The Dartmouth Observer |

|

|

Commentary on politics, history, culture, and literature by two Dartmouth graduates

WHO WE ARE Chien Wen Kung graduated from Dartmouth College in 2004 and majored in History and English. He is currently a civil servant in Singapore. Someday, he hopes to pursue a PhD in History. John Stevenson graduated from Dartmouth College in 2005 with a BA in Government and War and Peace Studies. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. He hopes to pursue a career in teaching and research. BLOGS/WEBSITES WE READ The American Scene Armavirumque Arts & Letters Daily Agenda Gap Stephen Bainbridge Jack Balkin Becker and Posner Belgravia Dispatch Belmont Club Black Prof Brown Daily Squeal Stuart Buck Cliopatria The Corner Crescat Sententia Crooked Timber Demosthenes Daniel Drezner Dartlog Free Dartmouth Galley Slaves Victor Davis Hanson Hit and Run Instapundit James Joyner Mickey Kaus Martin Kramer The Little Green Blog Left2Right Lenin's Tomb Joe Malchow Josh Marshall Erin O'Connor OxBlog Pejman Yousefzadeh Bradford Plumer Political Theory Daily Info Virginia Postrel Andrew Samwick Right Reason Andrew Seal Roger L. Simon Andrew Sullivan Supreme Court Blog Tapped Tech Central Station Michael Totten UChicago Law Faculty Blog The Valve Vodkapundit Volokh Conspiracy Washington Monthly Winds of Change Matthew Yglesias ARCHIVES BOOKS WE'RE READING CW's Books John's Books STUFF Site Feed |

Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Country Before Party Prime Minister Arik Sharon, known for his legendary gambles as a general, left his a political party he found, the Likud, to make a new one, Kadima (forward). But's that not the real news. Former Prime Minister and vice premier Shimon Peres has left the Labor Party, a party he's served as head of and prime minister of at least three times, to join Sharon's party. This might not necessarily be a good a thing for Israeli politics and the peace process for four reasons. One, there has been a Washington consensus around the Israeli question since Sharon formed a coalition unity Labor-Likud government. There are generally three splits in the political elite on who to support in Israel. (It is a virtually unanimously held opinion, outside the CIA and State Department, that American support for Israel should go unchallenged.) Hardliners in America prefer Netanyahu, who had a portfolio in the government until trying to challenge Ariel Sharon for power. The hardliners, however, remained appeased due to the formidable Likud presence in the Sharon government. Centrist Republicans and Democrats prefer Peres, the Olso peace process, and the Labor party. As long as they were in the coalition government, there was no reason to criticize the actions of the government. Finally, there were the realists, who supported the Sharon disengagement plan and the Road Map. UPI offers that the breaking of this consensus will rock Washington. By abandoning the Likud party that he helped to found 32 years ago and forming a new third party, Kadima, in the center of Israel politics, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon has broken the consensus that held American politicians of both parties, from President George W. Bush to Sen. Hillary Clinton, D-N.Y., loyal to the Sharon government. Even if they had qualms about Sharon, Democrats like Clinton were reassured by the presence of veteran Labor Party leader Shimon Peres in the governing coalition alongside Sharon. When the Labor party withdrew from the government after Amir Peretz became head of Labor, there was a real potential that the Israeli electorate and American elites would rethink our relationship to the failed pursuit of peace in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The UPI believes that Sharon's move will allow the EU to exercise greater flexibility. Shimon Peres' move to join Kadima and support Sharon changes all that. Two, Peres' support not only complicates a renewed debate over the peace process within Israeli and American politics, it is also draws the upper middle class (generally Ashkenazim Jews), who would likely support Peres, against the poorer Sephardi Jews who usually vote for Likud but to whom Peretz is appealing for new voters in the Labor party. As the UPI details, Peretz is using his Sephardic credentials to bring those voters to him: "Peretz is a Sephardi Jew from a North African background, and thus able to appeal to that crucial voting block of Sephardi Jews, many of them working class, who have been critical to Likud's support. And by stressing social spending, jobs and wages, Peretz is trying to change the terms of Israel's political discourse away from security (where Sharon is so powerful) to economics (where Sharon and Netanyahu are very vulnerable)." If two problematic cleavages in Israel--the ethnic rivalries of the Ashkenazim, the Sephardi, and the Russian Jews as well as the class rivalries of the semi-socialist Israeli state--codify and crystallize into party affiliation, the Israeli political sphere could become even more fractured than it already is. Three, Peres' departure takes those upper middle class votes from from the Labor party, which has increasingly started its outreach to Arab-Israelis. The extent to which Labor becomes a repository of rage against an Ashkenazim-dominated state is the extent to which Israeli discourse is going to take a dramatic turn, for the worst. Four, and finally, Peres and Sharon's decision represent a consensus within the founding generation about their mistrust about the motives and abilities of the younger Israeli leaders. The two men [Sharon and Peres] are both part of Israel's "founding generation" and they've been good friends for decades. Both Peres, who is 82, and Sharon, who is 77, have little faith in the new generation of Israeli leaders. They believe together they can secure some kind of agreement with Palestinians over the establishment of two states. This is all to say: Peres is Sharon's blessing--and problem right now. Even though Peres suggested that he was putting country before party, many, on the left and right, have interpreted this as just another political move to guarantee his continued power. Tuesday, November 29, 2005

The Holy See takes a New Look To Gay Catholics: In case you hadn't noticed, your church just flushed any remaining dignity you had down the toilet. Not only are you sinners--even some Protestant churches, I'm afraid agree with that statement--but you can't even become priests. A life of celibacy isn't enough to prevent you from undermining the "God-given" (read: politically-fabricated) values of the Church in Rome. You are only OK if you "discovers his homosexuality after having been ordained." So it's best, in the eyes of the Holy See, if you save your sexual experimentation until after ordination. To Bi-curious Catholics: Your life isn't as worse as the gays; for that rejoice. If your homosexual experience has been "transitory"--all you two beer queers out there--fear not. If you would simply end your curiosity and get back on the straight and narrow path--emphasis I'm presuming on straight because the road to hell is not only wide, it's gay too--you'll be saved again. "What must I do to be saved?" "Stop being gay and come to church." To the American Catholic Church: Please forget all this pretense about the church being universal and united under Rome. After all, Catholic doesn't mean universal any more; we just another denomination like the Mormons or the Protestants. And the Reformation was so dreadfully long ago; unity was overrated them and is overrated now. It's most important that you just keep coming to church and leave the politics to the bishops. Given this, I would like to inform you the head bishop of America, William S. Skylstad who is also president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, is as openly supportive of Rome as possible given his disagreement with the Church. His spin on the document? "Gay-inclined are cut some slack." Skylstad, 71, who has led the Diocese of Spokane since 1990 and has been a bishop since 1977, said the question of whether "homosexually inclined men" can be good priests depends on how they live and what they teach. Translation: It's important that you remain committed to being celibate priests not having sex while continuing to affirm the centrality of fertile heterosexual copulation. What does all this "slack" mean? The rope around your neck chafes more than it chokes. Skylstad urges church leaders to have a "comprehensive discussion" about the affective, or emotional, maturity of every candidate for the priesthood. Oh, and in case you were wondering about what "deep-seated [homosexual] tendencies meant: "the prohibition against men with "deep-seated tendencies" means a person actively looking at pornography or visiting gay bars would not be acceptable in the priesthood, but simply having an attraction to men would be. supporting gay culture means that a seminarian is "so concerned with homosexual issues that he cannot sincerely represent the church's teaching on sexuality." Monday, November 28, 2005

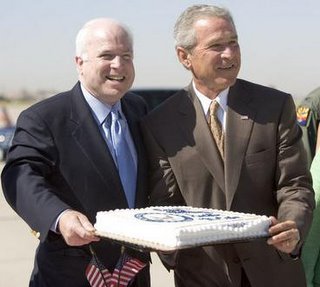

Hating Bush, Fisking McCain After the failures of the Bush Administration, conservatives are lining up for a home-run hero; they don't want any more false conservatives. Bush, who was thought to have arguably remade the Republican Party until the Miers revolt, has betrayed "conservatism" on every account, particularly when it comes to fiscal issues. For the more snobbish and intellectually-inclined conservatives, references to Edmund Burke or Russel Kirk are obligatory. Jeffery Hart, professor emeritus of English at Dartmouth, presents an excellent example "conservative" anti-Bush vitriol in his latest op/ed entitled, "George W. Bush, Bogus conservative." George W. Bush is not a conservative, but a right-wing ideologue who steers by abstractions in both foreign and domestic policy. Inevitably a perilous gap opens between his abstractions and concrete realities. Hart's analysis was precious, right down to the "wheeee" at the end of a paragraph about Tom Delay. What is most amusing, and instructive about this retrospective, ad hoc conservatism is that Locke doesn't get to make the cut whereas FDR does. When did FDR become a conservative? I think another "wheeee" is in order. More importantly, when was Locke kicked out of the conservative pantheon of saints? Stephen Bainbridge, law professor, whom I will upbraid in a moment, quotes Russell Kirk who wrote, "... the true conservative does stoutly defend private property and a free economy, both for their own sake and because these are means to great ends." Locke, particularly as he was invoked by Robert Nozick in Anarchy, State, and Utopia, the bible of libertarian conservatism, was one of the first theorists to defend the right to property at almost all costs. In fact, for Locke, the beginning of liberty was the ability to input value into property. Locke so thoroughly believed in the right of property that he even defended British colonialism in America on the contention that British settlers would add value to the land, and that this right of property transcended any government's ability to interdict or interfere. Locke was definitely a conservative. Conservative fury over Bush, moreover, has also led to the beginnings of the campaigns pre-2008 against Senator John McCain. Stephen Bainbridge on that point wrote: I get all schizo when I think about John McCain. I admire his life story and I think his "national greatness" version of conservatism is an interesting take on the problems of the day. But there's so much about him that drives me nuts. Ultimately, I can't imagine supporting him in light of: Stephen Moore's piece can be summed up in this paragraph: [McCain] views himself, I believe, as a kind of modern-day Robin Hood, a defender of the downtrodden and tormentor of the bullying special interests, which is endearing and unquestionably a big part of his broad political appeal, but often leads to populist and parasitic economic policy conclusions like higher taxes on the rich and attacks on "huge oil profits." He wants to be the caped crusader against corruption. The buzzword for the McCain Straight Talk Express in 2008 will be reform: "I want to reform education, reform Medicare and Social Security, reform lobbying and campaigns. Reform immigration. Reform. Reform. Reform." Bainbridge then, after trotting out a quote by Russel Kirk, concludes that McCain's reformist tendencies aren't truly conservative--I'm wondering how that squares with his statement at the beginning of post "his "national greatness" version of conservatism is an interesting"--and that ultimately we should avoid McCain if we want a "real" conservative in the White House. Now McCain's conservatism, and I'll prove that it's conservative in another post some other time, is summed up his view about immigration: "America must remain a beacon of hope and opportunity. The most wonderful thing about our country is that this is the one place in the world that anyone--through ambition and hard work--can get as far as their ambition will take them." All of the evils Bainbridge attributes to McCain come from the senator's basic willingness to prevent the uncaring titans of capitalism and government from choking out the ambition of drive of individual Americans. And it is this ability of individuals to make a fate and a living for themselves that makes America great in the McCain vision. For McCain, the malefactors of great wealth, a ballooning national deficit, and a badly managed war in Iraq all limit the ability of this country to be great. And I can't see why conservatives should disagree with that. Friday, November 25, 2005

Nuremberg's Continuing Importance The Nuremberg trials of the Nazis after World War Two are arguably the bedrocks of international law. The Nation memorialized Telford Taylor, a Nuremberg prosecutor who died in 1998, as the man to whom the "human rights movement owes much of its legal foundation. . . [Taylor's work in] Nuremberg gave legitimacy to the concept that the world had something to say about how governments treat their own citizens. In 1950 the United Nations codified Nuremberg's most important statements into seven Nuremberg Principles, which have since been adopted by the legal systems of almost every major nation." Wikipedia suggests the conclusion of Nuremberg led to four important conventions now considered sacrosanct in international law: (1) The Genocide Convention, 1948, (2) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, (3) The Convention on the Abolition of the Statute of Limitations on War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, 1968, and (4) The Geneva Convention on the Laws and Customs of War, 1949; its supplementary protocols, 1977. Eric Posner, a professor of law at the University of Chicago, criticizes the Nazi war crimes tribunal by suggesting that the judgements of Nuremberg are not law in any meaningful sense. If Posner is correct, then all of the conventions, treaties, and norms that declare Nuremberg as their inspiration are legally smoke and mirrors. Let us begin with Posner's comments on Nuremberg. After that, I shall briefly point out some flaws in Posner's critique and offer why Nuremberg is still important. Posner's observations crystallize around three points. One, Nuremberg was a legal act in only the thinnest sense. The "legal" basis of Nuremberg stemmed directly from a policy paper, the London Charter, and was nothing more than a "sensible, politically expedient decision [disguised] as a moral judgment." Any enforcement of this policy paper would be political and not truly legal. Posner himself develops that point most succinctly: "Involvement of lawyers and judges does not convert an administrative procedure into a legal procedure, much less convert a political act into a tribute to Reason, at least not in any morally important sense." Two, contrary to Jackson's assertions, the Allies did not stay hand of vengeance in any meaningful way. By the time the war ended, the Soviets, the British, and the Americans had bombed thousands of German civilians and massacred millions of German troops. Those Germans who were fortunate enough to survive watched the victors divide their country and rape the women while the neighboring countries purged their territories of Germans. There was indeed vengeance, Posner argues, and the Germans felt it. Three, Posner continues, Nuremberg tried the leaders as symbols of Nazi criminality and forced them to give account and take responsibility for the atrocities they caused. The allies made no attempt to try, detain, arrest, and indict all those responsible for the war and for implementing the dictates of the National Socialist party--indeed they could not if they wanted Germany to continue as viable nation. Pragmatism demanded that "thousands of culpable nationalists and militarists were permitted to resume ordinary life." Trying the symbols of the failed regime, Posner concludes, "might have been sensible from an administrative perspective, from a public relations perspective...[or even] politically shrewd under difficult circumstances. But it was not a great moral victory, much less a vindication of the rule of law." In fact, the limitations and expediency of the entire Nuremberg process, in that "it did not establish an effective international rule of law that would constrain states over the next half century," suggests that its celebration as "one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason" is unwarranted. Gary Bass's, a professor of political science at Princeton, work on Nuremberg is useful for contextualizing Posner's point about the postwar situation. He wrote a book entitled, appropriately enough "Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals", and came here to the University of Chicago, at Eric Posner and Eugene Kontorovich's invitation to present his work at the International Law workshop. Bass maintains that war crimes tribunals, of which Nuremberg was not the first or the last, are messy affairs, especially "if one wants to get rid of undesirables; using the trappings of a domestic courtroom is a distinctly awkward way to do it. Sustaining a tribunal means surrendering control of the outcome to a set of unwieldy rules designed for other occasions, and to a group of rule-obsessed lawyers. These lawyers have a way of washing their hands of responsibility for the political consequences of their own legal proceedings." Postwar diplomacy is messy and legal rules and trappings don't help. So why use war crimes tribunals? Bass develops the answer at length: The core argument...is that some leaders do so because they, and their countries, are in the grip of a principled idea....Some decision makers believe that it is right for war criminals to be put on trial—a belief that I will call, for brevity's sake, legalism. In fact, even though Winston Churchill wanted to shoot all the Nazis after the war, President Roosevelt right before the Yalta conference, had become persuaded by the need for a case to document the crimes of the Nazi regime. Stalin agreed with Churchill's basic sentiment of shooting Nazi leaders but quipped, "In the Soviet Union, we never execute anyone without a trial." Churchill agreed saying, "Of course, of course. We should give them a trial first." All three leaders issued a statement in Yalta in February, 1945 favoring some sort of judicial process for captured enemy leaders. Stalin and Churchill's support of the trials, however, were only intended as cover for doing what they wanted to do anytime: stick it to the Germans and the Nazis for their third major war in seventy years. The British and American judges, however, saw the point differently, and were committed to a fair process. Justice Robert Jackson conceded that although whether to hold trials or not was a political question. "It's a political decision as to whether you should execute these people without trial, release them without trial, or try them and decide at the end of the trial what to do. That decision was made by the President, and I was asked to run the legal end of the prosecution", once the politicians had decided in favor of trials, the rule of law should reign supreme. Jackson, in his discussion with negotiators from the other nations, further stipulated: "What we propose is to punish acts which have been regarded as criminal since the time of Cain and have been so written in every civilized code." This might have, and indeed did, lead to some leaders being acquitted under the rules established for the proceedings. In fact, as Bass pointed out in the workshop--between making fun of my purple hat--the Soviet judges, accustomed to rubber-stamping the political decisions of the Communist party, were upset when their British and American colleagues voted to acquit some Nazi leaders. For the Americans and the British, the tribunals represented the postwar moment where, through legal proceedings and the rule of law, the vengeance expected on the battlefields and in the prison camp was bracketed and sublated into the rules-governed adversarial process of legal adjudication. The Soviets, on the other hand, saw trials, massacres, and shootings as equal opportunity tools of a victor's justice of vengeance. Leaders were tried before they are shot--the judicial legitimates the political and the violent--;the soldiers and POWs were executed and deported; the women, at the mercy of the soldiers, were raped to atone for the German crimes of aggression; and the industry and workers of E. Germany, where the Soviets reigned supreme, were shipped back to the homeland to aid in the cause of socialism. Posner pointed out that some militarists went back into civilian life because we couldn't catch them all. That was only really true in W. Germany; in the east, the Communists, after spending years in the prison and death camps, sought to purge Germany of the fascist militarism, and largely did through the wholesale slaughter and internment of a good portion of the adult population. Does it matter that even in W. Germany, Nuremberg wasn't really law in the way that American domestic law is law? Not really. That Nuremberg took the form of law and legal processes was important--that it was a vindication of the rule of law was less central to the lessons of Nuremberg. Posner is disappointed because Nuremberg was essentially legal enforcement of a policy decision. But the strength of Nuremberg is not the fact that it's good law--Posner's right on that point--but that it underscored the importance of (1) using lawyers, judges, and legal processes to carry out politically sensitive jobs and (2) time-bounded institutions as means of resolving delicate questions. First, because of the professional importance of following rules and procedures, and, more importantly, creating legitimacy for their actions, legal processes and languages have become important ways of cooling down hot potatoes. What do we do with Saddam, Milosevic, and Pinochet? We could shoot them; it's probably more than they deserve. No, instead, the United States wants to try them and demonstrate, plainly for all to see, that like Eichmann, these men are not just criminally culpable, they represent a type of evil in the international system that can only be contained by leaders who submit their authority to the rule of law. Like Eichmann, Napoleon, or any of the others leaders tried before tribunals, Pinochet, Milosevic, and Hussein "never aspired to be villains. Rather, they over-identified with an ideological cause and suffered from a lack of imagination or empathy: they couldn't fully appreciate the human consequences of their career-motivated decisions." Even American presidents have done atrocious things in the name of power politics--Bush I watched the Kurds die and Nixon destroyed many countries in South Asia--but ultimately the rule of law, in this case elections and threat of impeachment--removed the cancerous sores from the American polity. Second, these temporally specific institutions, established to do one job, grant states and non-state actors a place where they can create political frameworks designed to deal with a specific situations. This political understandings often create convergence around new normative frameworks--like the principle of distinction or the concept of genocide after Nuremberg--that give state leaders rhetorical tools to legitimate their actions and non-state actors normative tools to mobilize support and criticize states. Legal process are the best forms of institutional legitimation and power to accomplish the resolution of delicate political questions. Thursday, November 24, 2005

Autumnal Beauty and Thanksgiving I hope that everyone is having a splendid Thanksgiving. In light of the day, I wanted to link to something quite beautiful. Enjoy.  Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Re-evaluating the Panthers: Was King right and the Black Power movement wrong? One of the first things you learn in Civil Rights history is that Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King is the icon of inclusion, tolerance, and the fight for justice. Teachers and historians alike ascribe to his message-- that discrimination and racism are inconsistent with American ideals--the adjective "universal." By that term they mean that King's message was a message for all people in every social position to resist racism and discrimination everywhere they found it. However, we also know that there was at least another message broadcast concurrently with King's: the message of black power. The Black power movement, unfortunately, always lives in the shadow of King's movement; lacking the "wide appeal" that King's movement had, politicians and pedagogues today encourage us to remember the black power movement as the failed illegitimate side of the struggle for civil rights. Thus, the black power movement, ironically, is marginalized in the civil rights history and discourse. There are two main ways analysts dismiss the movement. The first method is to cast black power as a violent response to the death of King. The civil rights movement, in this story, fragmented without King's unifying touch, and became divided along class and racial lines within and outside the black community. The second way historians remove black power from the scene is to remind audiences of its "particularity." By using this word, analysts distinguish the specificity of black power from the generalness of civil rights. King's movement then becomes the re-presentation of justice for all and malice toward none whereas black power is simply more discrimination from one group to another rather than a break from the cycle. This dichotomy--of the general and the specific--allows the historian to castigate black power's ideology while supposedly continuing the tradition of civil rights. King is everything that black power was not. Is this the way we want to remember black power: as a failed, illegitimate, twisted shadow created in and by King's light? Surely not; remembering the history in this way prevents us from understanding the motivations of both movements and obscures the hierarchies of race and raced difference that both movements struggled to overturn.  Black power was about black people. It was uncomfortably militant, irredeemably particular, and dominated by young people who wanted revenge for the wrongs that they believed society had heaped upon them. The character of the movement was largely due to the demographic from which black power drew its earliest support: young black men. Whereas King's movement operated from the social position of the black elite with the support of many Protestant churches and Northern white liberals, the black power movement drew together isolated individuals outside of an institutionalized context into a paramilitary organization designed to fight the oppression of blacks. The youth were not only disenfrachised and disaffected, but they were worldless. At times the oppression seemed so thick and all-encompassing that each person believed that it just him alone against the world; black power aggregated those lives of separate resistance into a cohesive movement. The militancy of the movement scared away potential supporters--then as well as now. King's movement did enjoy larger passive support than the black power movement, especially when it was about southern racism. The southern states, with their redneck culture, have always been the perfect villain for the democratic mind. Southern racism was unapologetically discriminatory; it was as crude as it was callous. The yearning for black power, particularly as manifested in the Black Panther party, tackled racism in the North and West as opposed to the South, starting first in California. The party criticized American racism as a feature endemic to the American institutions of governance and capital; blacks were oppressed not only due to the racist culture of the United States, but also due to the systems of distribution, legitimation, and rule. Unsurprisingly, the Northerners were less willing to sign on to a project that suggest the whole of American society was flawed, a fact that King himself discovered when he turned from civil rights to jobs for the poor. Nevertheless, like King, black power was never exclusively about the lives of blacks, just primarily about them. The slogan of the Panthers was "all power to the people." They actively encouraged all blacks, minorities, and workers to take up arms against the government and the capitalistic system. Though their message was largely about black people--they wanted to talk about the same subjects the racists found so fascinating--it was for all oppressed. They didn't want to live harmoniously in a society whose very existence required the degradation of some for the enrichment of others. The logic of capitalism, for them, was the logic of slavery: one man's work became another man's dollar. (Women were largely outside of the story.) The history of black power, then, should not be remembered as a call of blacks against whites, but as a call to democracy against capitalism. If King believed that the genuine expression of democratic equality militated against raced difference and the reproduction of racial ideologies, then the Panthers believed that democracy militated against capitalist exploitation. I want to conclude by listing the ten point program of the Black Panther party. 1. We Want Freedom. We Want Power To Determine The Destiny Of Our Black Community. In closing, I will say this: the platform of the Panthers is much less radical today than it was when it was first offered. The Panthers were clearly committed to a non-capitalist democratic system because they believed that a racist market society would not provide for the welfare of its poorest members. This intuition is a common one on the left in America today. The Panthers argued that an all-white jury would not provide justice to black defendants. The Supreme Court stipulated the same thing years ago. The Panthers maintained that police brutality was a problem for black communities. Rodney King made their observation a national question. The Panthers argued that people have a second amendment right to bear arms. So does the Republican party. The Panthers reminded us that education was the key to self-knowledge. Most lawmakers would endorse that statement. Lastly, in point ten, the Panthers quoted the opening statement of the Declaration of Independence to remind us that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. The Founders may have been proud. It seems that we are all Black Panthers now. No Post on Tuesday I am sorry for not posting something on Tuesday. For all you loyal fans--all three of us (ChienWen, Rabbi Gray, and me), I usually update after my workshop but yesterday I had an engagement on the North side. Since I could have predicted that it would prevent me from coming home before 2AM, I should have update before I left. However, that just means that Tuesday, I will post twice. One post will deal with the invasion of Iraq and the other post will gesture at some thoughts about the black power movement. For all of you who will not be able to read for the rest of the week due to family engagement, I wish you all a wonderful Thanksgiving. I will post on both Thursday and Friday, and, as usual take the weekend off. Thank all you readers; leave a comment and tell a friend about the Observer. Monday, November 21, 2005

No Civilians Left?: Fighting Wars Today Child soldiers, some of whom are no older than six, are to be found in three quarters of the world's current fifty or so conflicts. In Sierra Leone's Revolutionary United Front (RUF), 80 percent of the fighters were aged between seven and fourteen. Twenty thousand children are reported to have served in Liberia's protracted civil wars, and there were many children among Rwanda's génocidaires. As if to make their use more palatable, many of these children were given childlike names. The Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka had a Baby Brigade and called their girl soldiers "Birds of Freedom"; there were "Little Bells" and "Little Bees" in Colombia and "Brave Sprouts" in Myanmar. Saddam Hussein called his child warriors "Lion Cubs."Are there any civilians left in the brutal wars of today? A chief principled assumption about conflict today is that harming civilians is bad and wrong. In the technical lexicon, this is known as the "principle of distinction." Whenever large numbers of civilians are killed on purpose, we use terms like "murder" and "massacre" to connote our outrage. For example, we don't refer to Lt. Kelley of Vietnam's action as "The Unhappy Incident of Mai Lai", but rather as "The Mai Lai Massacre." Even when civilians death are acceptable, as in the doctrine of collateral damage, their never ok; we still express shock that any civilians have to die at all. This chief assumption, though, faces one major flaw-- a flaw that becomes obvious the moment one is on a battlefield or knows someone who has been--the principle of distinction implies or assumes that a soldier can tell a civilian from a combatant when his or her life is in danger, or when he or she is in the field. And as always in a time of war, it's never that easy and definitely never that simple. The New York Review of Books, from which I took that opening quote, describes the terrible landscape of warfare in some of the most war-torn societies: Rwanda, where neighbors hacked each other to death with machetes, happened soon after, and Srebrenica, where eight thousand Muslim men were led away under the eyes of UN peacekeepers and murdered, and Sierra Leone, in which villagers thought to be sympathetic to the government had their hands and arms chopped off by rebel troops. In this new kind of war, said Sommaruga, everyone and everything—babies, crops, livestock, houses, old people—had become fair game. Nothing is sacred; there are no distinctions only a need to survive. What makes it worse is that there are no civilians left in this landscape. Even children, the archetypal civilian, must take up arms to defend themselves, and the interests of their cruel masters. Dante's Inferno, with its boundaries and systemic orderliness, would be heaven compared to the world that some of these child soldiers live in. Who are these child soldiers, this "lost generation"? Demographers started talking about the "lost orphan generation," they were usually referring to the 1.8 million South Africans who had lost one or both parents to AIDS. Long before that, however, the term "lost" had been used to describe another group of children altogether, also from Africa: these were the "lost boys" of Sudan, so called after Peter Pan's orphans cast as children into the world of adults. These "lost boys" were the 3,800 young Sudanese chosen from among the survivors of the thousands who had been separated from their families in Sudan's long civil war between North and South, and who now, in the new century and amid considerable publicity, were being welcomed to new lives in the US.Kaplan's The Coming Anarchy, in a way, was a characterization of what life would be like after states collapsed. The national economy would revert to a quintessential, cruel, parody of feudalism: control of land and the power of the military would be the means of securing a livelihood in the literal sense of the word. What brought all this about, as Singer points out, is in part the emergence of warlords and rebel armies hastening to fill the void left by failing states, seeking control not so much of countries as of poppy and diamond fields, or of coltan mines, which provide a mineral needed for cell phones and laptops. But the use of children was also made possible by the lightness, availability, and cheapness of weapons, the rifles, grenades, mortars, and machine guns dumped in the wake of the end of the cold war. You no longer have to be rich or strong to carry a Kalashnikov: it weighs little more than a small dog and, in parts of Africa at least, costs about the same as a chicken. A handful of children today, it seems, has the equivalent firepower of an entire regiment of Napoleonic infantry.Surely, as citizens of the world's most powerful state, this is not the fate we should allow any human being to wallow in. The tragedy, however, do not stop at the child soldiers. The supposed innocence of children quick retreats in the face of such appalling circumstances. The second tragedy is that when children lose their childhood, the category of civilians disappears as a meaningful distinction. The loss of civilians, in an age of total war, means that there is no one keeping alive a social space into which one can repatriate. Without civilians, there is no civilization, no post-war world, no normalcy, no peace. Dissenting Opinions? Gay-friendly opinions on the Christian Right I was reading Christianity Today online a short time ago when I stumbled onto a link that contained a suprisingly interesting discussion. The article, entitled, Baylor Dismisses Gay Alumnus From Advisory Board, detailed the removal of a very active alumnus from the Baylor social scence. The article tells a story typical of good people who are betrayed by their Christian, supposed cosmopolitan, community due to a politicized difference: He graduated from Baylor University in 1983, with a degree in accounting, worked his way up in the business world, picking up a Harvard MBA, working with a venture capital firm, and running a technology company. In the last decade, he has personally given about $65,000 in gifts to Baylor, and he raised another $60,000 to endow a fund in honor of a business colleague and the colleague’s wife — the couple had met at Baylor. No one is, naturally, surpised that a conversative Baptist institutions is homophobic. Sadly, we have come to expect that an institution based primarily on an act and gift of love by it's founder, Jesus Christ, would subscribe to some of the most hateful behavior. What was interesting here were the comments on the article. The comments take directly to task the flawed logic of politicized difference masquerading as sound theology. This was a choice comment: Do you think Baylor has ever dismissed someone from their board for coveting the possessions of others? because that’s also an abomination. Deuteronomy 7:25 “thou shalt not covet the silver or the gold that is on them, nor take it unto thee, lest thou be snared therein; for it is an abomination to the LORD thy God.” This person was probably a social scientist: Shelia, The Bible is somewhat ambiguous about these issues, but, as we can see, not all religious institutions think the bible requires them to expel gay people – and some think that it requires them to provide them with health benefits ! Since it is impossible to get an objective reading of what constitutes the “correct” religion, I think that people should proudly declare that they don’t like gay people – even if they are discrete about it – and stop hiding behind a bible (which they selectively quote from). This person wins the apposite sound bite award: I suppose IF homosexuality were a sin, Christians at Baylor would have the inherent abiltiy to “Love the sinner and hate the sin.” Was dismissing Smith an act of love. I think not. So, homosexualiity, as matter of life and not choice, its “acceptable” to hate the person. Makes me wonder... What would Jesus REALLY do? He probably wouldn’t apply to Baylor and if he did, he’d probably be dismissed for not wearing trousers! My personal favorite: Sinners need not apply And of course, the one that goes for the gullet: No one’s “shocked” by the actions of Baylor University, Sheila—we’re appalled. Appalled at the hypocrisy; appalled at the self-righteousness; appalled at the startling lack of sophistication displayed by “liberal Christians,” “compassionate conservatives,” or what have you, in reading, interpreting, or applying their own scriptures. Notice how the bible is always “clear” only on issues that suit the conservative social agenda, but mysteriously unclear when it comes to interpreting those prohibitions that good Christians violate on a daily basis. Somehow gays and liberals are the only ones who need to be held accountable to scripture, while the administrators who make these decisions have managed to stay clear of “sin.” Please...sell me some beachfront property in Arizona while you’re at it! When good Christians start holding their own leaders (and themselves) accountable to the same standards that they apply to others, then maybe the rest of us will take such “principled” stands as the one Baylor has taken a little more seriously. Ask George Bush to step down, then tell me it’s okay to dismiss gay people from their well-earned positions in our schools, churches, and communities. Appalled is exactly right. Maybe there is hope for a counter-bigotry position to arise from within Christian communities. I could just be too optomistic though. Sunday, November 20, 2005

Kaplan on Kissinger I just finished another Kaplan book: The Coming Anarchy -- a collection of essays, all of them written before 9/11, on the state of the world following the Cold War. The essay that I'm singling out here is the one on Kissinger and his doctoral dissertation on Metternich and Castlereagh. In it, Kaplan argues that Nixon and Kissinger kept American troops in Vietnam for as long as they did so as to maintain the US's strategic position vis-a-vis China and the USSR. Kaplan cites a couple of American foreign policy successes such as Nixon's visits to China and the USSR in order to substantiate this thesis, but he also writes that "there is no way to prove or disprove connections between the Nixon administration's cold-bloodedness in Indochina and its ability to project power elsewhere, to America's obvious benefit." I'd be interested in your views on both Kaplan's original argument, and on his claim that it can't be proven or disproven. Friday, November 18, 2005

To the land of Oz I go I'll be overseas in Australia from Sunday evening to Wednesday evening. Alas, it's an official visit, so I can't say much about it. I hope to blog a little before I go, but no promises. Obsession: The Search for Women We Americans are obsessed with women; it is a national pastime. References to and insinuations about women are to be found in every magazine, television show, song, work of philosophy, journal, and newspaper. The appetites of our imaginations to know Woman and to understand Her seem to show no sign of abating nor of being satiated. We have colonized every part of Woman: her imagination, her body, her sex life, her gender, her difference, her clothing, her religion, her most sacred communions of love and giving. What we enjoy most about Woman is discussing Her relation to Herselves. In that vein, the project of feminism--making women equal partners in social discourses and liberating them from hierarchies of sex and sexed difference--is the social-mental climax of our obsession. Feminism is all about women; talking about feminism is just another excuse to talk about Woman and Her "authenticity", Her relationship to Herselves. It is with that idea in mind--that we are obsessed with Woman's authenticity--that I will seek to understand the articles and essays which follow. After suggesting why the quest for authenticity is a bad way to do feminism, I offer a critical re-orientation for feminist projects. The Columbia Spectator on 3 November 2005 ran an article entitled "Is Feminism Screwing Women? Or Are Women Screwing Feminism?" (Thanks to Rabbi Gray for this tip.)The title itself betrays the author's presupposition that women are uniquely the authors and targets of feminist inquiry. To the extent to which a feminist critique is a challenge to hierarchy, inequality, and sexed difference, it is also a relational proposition for both men and women. Feminism is, to be sure, the articulation and culmination of women claiming their humanity and personhood, but the claims to that humanity and that personhood are claims about belonging to a cosmopolitan group inclusive of all and exclusive of none, especially on grounds of sex. At the heart of this project are twin goals, both equiprimordial, of liberation and equality. Understanding the feminist project is crucial to understanding how women today relate to that project, and whether Woman is being true to Herselves. I take up here the challenge of answering the question "Is Feminism Screwing Women? Or Are Women Screwing Feminism?". In order to get at the question we need to know what feminism isn't, what feminism is, and who are women? Contrary to popular belief, feminism is not the sexual revolution. Harvey Mansfield a Harvard political philosophy professor made famous most recently by his tactic against grade inflation—giving students As on their transcripts and a separate grade they deserved—has been talking about nothing but feminism these days. His new book on manliness explores the boundaries of feminism, making the argument that there is nothing “liberating” about women trying to rack up sexual partners like guys. By playing “the men’s game,” women are just submitting to its restrictions. With Levy and Mansfield on my mind, it was impossible to see the various varieties of slut nurse, slut policewoman, slut angel, slut devil, and slut maid strutting around this Halloween and not ponder the question of feminism.The misunderstanding here comes from a conflation of the message of sexual liberation and the project of feminism. The aim of the sexual revolution was to cast aside cumbersome social mores and rules surrounding the public pursuit and acknowledgement of the act of sex. The goal of sexual liberation is the pursuit of the good "fuck" without any authority, secular or ecclesiastical, providing prohibitions on the path of pleasure. The sexual revolution was rooted in biological and psychological desire; it freed the individuals to get what they wanted without sympathy, remorse, or second thought, and, most importantly, to be able to talk about it the next day. The revolution was particularly helpful in bringing the sex lives of those who have them--and the pity for those who don't—into full public view, thus allowing sexual discourses to be medicalized as a regulation for the safety of the body. The author's conflation of the revolution of sex with the project of feminism is no where more apparent than in her/his description of a Chabad Jewess as "an orthodox woman, wife, and mother who covers not only her body out of modesty, but also her hair...[and] has been either pregnant or breast-feeding for the past seven years." He/she continues: "in a culture where some claim feminism means flashing your tits to drunken guys on spring break, certainly a[n] [orthodox] woman... is more than worth considering." Feminism is more than about getting off and getting wet. The project of feminism has to be more than the ability of females to fellate guys they hardly know, of two guys to make out in public, or of two lesbians to give each other a hand during an awful movie. Sex isn't politics and feminism was quite political. Karen, our Chabad Jewess, however, tell us a lot about what the project of feminism is. "I discover that she runs a 501(c)3 and is pursuing a master’s degree in psychology at Teacher’s College. To those who still turn their nose up at her way of life, she says, “If you say you’re a feminist and you are judging women like me, maybe you need to rethink your feminism." Karen's life, lived in accordance to religious authorities and as a head of a 501(c)3, demonstrates both the liberating and equalizing components of the feminist project. Feminism is liberating in the sense that it grants persons, especially women, the ability to speak and act in public fora without being constrained by their sex and social sexed difference. It is equalizing to the extent to which the hierarchies of sexed difference, and in particular the manipulation of those hierarchies to uphold male privilege and the enforcement female subordination, are challenged, exposed, and subverted. The feminism project is incomplete, however, because our society is still caught up over the issue of women. Whether in the mini-skirt or the veil, men and women in positions of power continue to want to regulate and prescribe actions for women so that they can signal their social position. When one listens to the "dance Hip-Hop" so popular these days, the rappers encourage the women to "shake their asses" to signal to "brothas" and other ladies their intents. Conservative Jewesses and religious Muslim women are under intense pressure to dress their part. Arrogant and/or diva/ ghetto fabulous thick women are derisively told by horny men to "act their weight" when these men's offers of sex are rebuffed and rejected. Liberal feminists froth over how religious women dress, encouraging the religionists to forsake their garbs to display female solidarity against oppression. Prurient men defend their right of free speech to pornographically depict women as sexual objects for heterosexual male fantasies; even if is free speech, the voice of the women in these videos are obscured by the penises in their mouths and vaginas, and the possessive, rough male hands on their heads. Feminist preoccupation with the right of abortion demonstrates just how co-opted the movement has become from its radical roots. I quote this passage from Washington Post to gesture briefly at a larger problem. One of the major issues facing Alito is where he stands on abortion. All you have to do is read his dissent in Planned Parenthood v. Casey to figure out where his feelings are. The case had to do with a requirement that a wife prove she had notified her husband that she intended to have an abortion. The Supreme Court sided with Planned Parenthood and overruled Alito.Is the main problem here that Nancy has to ask Horace's permission to get an abortion, or that Horace feels its ok to ignore Nancy for a game? Or maybe that ultimately Nancy is alone in the world when it comes to the issue of children and her pregnancy? If she has the baby, Horace will hate her; if she does not have the baby, she alone must make the decision to undergo the procedure. Feminism has a long way to go when the defense of Western aggression into the postcolonies is a defense of white men and women saving brown women from the brown men and their gods. Of all critical projects, feminism should know that military imperialism hardly ever creates conditions of equality. The fact that veil is still a site of struggle and contestation between legal-religious authorities, women of the postcolonies, western feminists, and western political leaders in France, in Turkey, in Germany, in Afghanistan, in Saudi Arabia, and numerous other countries means that feminism is incomplete. Feminism will be complete when it understands that targeting hierarchies of sexed difference means undermining all projects and philosophies that seek to define women as women and to confine them as such. This means exposing all hierarchies of difference--class, race, gender, and sexuality--and unmaking those hierarchies so that all can achieve their humanity. At least that is what I mean when I say that I am a feminist. Finances, Freedom, and Autonomy: Early Thought for the Day There will be another Friday update. Hopefully I will finish responding to at least one of the articles sent to me by Rabbi today. (The one about women I think.) I was reading the archives of my Livejournal and came across this thought-piece written on 15 March 2005 which I wanted to share with all of you: Who ever said that money can't solve all your problems? It was probably a rich or middle class person. The irony of our current market society is that people with money maintain that their money causes them so many problems whereas the less fortunate pine for less strict finances. God has blessed me greatly as an undergraduate by allowing me to go to Dartmouth. On the whole, the College is, monetarily speaking, very supportive and providing of my needs. The freedom of financial aid, combined with a host of outside scholarships, has basically allowed me to escape the tragedy of my family situation.I wanted to share. Thursday, November 17, 2005

Public Scrutiny of Poverty David Shipler, a minor celebrity at Dartmouth College, provokingly wrote: "[W]hat government fails to do is usually not defined as news. But it should be, for neglect is a form of policy, too. When government ignores a problem, the problem festers and usually fades into the shadows of coverage until a Hurricane Katrina ravages New Orleans or a riot tears through South-Central Los Angeles.... Katrina, then, has offered an opportunity for the press to rethink its inattention to a national disgrace. No problem gets cured unless it is first turned out into the sunlight." Race and poverty hadn't always been so jolting the nation, Shipler argued, because there was a time when newspapers regularly featured stories on such issues. What had been different in the past was government action; when the government did anything involving the issue of poverty--from Lyndon Johnson's the Great Society to the 1996 welfare reform--the media centers covered the effects of those government policies. However, as the government did less work on those areas, or, as the government's services to those areas became routinized over time, media coverage dropped. Shipler goes on to suggest that the administration's mismanagement of the response the Hurricane Katrina re-centered the question of poverty and race in the public consciousness, and, for a time, put the issue back into the news. Nevertheless, just because Americans were paying attention to racial inequality for the first time since the 1990s, doesn't mean that everyone was suprised. In fact, Shipler forwards the proposition that those living and working among the impoverished were certainly not surprised. The deep suspicions of authority among impoverished African Americans — the distrust of police, politicians, and even rescue workers — would not have puzzled anyone who has worked on racial issues, and it should not have amazed a literate public educated by solid reporting on racial tensions and injustices. Surely it was no revelation to those who work in nonprofit antipoverty agencies that many of the poor lived in neighborhoods most vulnerable to flooding but could not evacuate because they had no car, no place to go, no credit card for a motel, or — even if they owned vehicles — too little money for a tank of gas. I take Shipler's point and think it's a good one: the media does not focus enough on policy neglect as much as it focuses on policy failure. In doing so, corporate media allows the government to define the scope of the national conversation. More importantly, however, in an administration such as this, its failures do not, most likely, outnumber its negligence. This analysis, as helpful as it was, neverthless obscures the more important questions: (1) Is Katrina an issue of racial poverty? and (2) Has the media changed its portrayal of black Americans and politics? What benefits do Americans accrue by viewing Katrina as an issue of race? The negative consequences, in my mind, outweigh the positive. The benefits of the racial poverty angle, for people like Shipler, are that it: (a) demonstrates the public neglect of the intersection of race and poverty, (b) decreases the likelihood that blacks will vote for Republican presidential and congressional candidates, (c) offers reasons why the federal and state governments are still necessary, and (d) proposes further modifications to the United States defense and infrastructure planning. The negatives, for people like me, are that it (a) underscores black Americans as being uniquely in need of governmental intervention, (b) threatens to break the progressive coalition by galvanizing people around either the issue of class or race, (c) under-emphasizes the role that properly functioning governmental agencies can have, and (d) will be seen as an excuse to defund other governmental initiatives. In a way, I sympathize with Shipler's desired project of re-centering issue areas where the federal government can make a difference through involvement. However, as he himself noted, tackling racial poverty cannot occur within left-right discourses about limited versus expansive conceptions of the federal government. This national discussion needs to transcend those categoies to get to the heart of the matter. But can the nation sublate a left-right discourse without furthering harmful racialized discourses and ideologies? More important issue than trascending left-right binaries is this: in acknowledging that there are those persons in our country who have a truly terrible material existence when compared the relative affluence of the United States, to what extent will these persons be otherized as passive, foreign, racial, or incapable? Shipler calls for more public scrutiny and ackwoledgement of poverty and racial inequality; scrutiny and acknowledgement require an act of perceiving of one subject onto another. It is the dynamics of the public writ large perceiving the poor that worry me: how will those who need help be portrayed? If we are to have more public scrutiny on poverty will that scrutiny come with the usual historical baggage of the removal of agency or the impugning of blame onto the receiver of charity? Let me put it more concretely. Policy discussions on the issue of poverty, racial poverty, and governmental assistance tend to revolve around blacks Americans. The very fact that the idea of a "culture of poverty" still tends to surface in discussions about the black poor, or, that poverty becomes an issue of laziness and non-assimilation in the case of urban black and Hispanic (male) youth should reveal much about American thinking on the subject. It is the difference of those black and Hispanic male youth from us that is the reason for their poverty. These differences appear either as helplessness or pathologized, vagrant behavior. On the one hand, some policy analysts and politicians argue that absent intervention and involvement the poor--whether they are black, Hispanic, or female--would be helpless. Ironically, in a move made to "save" the poor from their circumstances, the poor are stripped of their agency and become politically relevant to the extent to which their behavior and lives are shaped by the governmental intervention. Many conservatives, particularly black conservatives, react very negatively to this. On the other hand, other policy analysts and politicians argue that poverty is merely a function of effort, qualifications, and worthiness. On the lazy or the weak are truly poor; opportunities abound for any who are intelligent enough to seize one. However, we know that a not insignificant portion of the material conditions of a person's life are determined by historical and sociological factors beyond their control. The family and social position into which one was born is primarily a function of randomness: you could have been born into some other family with a different social position. Liberals react negatively to the creation of super-agency and the absolution of responsibility and duties of some empowered social classes. There should be public awareness of the issues of iniquity, scorn, and stigma that arise from a person's social position in all of its complex axes of race, class, gender, religion, sexuality, country of origin, familial resources, etc. The justification of the duties that some who are in certain social positions owe to others requires a political conversation in which all persons distribute social and personal resources to increase everyone's ability for political and social action and inclusion rather than on images of pathologized, reified, big-"O" Others. Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Bush and Business-friendly Jurisprudence In my first post on the issue, I offered that the main reason Bush nominated Miers was due to her pro-business tendencies rather than her moral positions. It seems that Alito too is business-friendly. Indeed, the business of America is business. Presidents Say the Darndest Things Thanks to Demosthenesfor this tip. President Bush prodded China on Wednesday to grant more political freedom to its 1.3 billion people and held up archrival Taiwan as a society that successfully moved from repression to democracy as it opened its economy. Tuesday, November 15, 2005

How Conservative is Alito? The Agenda Gap has an excellent post by guest-blogger David Herman on Alito's very conservative beliefs. All the recent controversy stems from Alito's 1985 job application to be assistant attorney general under Reagan. Stephen Bainbridge, law professor, cheers Alito on in a post entitled "Alito on Abortion: Vindication for the Anti-Miers Crowd. In particular this quote of Alito jumps out at me: [Alito wrote that he believes in:] "very strongly in limited government, federalism, free enterprise, the supremacy of the elected branches of government, the need for a strong defense and effective law enforcement and the legitimacy of a government role in protecting traditional values." [Alito also noted:] In college, I developed a deep interest in constitutional law, motivated in large part by disagreement with Warren Court decisions, particularly in the areas of criminal procedure, the Establishment Clause, and reapportionment. There are several claims that I wish to bring forward to the reader's attention. Alito envisions a government that is (1) limited, (2) federal, and is (3) under the general guidance of the "elected branches." To move from the euphemistic to the concrete, I shall unpack each term very briefly. (1) A limited government is a government that restricts its size and influence to such a degree that the basic enforcement of free and equal rights for all is forsaken. Under a perfectly limited government, the political and legal institutions codify and legitimate the current holdings and social positions of the actors in that society; this has the net effect of transforming questions about the care of the least well off and the most vulnerable into question for power politics between the strongest economic and political actors of that society outside the institutions of representative, liberal government. Some situations require the government's presence to ensure the right to have rights. Gay marriage and a definition of freedom for the emancipiated slaves, I have argued, are good examples of this. (2) The word "federal" means a strong theory of state's rights qua themselves. I have argued in the past that the Constitution was never designed to protect the rights of states as an end in itself, but only as means to ensuring republican liberty for individuals. Madison provides what he considers to be an easy rhetorical question for his readers: "...was the precious blood of thousands spilt, not that the people of America should enjoy peace, liberty, and safety, but that the government of the individual States, that particular municipal establishments, might enjoy a certain extent of power, and be arrayed with certain dignities and attributes of sovereignty?" I added to the emphasis to highlight that Madison juxtaposes state's rights as ends in themselves to state's rights for the purpose of guaranteeing rights. As I wrote earlier state's rights suffered a huge blow during Reconstruction and then again during the New Deal when it became plainly evident that the states were not protecting individual liberties. Madison's radicalism did not diminish once the Declaration was written; indeed he offered that the motivating principles behind the constitution were more important than the historical forms by which these principles manifested: "It is too early for politicians to presume on our forgetting that the public good, the real welfare of the great body of the people, is the supreme object to be pursued; and that no form of government whatever has any other value than as it may be fitted for the attainment of this object." The teleology of government is the protection of the people; its power the people's consent. I shall address (3) in refuting Brainbrige's defense of Alito's exclusionist jurisprudence. In particular, Some bloggers, in commenting on Alito's response, have gone so far as to conclude that he is "against democracy." Bainbridge responds that to infer such a thing is an awfully "thin read" of Alito's response, which, he argues must be taken in context. As Bainbridge reads it, Alito is not objecting to reapportionment qua reapportionment, but rather to the overall mindset of which the reapportionment cases were a part. I would disagree with the claim that Alito is against democracy per se. He clearly believes in states, the Congress, and the Executive. My claim is that Alito's restrictive view of the judiciary confines and extirpates one of the corrective institutions of our federal government. When political maneuvering and bigotry leave some citizens--like gays in relationships who wish to start families or emancipated blacks after the Civil War--vulnerable to the ideological machinations of uncaring titans, the judiciary, as the protector of the Constitutional principles animating our liberal democratic regime, may be the last recourse for those who need federal action. Without the judiciary, those human beings being tortured at Guantanamo and those persons whose relationships have become stigmatized due to the bigotry of a few and the indifference of many would be condemned to have their dignity and humanity denied. The United States posses a federal government composed of three co-equal branches. I have written in the past that "institutional and precedent conservatives are also unwilling by disposition to create new precedents to better defend and protect non-privileged persons. The Supreme Court of the United States, and its lower courts that operate under it, share a co-equal burden in the governance of America. Precedent conservatives...should respond to the challenge and govern co-equal." The judiciary is an important check on the Executive and legislative branches; if any branch does not uphold its task of ensuring liberty for all, the other branches of government have powerful mechanism to prevent its partners from doing bad things and potent capabilities to set the government back onto the right track. Bainbridge would criticize my ideal court as activist. In response I would offer that only when the other two branches have (1) failed to act or (2) are acting in a manner incommensurate with their duties to protect the most vulnerable and the least well-off should the judicial branch "take the lead." At all other times, it should operate co-equally with the other branches, being neither overbearing nor deferential. In a few cases, like Reconstruction, the Executive and the legislative led the way to freedom. In many cases the judiciary is that light. No branch of our federated governmental structure is going to be the best moral actor all the time; however, if any one the branches relieves itself from the duty of protecting its citizens, the likelihood of justice being deferred radically increases. Alito, then, is too conservative if he is unwilling the bear the responsibility for being the head of one of the branches of the United States government is role no less or more important than any senator, representative, or member of the Executive staff. Monday, November 14, 2005

Bush: War Criminal? Eric Posner has an insightful post on that question at the UChicago Law Faculty Blog, particularly, because he goes through the evidence and ulitmately concludes its a meaningless thought exercise. Money quote: So is Bush a war criminal? Perhaps. But we are all legal realists now, so we need to ask whether it matters if Bush is a war criminal. Probably not, because no court is likely to try him. Other states have no interest in pressing the question because they would not want to acknowledge that their own leaders could be tried and convicted on similar theories, nor would they want to risk losing American aid or cooperation. Why is international law called "law"? Equality under the law only means something if there is a sovereign to back it up qua itself. International "law" on the other hand seems to me to be merely a codification of the exercise of power by some to the detriment of others. That isn't law in any true sense of the word. As for my opinion, since we are all legal realists now, it doesn't matter that Bush can't be a war criminal. Indeed, Posner is right that "it would require the conclusion that many recent American presidents – including Truman, Kennedy, Reagan, and Clinton – were war criminals (or arguably so, in some cases indictable but not necessarily convictable), as well as most of the leaders of western nations that have recently employed military force or violent covert operations – and this includes France, Britain, Germany, and Israel, to say nothing of Russia and China." I'm not particularly invested in trying, indicting, or convicting Bush per se. But we shouldn't have to chose between idictment and silence. However, I think Eric's proposition that: "the claim that modern statecraft is criminal is not useful. If the category is to be applied to leaders, one needs a definition of war crime that permits an overall assessment of the good as well as the bad that the leaders accomplished. But this is politics or political morality, not law" excuses too much. He's right that calling modern statecraft criminal doesn't really matter for politicians and statespersons. It does matter, however, if the special tribunals and international courts continue to overlook America's role in fermenting these disasters and breaches of international morality. International law further decreases in its "law" status if it simply comes to mean "the set of norms and principles codified in legalese that are applied to our vanquished enemies." Bad things happened in the past, in part, because of American interference; acknowledging that should case no great harm. International law loses more, I think, if these tribunals ignore, overlook, and disavow American responsibility--even if we can't find legal culpability due to realist concerns--while making the bad guys that we've dethroned out to be monsters. For all those devoted readers of this blog, and I heart you, this is not the post of the day. There will be one much later today after classes and homework. Hopefully, I will finish a response to the article on feminism that Rabbi Gray sent me. Enjoy your day until then, and stay tuned. Sunday, November 13, 2005

The Reading List Alright, this is the reading list from now until January 2. Let's see how many of these I can finish before I have to start thinking about, in a concrete and systematic way, what I am going to write my MA thesis on. Non-fiction Enrique Dussel, Beyond Philosophy: Ethics, History, Marxism, and Liberation Theology Jose Marti, Jose Mart Reader Gina Barreca, Babes in BoylandStephen Brooks, Producing Security Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks Howard Ball and Phillip Cooper, Of Power and Right Noelle McAfee, Habermas, Kristeva, and Citizenship bell hooks, All About Love Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists Emmanuel Eze, Achieving our Humanity Ellen Meiksins Wood, Empire of Capital Page Smith, The Rise of Industrial America Fiction Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude George R. R. Martin, Feast of Crows These books are in no particular order, and, there is an asymmetry between fiction and non-fiction. This partly has to do with my reading interests--I prefer non-fiction--and partly has to do with a lack of recommendations concerning good fiction that I might read. Though since only three of the books on this list have a direct relation to international relations literature, the other texts are bonus knowledge representing a pool of information that may not be directly shared by others who share my interests. My excuse for the fiction is: (1) Solitude is a classic and was purchased for me last year so I should read it, and (2) Feast is the most recent book in a series that some friends and I are reading together. Friday, November 11, 2005

Humanity in an Age of Terror: Reflections on the Riots in France I got an excellent tip from Connor on The Little Green Blog. He wrote: "If you are the sort of person who actually wants to know why riots are happening in France, you are probably the sort of person who should read this Afro-French chick's blog. It's been passed around a lot but it's quality." True to form the website is very instructive. In my most recent post about the French riots, I forwarded the theory that the French riots were a reaction to the hard-line taken by the French interior minister and the police brutality that followed, which also led to the deaths of the two black youths. I argued that the proposition that the rioters were burning cars because they were black or poor was insufficient persuasive as a causal explanation of the violence; rather the racially and economically stratified nature of French society and its politicization of the black woman's body and her progeny as a threat to the French nature accounts for the character of the violence. This blog seems to confirm my theory in two ways. First, the title of the post is "Mort pour rien - Dead for nothing." The choice of title immediately indicates the tragedy of the situation: the lives of two youths were thrown away simply because they were black. The author maintains this posture in the opening paragraphs and is worth quoting at length. The riots were triggered by the death of two youths of African decent, Bouna Traore, aged 15, and Zyed Benna, 17, were electrocuted at an electricity sub-station in Clichy-sous-Bois as they ran from the police. A third youth who escaped death, said they panicked and ran because they found themselves near the scene of a break-in incident where police began to arrive. The police of course deny any involvement in the boys death. It should be noted that these young people are not immigrants. Their grandparents and possibly their parents are but they are born in France and are French citizens. Constantly referring to them as "immigrants" is a problem in itself and reinforces their exclusion from mainstream French society. Second, the police overreacted to the intiatial response to the dead youth. The author then observes, "Following the death of the boys on Thursday there were two days of riots. On the Saturday community members in an attempt to calm the situation organised a silent march in memory of the teenagers." The author's re-telling appears to complicate my story somewhat because the original riots were only two days. In fact, another damning piece of evidence against my theory is that these riots typically break out and at least 80 cars a night reguarly are burned around Paris. (I noted that frequency of the burnings in my original post.) This evidence, however, is not as damning as it seems for I argued that the hardline of the minister and the police brutality led to the big riots. The minister's declaration of war on the "scum" charged the atmosphere; the police's brutal response to the peaceful protest (which I will detail below) leads to the rioting. In the evening, some 150 young Africans met with the Mayor to discuss the events. The mayor talked about the cost of the damage but did not make any reference to the heavy handed policing. The youths became very angry at the police, the repression, the abusive language directed at their mothers, calling them sluts. The police began to arrive with flashballs (for shooting rubber bullets) and riot gear provoking the crowds. They then told the brother of one of the dead youths to go home. He took three steps towards the police who then began to fire tear gas at the crowd. The following day, about 8.30pm on Sunday evening there was another incident which took place around the local Mosque. By this time according to Netlex things had calmed down but it seems the police presence was heavy in the area. It is not clear what exactly happened but the police released tear gas grenades one of which landed in the local Mosque during prayers which was full of families. A panic followed as the building filled with smoke and people were crying and coughing and running. It is this incident that triggered the riots again and they have continued ever since spreading into a worsening situation and spreading to other French cities. Laurent Levy, whom the author quotes, and whose reflections I shall also reproduce, also credits the charged atmosphere created the by Interior Minister and the police for the situation. Why did the Minister of the Interrior make a point of saying that these events took place following an attempted theft? Doubtless, he wanted to play on the fantastic and disastrous idea that people have of the “suburbs,” an idea that he himself helps to spread. That they are lawless places ruled by criminals, threats to public safety, breeding grounds of delinquency. Levy's and the African-fem's outrage is one of the many expressions of people looking for their humanity in the 21st century. Message to democratic governments of the world: do not sell the lives of your poor short. We, the poor, have our humanity and our dignity. We will not be denied. All to often in America the politics of race, crime, and class are conflated to justify inhumanity to some of the nation's most vulnerable citizens. This must stop. Thursday, November 10, 2005