's Tony Karon thinks bin Laden has surfaced because he's worried about his own standing among the jihadists: The message — relatively "moderate" by Jihadist standards, in that it appeared to stake out a hypothetical negotiating position and the prospect of coexistence with the U.S. at the same time as warning of new violence — was notable less for its content than for the fact that it was released at all. Despite directly addressing Americans, its primary purpose may nonetheless be to remind Arab and Muslim audiences of his existence, and to reiterate his claim to primacy among the Jihadists.... in the year of Bin Laden's silence, he has begun to be supplanted as the media face of global jihad by Musab al-Zarqawi, whose grisly exploits in Iraq grab headlines week after week.I dunno... this sounds like international relations analysis using the mindset of a Hollywood publicist." Drezner's triumphalism is justified if we assume that Al Qaeda is not in operational control of the insurgents in Afghanistan and Iraq. However, if we allow that Bin Laden's word could affect the resolve of his side's troops to fight, then the triumphalism might be counterproductive. The aim of the United States is to build stable, democratic states in Afghanistan and Iraq. Even if it is possible to export democracy, that project is infinitely complicated by the respective insurgencies. Defeating the insurgency is as much a political question as is a military question-- just like transnational terrorism itself. Bin Laden's leaf suggested that for the first time since 2001, America's conflict with his organization might override two political goals that we both share: the creation of stable states in the region. I don't want to overstate the convergence between Bush and Bin Laden; stable for him means Islamist, whereas stable for Bush means no insurgency, a vote, and a constitution. These two goals, especially for the neoconservatives, diverge but they need not be mutually exclusive. The only things preventing the political strategy of the vote, the election, and constitution from working in both countries are the two insurgencies. Bin Laden offered us a compromise solution whereby we could declare victory and he could cease his jihad. Refusing to negotiate with Bin Laden leaves Washington with only one option: putting him out of business, making political problems of institution and state-building into military problems--defeating the insurgency--where the balance of power is against the external power. If the basic theory behind the intervention is correct--that there exists a silent majority waiting for the prosperity and freedom of market democracy--a rebuilding period would vindicate the neoconservative vision and help the people of both countries. We should have accepted the deal. But not with open arms. If Dan Drezner is right, and Bin Laden is trying to save face, and the United States withdrew, then we would be doing him a huge favor. How do we prevent treachery? Bush should declare that he will remove American troops from Afghanistan (Move 1), and, within three months Bin Laden would have to end operations in both Afghanistan and Iraq (Move 2). If the operations (defined as the insurgencies) ended, within two months of the end of operations, Bush would bring the troops home to America (Move 3 and endgame). In this way, Bush can test whether Bin Laden still has operational control of the insurgency, and, show his willingness for diplomacy. He can also ease the logistical burden on the army temporarily, and, hold another card in his hand against the Iraqi insurgents. In the best possible situation, the war in both states ends, and Bush has two years to rebuild the countries before he leaves office. Monday, January 23, 2006

The posts are going to happen relatively late today. I have one from Friday that I need to finish entitled: "Should America Have Accepted Bin Laden's Truce?" The post for today, assuming that I will write two, is entitled: "Is Political Islam a Threat to the American world order?" Stay tuned for more opinions and fact from me. Thursday, January 19, 2006

Condi's Brilliant Move The Secretary of State has restructured USAID to promote the administration's goals. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice is reshaping the $19 billion U.S. foreign aid program and has appointed the government's global AIDS coordinator to run it. Responding to the criticism that the government's centralization would prioritize short terms goals over long term ones, Rice held a town-hall style meeting in which she: said the position -- director of foreign assistance -- is intended to bring greater coherence and efficiency to a broad patchwork of often overlapping assistance programs that now total about $19 billion. Randall L. Tobias, a former pharmaceuticals industry executive who has headed the administration's global AIDS program for the past 2 1/2 years, was named to fill the position and also to serve as the new USAID administrator. This move is a part of the transformation diplomacy measures. "The foreign assistance initiative is part of a series of moves announced by Rice this week under the banner "transformational diplomacy." Her plan, announced Wednesday, to redeploy U.S. diplomats from Europe to difficult assignments in the Middle East, Asia and elsewhere received some backing yesterday from the American Foreign Service Association." Of its many blunders, the Bush Administration has had excellent success in picking its Secretaries of State. Will Congress Act to Limit Presidential Powers? The Senate Democrats have begun to speak out against Judge Samuel Alito, whom, this blog has noted before, is going to be bad news for America. CNN notes: The Democrats said they believed Judge Samuel Alito would fail to check what they view as the president's inappropriate expansion of executive power. The Republicans, however, control a 55-seat majority caucus in the Senate, and moderate Republican Arlen Specter has announced that he is in favor of the nominee. Given the amount at stake in this nomination on the subject of executive power, the Democrats must filibuster the nominee. However, the Washington Post , in "More Democrats Say They Will Oppose Alito" reports: A procession of Democratic senators, including two who supported the confirmation of Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., said yesterday that they will oppose the nomination of Judge Samuel A. Alito Jr. to the Supreme Court. They warned that he would not provide a judicial check against the expansion of presidential power or be properly vigilant about protecting the rights of ordinary Americans. The New Republic (registration required) has come out swinging against the nominee noting: More important in our view are the central questions of the confirmation hearings: namely, Alito's views about congressional and executive power. We were especially troubled by Alito's vote to strike down the federal ban on the possession of machine guns, on the grounds that Congress had not offered convincing evidence of a connection between machine-gun possession and interstate commerce. Indeed, in his hearings, Alito emphasized that, in his view, Congress needs to explicitly identify the effects of its laws on interstate commerce for them to pass constitutional muster. Alito reaffirmed his view that the Supreme Court's 1995 decision striking down the federal ban on guns in schools was a constitutional "revolution"--a development he seemed to view as positive. And he refused to say that all of the Supreme Court's Commerce Clause decisions of the past 50 years are "well-settled precedents," allowing only that "most" of them are settled. Showing little of Roberts's emphasis on the importance of judicial deference to Congress, Alito raised fears that he would join Scalia and Thomas in overturning a host of federal laws. After all, many of the cases upholding congressional power during the last 50 years are arguably inconsistent with the original understanding of the Constitution; and, if Alito is willing to deny Congress the power to regulate machine-gun possession, it's not unreasonable to fear that he might deny Congress the right to regulate drug possession or protect the environment. Executive power is not the area in which Alito falls short, but at the moment, it is the most important. Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Is Israeli Settler-Colonization the Functional Equivalent of the Holocaust? I. How Should We Remember the Holocaust? Jonah Goldhagen provides an excellent example of a problematic analysis of the Holocaust in his book suggestively titled Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. Goldhagen, in analyzing the Holocaust in comparative perspective, often wrote of the German “willingness to kill” Jews during World War Two. For him, the preceding Holocaust scholarship’s inability to describe adequately why the Holocaust happened in Germany obscures the obvious and underlying German hatred of Jews. He begins: “[Other explanations of the Holocaust] ignore, deny, or radically minimize the importance of Nazi…ideology, moral values, and [their] conception of the victims for engendering” a basic desire to hate and kill Jews. (13) Goldhagen’s theory, in contrast, comments on the deep nature of German anti-Semitism to explain the Holocaust: “the perpetrators, ‘ordinary Germans’ were animated by anti-Semitism, by a particular type of anti-Semitism that led them to conclude the Jews ought to die.” (14, emphasis in the original) The German hatred of the Jews had become so great, and his opinions of the Jew so low, that the Holocaust was the only possible answer available to the German Jewish Question. “Simply put, the perpetrators, having consulted their own convictions and morality, and having judged the mass annihilation of the Jews to be right, did not want to say “no” [to genocide].” (19) Goldhagen puts much effort in trying to prove that the Germans were particularly anti-Semitic to the point of requiring the eradication of the Jewish race. For him, the conflict between German and Jews began in the early pre-school propaganda of children’s books, “The Devil is the father of the Jew”, and ended in the morbid oblivion of the abattoir. Moreover, even though “the Jews of Germany…wanted nothing more than to be good Germans” and the “Eastern European Jewry [was extremely] Germanophil[ic]”, in his mind it was not surprising, in retrospect, to have observed the Nazi mass slaughter because “the will for the comprehensive killing of Jews in all lands” was a result of the race hatred of divided German society. (414) There are two problems with casting the Holocaust in this light. The first is that nearly 72% of Germany's Jews, through institutionalized discrimination and cultural intimidation, were forced to emigrate before the Germans initiated World War Two. (Browning, The Final Solution and the German Foreign Office, 14.) The second problems involves the curious little fact that the mass annihilation of European Jews, as opposed to merely German Jews, or, on the other hand, all Jews, did not begin until 1941. The German government targeted Jews because it genuinely believed that the Jewish people, as a political-biological entity, posed an actual threat to the German national future in the form of Marxist-Communism, on the one hand, and as a degrader of that pure Aryan blood, on the other. Hitler warns in Mein Kampf : “If, with the help of his Marxist creed, the Jew is victorious over the other peoples of the world, his crown will be the funeral wreath of humanity and this planet will, as it did thousands of years ago, move through the ether devoid of men.” (300) With such rabid, delusional, and psychotic anti-Semitism—from which a large number of our European counterparts currently suffer to a lesser degree—it is quite logical to intuit how the Nazis could be responsible for the murder of so many Jews. Though logical, the mass murder of Jews was not the sole option for the Nazi. In fact, it was not even the first option. The first option chosen by the rabidly anti-Semitic Third Reich was that of institutionalized legal and cultural discrimination. In order to protect those Germans from the Jews, the Reich abolished Jewish political and economic rights. Exclusion of Jews from service in the government, the practice of medicine, participation in the academy, and the holding of any positions of power and influence become commonplace in pre-war Germany. The ban on German-Jewish intermarriage flowed naturally from the aforementioned cases of discrimination. Forced emigration became the immediate aim of the German government after all the institutional discrimination was in place. The SS Security Service memorandum nicely summarizes early German Jewish policy: “the aim of Jewish policy must be the complete emigration of the Jews…[T]he life opportunities of the Jews have to be restricted, not only in economic terms. To them Germany must become a country without a future, in which the old generation may die off with what still remains for it, but in which the young generation should find it impossible to live, so that the incentive to emigrate is constantly in force.” (Friedlander, Nazi Germany and the Jews, 201) This policy was so successful that almost three-quarters of Germany’s Jewish population emigrated to safety from that totalitarian nightmare. By 1942, however, Germany began on a campaign to mass exterminate many of the Jews. Why? There are three pieces of evidence which I believe addressed my second question. First, the success of the German blitzkrieg across Europe brought millions of Jews, enemy combatants in their eyes, under its control. The amount of energy needed to convince Germany’s relatively small number of Jews to emigrate would have been insufficient to have dealt with the millions now on their hands. The refusal of other European (and American) nations to accept more Jewish refugees, combined with the lack of places to which Germany could deport Jews, created many logistical problems for the Nazi bureaucracy. Himmler, the architect and guardian of Nazi deportation policies, drafted a statement in 1940 stating: “I hope to completely erase the concept of the Jews through the possibility of a great emigration of all Jews to a colony in Africa or elsewhere…[H]owever cruel and tragic…this method is still the mildest and best, if one rejects the Bolshevik method of physical extermination of people out of inner conviction as un-German and impossible.” (Browning, Nazi Resettlement Policy, 3-27, emphasis added.) A few months later Himmler clarified: “biological extermination…is undignified for the German people as a civilized nation.” After the German victory, “we will impose the condition on the enemy powers that the holds of their ships be used to transport the Jews along with their belongings to Madagascar or elsewhere.” (Browning, Nazi Resettlement Policy. 16-17; Gotz Aly, Final Solution: Nazi Population Policy and the Murder of the European Jews, 3) Mass extermination was “practical” for two reasons. First, the Germans were used to destroying entire civilian populations for logistical reasons. In France and some areas of Eastern Europe the Germans limited their killing to exterminating rivals and rebels whereas in the areas of Eastern Europe that had been designated Lebensraum entire populations were destroyed or depopulated. Accordingly, Nazi rule exposed “all of them to alien rule, and some to deportation, terror, and mass murder. Very, very few people wanted the Germans there, regardless of how they conducted themselves under occupation.” (Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History ,426) Michael Burleigh further noted that the future German plans toward France and the western countries were extremely destructive. “Hitler was interested in German dominance of the continent, with a view to exploiting its resources for his great schemes in the East, not in some sort of amicable partnership….At the height of their power the Nazi leaders were contemplating the disappearance of some of Europe’s smaller states and the drastic attenuation of France herself, which they regarded as the hereditary foe, linchpin of Versailles, and a source of democratic ideals which they had just comprehensively vanquished.” (Burleigh, 426) Second, the Germans had already effectively emptied Germany of the mentally ill and deformed. Adapting gas chambers and methods of extermination to the most recent problem was a small technocratic challenge, easily overcome by the German bureaucracy. By the end of 1942, Germany had already murdered about two-thirds of the Jews, roughly 3.8 million, that it was going to murder under the Final Solution. (We also still have to deal with the fact that a large number of Jews who died during the Holocaust, whom I included in this estimate anyway, did not die from shooting, hanging, phenol injection, or gassing but rather from sickness, disease, undernourishment, and hyper-exploitation. If we were to speak of Jewish deaths in the same method by which we speak of aboriginal deaths in the Americans during the Spanish conquest, these would not count toward the Holocaust total.) II. What Is Israel Doing to the Palestinians, or, What is the Holocaust's lesson for Israel? Arthur Chrenkoff opines: “Where does one even begin to tackle this sort of absurdity? That if there is "not much of a difference" between the Second World War and the Second Intifada, where are today's concentration camps, where is Auschwitz, where are the gas chambers and the crematoria, where are the mass graves, where are the Einsatzgruppen and the SS? Or maybe it's not that Germans don't know what the Israelis are doing to the Palestinians - maybe they don't know what their own grandfathers have done to the Jews? Maybe Germans think that the Holocaust consisted of Wehrmacht shooting a few Jewish kids throwing stones at the Panther tanks, or Luftwaffe taking out a Jewish Fighting Organisation leader in retaliation for a suicide attack on a Munich beerhall?” I agree with Chrenkoff that the Israelis are not fighting a war of extermination against the Palestinian people. I, however, would like to ask Chrenkoff if drawing comparisons between “the Second World War and the Second Intifada” are as “absurd” as he would like them to be. For instance, the discrimination and disenfranchisement of Israeli Arabs in Israel’s 50 plus years of existence has been comparable to Nazi disenfranchisement of Jews before it starting killing them. The expulsion of Arabs in the Arab-Israeli wars, the encourage emigration that is still an official Israeli policy, and the confiscation of Arab possessions during this conflicts is not dissimilar from pre-war Nazi policies. The once active settler policies of various Israeli governments, both right and left until Sharon, after the 1967 Six Day War, is eerily similar to the German settler policies unleashed on Eastern and Western Europeans during the Second World War. Moreover, the explicit preference given to Jews worldwide, similar to the German preference given to Germans in all lands, smacks of the Nazi past. (Naturally, we would have to consider the removal of settlers in Gaza as a positive step toward ending the siege against the Palestinian people.) Let me be clear here. I am not arguing, as it is fashionable to do these days, that the Jewish state will be setting up death camps anytime soon. I, however, see the almost mutually exclusive tensions generated by the two pillars of Israel: of being (1)a democracy (2)for the Jews. Almost as problematic as the conservative Christian notion of salvation for all persons (excepts prostitutes, liberals, Jews, gays, etc), the Zionist idea of a democratic state for Jews, built in land which, until recently has not had a Jewish majority for some millennia, suffers from the centrifugal forces of inclusion (democracy) and exclusion(ethnicity/religion). As a recovering Zionist myself, I struggle with how Israel should keep its Jewish majority and remain democratic in the face of a demographic shift against its ideal. Ariel Sharon's commendable withdrawal from Gaza last summer was a step in the right direction. But what of the larger settlements in the West Bank and what of Jerusalem? Lesser regimes would have engaged in mass killing in the face of organized para-military resistance and a population explosion of an “enemy nation.” Comparisons to the Nazi past are not only relevant, but necessary, that Israel may guard her heart against the seductive strategic logic of mass killing. III. What are the lessons of the Holocaust for the world? The world made a pledge to “never again” let the Holocaust happen. “Never again” has turned into an almost universal expectation that every person should actively and consciously recall the gruesomeness of the Holocaust to prevent future genocides. In so far as the world has stood by time and time again when multiple mass killings explode around the globe since World War Two—in communist states starving their people to death between purges, in fundamentalist terror in the Middle East, in anti-colonial revolutionary struggles, in Western armed interventions into other states, in anti-communist liquidations, in counter-guerrilla operations, and in ethnic conflicts—I am starting to believe that the promise was actually “Never again in 1942 will we allow Germany to kill Jews.” Benjamin Valentino, in his book Final Solutions proposes a solution to this mess: “Only by comparing the Holocaust to other episodes of mass killing can we asses its significance. Only by understanding its similarities and differences can we draw lessons from the Holocaust that might help us prevent or limit this kind of violence in the future. Indeed, the contribution that studying the Holocaust can make to the understanding of genocide and mass killing in general is one of the most important reasons why honor our obligation to never forget it.” Elie Wiesel: “I have tried to keep memory alive, I have tried to fight those who would forget. Because if we forget, we are guilty, we are accomplices.” We should remember the Holocaust, then, in so far as it helps us to understand the mass terror that mass murder unleashes upon the world, whether by Western governments in poorly planned interventions and calculated hate, or by political instability. Jean Baudrillard: “Forgetting the extermination is part of the extermination itself.” Tuesday, January 17, 2006

Is Saddam's Tribunal Doomed? On Saturday, the chief judge of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's tribunal, Rizgar Mohammed Amin, tendered his resignation as a judge. Judge Amin is a Kurd, one of the many ethnicities butchered by Hussein's regime, who had committed himself to procedural fairness. Interrupting neither Hussein's tirades nor the emotional stories of victimization from countless witness, Amin committed himself to upholding the legitimacy of the court through impartiality. The principal source of irritation for Amin, however, came not from Hussein's repeated denunciation of the court, but from the interim government. The government's position, not altogether unreasonable, was that since we know Saddam is guilty, we should attempt to hang him as quickly as possible. News Telegraph reports: "Ministers, including the justice minister, had publicly chastised him for allowing Saddam to make repeated outbursts, while also saying that the trial should be speeded up and Saddam executed as quickly as possible." Having turned in his resignation days ago, analysts predict that without Amin, the tribunal will lose its dignity and appearance of impartiality. The court now faces the daunting task of replacing Mr Amin, who, despite the criticism levelled at him, is generally considered among the more capable Iraqi legal minds willing to work for the court. Replacing Amin is Said al-Hammashi, who "was born in Baghdad in 1952 to a Shia family, said one of his colleagues, speaking on condition of anonymity. He graduated from the law department of Baghdad University and went on to become a practising lawyer during the Saddam regime, which was brought to an end by the United States-led invasion in March 2003, the colleague said. Mr Hammashi was later sent to Italy and Britain to learn more about crimes against humanity in preparation for the Saddam trial." Why is the new regime, now having faced elections, determined to hang Saddam quickly? It seems that with the Baath party destroyed, some Kurdish autonomy gained, and an American commitment to defeating the insurgency, the government should concern itself more with socioeconomic matters of services and political matters of inclusive representation. However, the new regime is concerned more with the prospect of a living Saddam as a Napoleon who returns from exile and undoes all their hard work. The soon Saddam hangs, the sooner the regime can blame the old one for its shortcomings. In Class until very late today and tommorrow; daily update to occur very close to midnight for both Tuesday and Wednesday. Monday, January 16, 2006

How Domestic Pressures Against the Iraq War Will Cause Mass Killing War is a messy business in which civilians will die. However, modern technology has given soldiers a much greater control over the physical effect of the weapons of war. This control, with sufficient planning and supplies, greatly reduces the unintentional casualties of war (collateral damage) and allows modern industrialized nations to wage war while upholding the principle of distinction. Notice that I mentioned planning and supplies, suggesting that a war waged either on the cheap, or without popular political backing, reduces the ability of soldiers to distinguish between civilians and combatants, and increases the amount of civilian deaths during times of war. Political pressures on the Bush administration have caused it to 1) make a strong case for the war to keep some public support and 2) begin talk of "drawing down" troop levels in Iraq. These troops generally refer to infantry and armor divisions of the Army, who's main task right now is to kill insurgents, capture territory from hostile elites, remain in control of that territory, and provide welfare and infrastructure for the population. The infantry divisions are aided by air support; air power, based primarily on aircraft carriers in the Indian Ocean, allows the armed forces to project military power more quickly in ways that limit American casualties and to provide intelligence on the movements of enemies. As the troop levels reduce, Washington will project military power through its air war to the detriment of the lives of civilians. Seymour Hersh, writing for the New Yorker, suggests: "A key element of the draw down plans, not mentioned in the President’s public statements, is that the departing American troops will be replaced by American air power. Quick, deadly strikes by U.S. warplanes are seen as a way to improve dramatically the combat capability of even the weakest Iraqi combat units. The danger, military experts have told me, is that, while the number of American casualties would decrease as ground troops are withdrawn, the over-all level of violence and the number of Iraqi fatalities would increase unless there are stringent controls over who bombs what."  The basic problem is simple: the Administration needs to continue prosecuting the war vigorously while reducing troops. The Clinton and Nixon administration provide models for warfare with lower American casualties: Kosovo and Cambodia, both of which relied heavily on air power to do the dirty work. No one doubts the President's resolve to bring "freedom" to the Iraqis; Bush, however, must do something about the mounting casualties, the overstretched armies, and the perceived global overreach of his Administration. Hersh observes: “We’re [the Administration] not planning to diminish the war,” Patrick Clawson, the deputy director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, told me. Clawson’s views often mirror the thinking of the men and women around Vice-President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. “We just want to change the mix of the forces doing the fighting—Iraqi infantry with American support and greater use of airpower. The rule now is to commit Iraqi forces into combat only in places where they are sure to win. The pace of commitment, and withdrawal, depends on their success in the battlefield.” Moving to an air war further conflates political and military objectives in target selection. With Americans picking the targets, the politics of the situation demands selecting targets who seem to be insurgents and whose removal does not unduly cause civilian casualties or ruptures in relations with civilians leaders. If American ground forces become secondary to Iraqi forces, and the Iraqi military leaders are selecting the targets, these choices occur with the context of a highly contested civil war. "Air Force commanders, in particular, have deep-seated objections to the possibility that Iraqis eventually will be responsible for target selection. “Will the Iraqis call in air strikes in order to snuff rivals, or other warlords, or to snuff members of your own sect and blame someone else?” another senior military planner now on assignment in the Pentagon asked. “Will some Iraqis be targeting on behalf of Al Qaeda, or the insurgency, or the Iranians?”" The shift to air warfare from ground warfare is even more frightening when considering how under-reported the air war is. The American air war inside Iraq today is perhaps the most significant—and under-reported—aspect of the fight against the insurgency. The military authorities in Baghdad and Washington do not provide the press with a daily accounting of missions that Air Force, Navy, and Marine units fly or of the tonnage they drop, as was routinely done during the Vietnam War. One insight into the scope of the bombing in Iraq was supplied by the Marine Corps during the height of the siege of Falluja in the fall of 2004. “With a massive Marine air and ground offensive under way,” a Marine press release said, “Marine close air support continues to put high-tech steel on target. . . . Flying missions day and night for weeks, the fixed wing aircraft of the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing are ensuring battlefield success on the front line.” Since the beginning of the war, the press release said, the 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing alone had dropped more than five hundred thousand tons of ordnance. “This number is likely to be much higher by the end of operations,” Major Mike Sexton said. In the battle for the city, more than seven hundred Americans were killed or wounded; U.S. officials did not release estimates of civilian dead, but press reports at the time told of women and children killed in the bombardments. Michael Schwartz adds: One of the true scandals of media coverage of the war in Iraq has been the simple fact that you -- relatively small numbers of you anyway -- had to visit Tomdispatch.com, or Juan Cole's invaluable Informed Comment blog, or Antiwar.com, or other Internet sites to find out anything about the fierce (if limited) ongoing air war in that country. The American media's record on coverage of the air campaign against the Iraqi insurgency since Baghdad was taken in early April 2003 has been dismal in the extreme. Our military has regularly loosed its planes in "targeted" attacks on guerrillas in Iraq's heavily populated urban areas (where much of the fighting has taken place), sometimes, as in largely Shiite Najaf and largely Sunni Falluja in 2004, destroying whole sections of major cities, in part from the air. Despite this, American reporters in Iraq have essentially refused to look up, or even to acknowledge the planes, predator drones, and low-flying helicopters passing daily overhead. Air power, without a ground presence doing a Jenin-style door to door search, harms American efforts to win over the population and causes more civilian death. Reporter Dahr Jamial, in an article entitled "Living Under the Bombs" wrote: One of the least reported aspects of the U.S. occupation of Iraq is the oftentimes indiscriminate use of air power by the American military. The Western mainstream media has generally failed to attend to the F-16 warplanes dropping their payloads of 500, 1,000, and 2,000-pound bombs on Iraqi cities -– or to the results of these attacks. While some of the bombs and missiles fall on resistance fighters, the majority of the casualties are civilian –- mothers, children, the elderly, and other unarmed civilians. The sheer power of the bombs and the destruction left in their wake not only destroys homes, livelihoods, and neighborhoods, but also incentivizes mass refugee flows within the country from civilians fleeing war zones. Refugees are just accidents waiting to happen if the experiences in central African and Palestine have any merit. Dahar Jamil returns to the subject of the civilian cost of bombing in "An Increasingly Aerial Occupation". Hersh records the random and arbitrary nature of this terror: The insurgency operates mainly in crowded urban areas, and Air Force warplanes rely on sophisticated, laser-guided bombs to avoid civilian casualties. These bombs home in on targets that must be “painted,” or illuminated, by laser beams directed by ground units. “The pilot doesn’t identify the target as seen in the pre-brief”—the instructions provided before takeoff—a former high-level intelligence official told me. “The guy with the laser is the targeteer. Not the pilot. Often you get a ‘hot-read’ ”—from a military unit on the ground—“and you drop your bombs with no communication with the guys on the ground. You don’t want to break radio silence. The people on the ground are calling in targets that the pilots can’t verify.” He added, “And we’re going to turn this process over to the Iraqis?” Protesters against the war advance three main arguments in their opposition to the war: (a) too many Americans are dying, (b) too many Iraqis are dying, or (c) we've created a worse mess with intervention that is exacerbated by continued American presence. Drawing down the level of American troops and relying more on Iraqi security forces solves the first problem at the expense of the second. America's reliance on airpower, in this war and many of the wars it has fought in the past, is not a form of strength and superiority when unaccompanied by land forces; rather, it is a tacit concession that our grand strategy has exceeded our political will. The civilians in the war zone suffer as a result. Saturday, January 14, 2006

Extending New Year's I am having part two of my New Year's vacation. Some friends came over from Philly on Wednesday; our late nights and long days prevented blogging. More to come next week as I settle down again. Tuesday, January 10, 2006

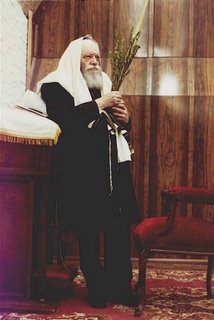

Why Chabad Matters for Non-Jews Hands down the best discovery of my junior and senior years was Chabad, complete with Rabbi Moshe Gray and his wife, Chani. I had every reason to be uncomfortable in a stereotypical Lubavitch household: being liberal, Protestant, black, and a recovering Zionist. Instead of a nightmare, I found one of most rewarding intellectual, spiritual, and social communities at Dartmouth. I. My Disaffected Dartmouth Days God, and the remembered and experienced stories of the power of the divine made manifest in human affairs, are very important for me. While I would have once described myself as theologically conservative because I believe that the Resurrection actually happened and that Christ was fully God and human, I now describe myself as a liberation theologist. That label simply means that theology, and the idea and concept of divine are more than conceptual artifices toward which and upon which we turn our mind's eye to contemplate in the stillness and the silence. Rather, to be saved by God is to be saved from this world for the purpose of furthering the divine imperative: "Love God with thy whole heart, mind, and body, and love thy neighbor as thyself." Salvation requires both a theological commitment to the sovereignty of God in our personal lives as well as the lived experience of caring for the widow, the orphan, and the oppressed. These theological beliefs have caused me to drift from the institution of a church who, as a social organization, contributes actively to the oppression and degradation of many of God's children. The most despicable face of my coreligionists appears in their politicized disavowal of the humanity of homosexuals (as if timeless divinely revealed truths would nicely correspond to the politicized differences of today), and, is also evidenced in the racist, classist, and sexist ideologies supported and encouraged by the same church. Jesus remarked "Be of good cheer because I have overcome the world." Heidegger, I think, provides the best meaning of what Christ might have meant by world. For Hedeigger, world was Daesein in which human beings interact by finding sites of meaning and significance in the being of others and in their crafted surroundings. Using this meaning of world, Christ calls us to rejoice for He has overcome the otherwise steel trap of repetitive human relations to create new possibilities for existence. The modern church, on the other hand, lacks both cheer and the overcoming of the world; instead, it grimly fights a hopeless struggle to codify the conditions of being-in-the-world to the advantage of those in the highest social positions at the expense of those who already suffer. The Dartmouth Christian community has not overcome its world--being at Dartmouth--and, as such, reproduce the pernicious, peculiar representations, hierarchies, and ideologies of that world. Whereas in the larger culture homosexuality is the politicized issue preventing the church from its overcoming of being-in-the-world, segregation tethers Dartmouth religionists. Segregation is rampant at Dartmouth on all lines save for gender. The rich segregate themselves, the whites segregate themselves, the gays segregate themselves (though to a much lesser extent), and the athletes segregate themselves. Unwelcome and disapproving glances greet those Dartmouth students who would dare to mix it up, and, frequently, the closest three friends of any given non-minority at Dartmouth are of the same race, class, and sexual orientation (as far as they know) of the person in question. The self-segregation of the whites and athletes, however, is even more pernicious than the active discrimination of the 1970s; the self-segregation cloaks overt and ostentation displays of white solidarity, save for when a hyper-concern to issues of race and affirmative action manifest in student discussions, and leads to this silly idea that every students stands alone for him- or herself in a world of heavily policed speech. These notions are comical because degrading suspicions turned onto minority and female sources of support (like Women in Science or Cutter-Shabbazz) and the frequent recourse that many minorities are admitted by affirmative action due to the lower SAT scores (an unfounded assumption)suggest that speech codes don't really exist. Moreover, we know that no Dartmouth student is "alone" in any meaningful sense of the word. Observing the long umbilical cords, the discrete transfer of monies, and the phone calls of support are not difficult. Even in situations where the Dartmouth student might be homeless or incredibly poor, financial aid and the supporting of loving friends more than compensates the lack of familial support. II. Chabadic Redemption Into this misery, Chabad was a breath of fresh air. Many liberal professors would find it hard to believe that a religious organization better embodied the best of American culture than many of their propagandistic sermonizing on the plights of minorities and American injustices. However, despite all the social engineering attempts to the contrary, the campus remained bitterly balkanized. Unlike campus, Chabad never felt segregated, and privileged no social position over any other. It seems odd that an organization designed to reclaim the Jews who were leaving their faith would feel so welcoming to someone who ostensibly had nothing in common with the organization. Besides being non-segregated and being welcoming in ways that the non-coed fraternities or Food Court could never be, Chabad was one of the few intellectually honest places on campus. All reasoned and considered views are welcome at Chabad; the Rabbi enjoys learning and listening to the lives of others and soon his guests come to exemplify those virtues also. This listening and learning, however, does not occur in isolation. Rabbi Gray never privileges the conceit of science--that science embodies all knowledge--and does not buy into the atomized model of human existence. He is always fully clear that his life has meaning through and because of (in no particular order) Chabad, Chani, the Rebbe, Judaism, Dartmouth, and the Jewish people. Why does the home of Rabbi and Chani Gray exude such warmth and acceptance? Why are is household shielded from the pernicious ideologies of the outside? The answer is remarkably simple and complex at the same time: the Rebbe.  It's hard to do justice to the life of the Rebbe. However, just a few minutes with Rabbi Gray are sufficient to see that the Rebbe, whom I believe he personally met, inspired this son of Judah to embark on a life of faith. The Rabbi always jokingly aggrandizes himself--he's his own best propagandist--but is always humble when speaking of the world and the life of the Rebbe. Though he would never admit it, the Rabbi is more like the Rebbe every time I meet him. It is clear that his encounter with the Rebbe encouraged him to devote his life to the existential pursuit of ethical and spiritual modes of life, and to helping everyone take up of the challenge of ethical living. The writings and the actions of the Rebbe, as well as the thoughts and life of Rabbi Gray, have as their starting point the concern of the Jews as a spiritual people. The Rebbe and the Rabbi always want to do right by the Jewish people above all else, and both sought the face of God for that right thing to do. Many would condemn this hyper-sensitivity to the fates of the Jewish people as ethnocentric and parochial. However, the ancient promise between God and Abraham holds true today "I will bless those that bless you and curse those that curse you." Again, "from Judah shall come salvation from the whole world." The Rebbe and the Rabbi begin with the Jewish people, but they do not end there. Their concern for the promises of God as revealed through the Jewish people allow them to occupy the universal speaking position where they seek the Torah-for-the-sake-of-heaven and can advise, love, and encourage all persons. The ironic and bitter lesson of the Rebbe's life and the Chabadic mission is that the divine blessing specifically stop flowing when the Jewish people forsake themselves. If the Rabbi were to forsake the Jewish people as his principle source of concern, he would lose his capacity for care for non-Jews. Thus, somemthing as universal of agape-love begins as parochial, particular concern contrary to the cosmopolitans and liberal political theorists. Like Christ, Jews must overcome the world and become the chosen people once again to remind everyone else to be is to be in the presence of God and of the significant others: friends and family. "Out of Egypt I have called my son" the prophet remarked of God's people; out of Dartmouth, the Rebbe and the Rabbi have called to all those who would listen. It was the Rabbi, Chani, Mendel, and Chabad who taught me that salvation begins after the overcoming. I have class potentially all day today so come back later this evening for today's post "Why Chabad Matters to Non-Jews." Monday, January 09, 2006