The Dartmouth Observer |

|

|

Commentary on politics, history, culture, and literature by two Dartmouth graduates and their buddies

WHO WE ARE Chien Wen Kung graduated from Dartmouth College in 2004 and majored in History and English. He is currently a civil servant in Singapore. Someday, he hopes to pursue a PhD in History. John Stevenson graduated from Dartmouth College in 2005 with a BA in Government and War and Peace Studies. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. He hopes to pursue a career in teaching and research. Kwame A. Holmes did not graduate from Dartmouth. However, after graduating from Florida A+M University in 2003, he began a doctorate in history at the University of Illinois--Urbana Champaign. Having moved to Chicago to write a dissertation on Black-Gay-Urban life in Washington D.C., he attached himself to the leg of John Stevenson and is thrilled to sporadically blog on the Dartmouth Observer. Feel free to email him comments, criticisms, spelling/grammar suggestions. BLOGS/WEBSITES WE READ The American Scene Arts & Letters Daily Agenda Gap Stephen Bainbridge Jack Balkin Becker and Posner Belgravia Dispatch Black Prof The Corner Demosthenes Daniel Drezner Five Rupees Free Dartmouth Galley Slaves Instapundit Mickey Kaus The Little Green Blog Left2Right Joe Malchow Josh Marshall OxBlog Bradford Plumer Political Theory Daily Info Andrew Samwick Right Reason Andrew Seal Andrew Sullivan Supreme Court Blog Tapped Tech Central Station UChicago Law Faculty Blog Volokh Conspiracy Washington Monthly Winds of Change Matthew Yglesias ARCHIVES BOOKS WE'RE READING CW's Books John's Books STUFF Site Feed |

Sunday, December 23, 2007

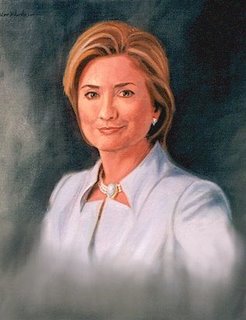

Why Hilary Clinton is Not Out of the Race Yet Since October 30th's debate, Democratic front-runner Sen. Hilary Clinton (D-NY) has been (depicted as) sliding to parity with Sen. Barack Obama (D-IL) in the crucial early states of Iowa and New Hampshire. After a very poorly performing summer, Obama seems back in his element, and, in combination with clever attacks by former Sen. and Vice-President nominee John Edwards (D-NC), the once inevitable Clinton machine, who had, in September seemed to have all but wrapped up the race, is vulnerable and poised for a defeat. Supporters of Sen. Clinton for president, however, need not be worried for three reasons. One, the best part of the Clinton machine, and one of the reasons that she would make such a wonderful and effective executive, is its attention to detail and voter turnout. For those with longer political memories, you will recall the flap, earlier in 2007 (around May), then Sen. Clinton's campaign staff was thinking about skipping Iowa entirely and focusing its efforts on New Hampshire and South Carolina. Her main advisers knew that campaigning in the state was going to be a time and money suck, with little likelihood of a first place finish (particularly given Edwards has been living in the state since the end of the Kerry coalition). In fact, in May 2007, Sen. Clinton estimated support was 21% compared with 23% and 29% for Senators Obama and Edwards, respectively. What did Sen. Clinton do in the face of such odds? Answer: enlist the support of former governor Tom Vilsack and Democratic legendary organizer Teresa Vilmain. According to the Wall Street Journal, "Ms. Vilmain first organized in Iowa in 1988, at age 29, working for eventual Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis. This time, Democrats' turnout in the state that kicks off the presidential race is expected to set a record, given excitement about the seven-candidate presidential field and the prospect of taking back the White House. More than at any time since the caucuses gained prominence 32 years ago, organizers such as Ms. Vilmain are searching for ways to draw voters who have never participated in a caucus." Vilmain and Vilsack, who together engineered a two-term victory for the Democratic governor, have built a formidable political network of enthused Clinton caucus goers. They're hard work has paid off: in October, at the height of Clinton enthusiasm, Sen. Clinton had 29%, compared to 22% and 23% for Senators Obama and Edwards, respectively. (The month of November in the wake of the October 30th debate, however, was tough and now Clinton has sunk to 25%, with 28% and 23% for Obama and Edwards, respectively.) What's crucial to note is that at the time her campaign staff--the Clinton machine--made choices about investment strategies, Edwards and not Obama, and the prospects of an Edwards-Obama two-way race, were the greatest dangers for Clinton. Clinton's actions, and the experience of her team, made what should have been a cakewalk for Edwards and an easily media opportunity for Obama, into a competitive three-way race that for a long time she dominated. The Clinton strategy has always relied on New Hampshire as its firewall, a lead that has been eroding since Obama found some holiday momentum. Rather than conceding, or sticking to the same strategy that she had been using, Clinton dispatched another Democratic legendary organizer, Michael Whouley, to New Hampshire. Mr. Whouley is a wizard of turnout victories. Marc Ambinder summarizes the modern magician this way: "In 1992, Whouley served as national field director for the Clinton-Gore ticket. In 2000, Whouley is credited with forcing Gore to engage in more retail policking, a decision that helped to save his campaign in New Hampshire against Bill Bradley. In 2004, he helped John Kerry turn around his fortunes in Iowa. He was Kerry's anointed field czar in the general election, and, horrors, actually found himself conducting telephonic phone briefings with the press." Moreover, Whouley's proteges David Barnhardt and Karen Hicks have been in New Hampshire for months and designed the Clinton campaign's sophisticated turnout program, he as caucus director and she as the planner. Second, Bill Clinton is big asset to her candidacy and campaign. His constant gaffes and screw ups are a bit annoying, but he still does have star power, and is one of the best centrist Democrat strategists whose actually run for the party's nomination. Unfortunately, former President Bill Clinton sucessfully came out of no where to win the nomination, and thus, by existing, give some of his legacy to Sen. Obama as well. Third, the Democratic Coalition will probably pull through for Hilary in ways that it cannot for Obama or Edwards. Sadly, there is some decent statistical indicators that voting Latinos tend not to vote for black candidates and have negative perceptions of American blacks in general. I'm afraid that not only with the Latino vote tend toward Hilary in the Southwest, but might also defect to Republicans in the general election. (Now of course we have that whole immigration discourse to deal with, but we'll see.) Oddly, though, it's hard to know how much Latino support for Clinton will be off set by white support for Obama, precisely because he is black. Moreover, significant portions of the black vote loves the Clintons and trust them, and centrist Democrats in general, to fight for middle and working class black issues. Senator Clinton has played her cards right in highlighting the gendered dimension of race, particularly with respect to AIDS and HIV, giving voice to discourses that many black politicians overlook when talking about the "community." The gender issue also plays well with working class women who tend to see the glass ceiling as something real and right above them. This sense of Senator Clinton putting in her time and working hard plays to their sympathies as well as attracts union support. Lastly, gay and lesbians, particularly after the Donnie McClurklin flap, wonder what an Edwards or Obama Democratic party would look like for them. Even after the dreadful "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" compromise that resulted from Bill Clinton polarizing the issue of gays in the military before he was willing to spend political capital, gay leaders seem to trust the Clinton's more (no surprises) that the more conservative Edwards and the more symbolically tied to black social conservatism Obama. Wednesday, December 19, 2007

Predictions for Iowa and New Hampshire As everyone disappears for the Christmas and New Year's holidays, I wanted to get my predictions for the first two contests, Iowa and New Hampshire, out there. Iowa Iowa, as we know, has attracted a lot of attention this election cycle because a crowded field on both sides, as well as several major names being in play, makes the state's caucuses a must-win for some of the lesser known candidates, and a headache for candidates with higher numbers. One of the most important things to note for Iowa is the vote-switching that takes place as the some caucus-goers settle on their second choices whereas other try to create momentum for their primary (no-pun intended) choices. The pressures begin as soon as the caucus-attendees arrive in the parking lot to witness which delegates seem enthusiastic about their candidates and which delegates will probably have to defect to other groups once their candidate's "support" is revealed. Due to the voting effects of these literal lateral social and networking pressures, as well as the immense importance attributed to the first and second place winners, two strategies will collide head to head that night, neither of which is mutually: the politics of charisma and the politics of mobilization. The politics of charisma shores up the enthusiasm of the delegates for a particular candidate and provides ample social capital to tip support toward a particular candidate. The politics of mobilization turns out a sympathetic demographic and prays that initial support is strong enough to prevent massive defection to another candidate. On the Democratic side, Edwards and Obama have mastered charisma, and poured a lot of resources into mobilization. Clinton, while less charismatic, has designed a buddy-system turnout method, which should withstand early pressures for defection, and enlisted several popular locals: Magic Johnson, Bill Clinton, and former Governor Tom Vilsack. On the Republic side, former Governor Huckabee has a lock on the politics of charisma--though monetary constraints have prevented him from investing into organized mobilization strategies--and former Governor Mitt Romney, through investment, has created a mobilization effect. Rudy Giuliani has only half-committed to the state. Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) has focused mostly on New Hampshire, but has received crucial endorsement nods as well as a lot of press from the surge. As such, I predict (in this order) for Democrats: Edwards, Clinton, Obama, and for Republicans, Huckabee, Romney, and McCain. I think that caucus trading between the enthusiasm of Edwards supporters and Obama supporters will weaken them both, and that, more importantly, Clinton, through the buddy system has inoculated many of her supporters from defection through the buddy-system (a source of mobilization as well as monitoring). Moreover, Edwards supporters are pissed that their candidate has been ignored in the press and will be prepared to court and collect any soft support. The nod from the Des Moines Register will improve Clinton's image for long enough after Christmas to have her fold in at least Gov. Bill Richardson's support and potentially Sen. Joe Biden's as well. (Generally, people support those candidates for experience and wonkishness rather than charisma.) I think that Dodd's and Kuchinich's appeal is more left-leaning and will disperse, roughly evenly, to Obama and Edwards. As for the Republicans, I think that Romney machine has created a floor beyond which he cannot fall, and that enthusiasm for Huckabee is at an all-time high. Moreover, Huckabee can count on religious networks to mobilize communities for him, and to prevent defection by having them pre-organized along social ties of monitoring and enforcement. Giuliani's lackluster campaigning will force his supporters into the arms of a candidate is tough on security, John McCain, who also recently received the nod of the Des Moines Register as well. McCain will probably absorb a lot of other support, particularly from Thompson, as a candidate who can stop both Huckabee and Romney from becoming the nominee of the Republican party. New Hampshire In New Hampshire, the battle is for independents. However, without Iowa sending them a strong signal about which race is more dynamic, the Independents will probably divide their support among Republican and Democratic candidates, hurting those candidates who have most courted the Independent vote, Senators Obama and McCain, to overcome any weakness they have within their own parties. Moreover, the Clinton machine is furiously organizing the people of the New Hampshire, even the Obama's performance has his numerical support rising. Without the independents voting mostly for Obama, or seeing a renewed interest in McCain in the wake of a good Iowa finish, I predict the following results for New Hampshire. For the Democrats, Clinton (narrow), Obama, and Edwards. (This is really going to put South Carolina in play.) For the Republicans, John McCain, Ron Paul, and a Mitt Romney/Huckabee tie. McCain is very popular among New Hampshire Republicans now, a good showing in Iowa, as well as the recent endorsements of the New Hampshire papers and his team's focus on New Hampshire will probably swing the state for him. (Moreover, a resurgent McCain will reabsorb the Thompson off-shoot that emerged when the McCain team ran out of money and the Giuliani security hawks.) Ron Paul's money and the libertarian diaspora within New Hampshire's Republicans will create a solid finish for Ron Paul, giving him some much needed media space. Ron Paul's grassroots campaign is the most sophisticated of all the Republicans, and will greatly appeal to the small-government types who live in New Hampshire. Mitt Romney, again, due to money and time, will probably have a floor that will not evaporate, but Huckabee is going to have a run of the press for at least seven days after his Iowa victory, and growing numbers in South Carolina that will improve his image of electability. Clinton will scoop out a narrow turn-out victory and descend on South Carolina as the friend of blacks and a the Democratic-comeback kid. (She will emphasize that she was the front-runner, whether the attacks, and campaign equally hard to win the affects of South Carolina. Most of her generals, however, will go to the Southwest and California as she wins the non-primary primaries in Florida.) Obama-mania will not have subsided in the wake of a non-Iowa victory, and, more importantly, Edwards will have to step up attacks on him, giving him more press time. Edwards, unfortunately, will not be able out maneuver either the Obama or Clinton grassroots campaigns, and, sadly, is not the fascination of the press (who like the idea of a Clinton-Obama fight). Edwards, too, will have to run to South Carolina and effectively cede the Southwest to Clinton. The following people will have to leave after New Hampshire and Iowa: Joe Biden, Chris Dodd, Fred Thompson, and Rudy Giuliani. Fred will probably endorse McCain as will Rudy to stop Romney and Hucakbee. Bill Richardson won't leave until Clinton has dusted off his campaign in the Southwest. I'm not sure when Dennis Kucinich will drop out. Tuesday, October 30, 2007

The Israel Lobby I rarely venture into books on contemporary politics, but I enjoyed Mearsheimer's Tragedy of Great Power Politics (even if I disagreed with a lot of it) , had some time on my hands, and decided that the furore surrounding the original article and book was too great to ignore. Well, I have just finished the book, and am pleased to report that I learned much from it, including the extent of America's economic and military support for Israel, stuff about Israel's founding and wars against its neighbours that I didn't know about (but which historians like Benny Morris have re-examined), and the peculiar phenomenon that is Christian Zionism (whose origins I had begun to read about in Michael Oren's Power, Faith, and Fantasy -- alas, I've never gotten around to completing it). The core of the book, of course, is that the eponymous lobby's influence on US attitudes towards Israel is 1) bad for America, 2) bad for Israel, and 3) bad for the Palestinians. The authors are clear, concise, and thoroughly reasonable: they anticipate and tackle objections (including accusations of anti-Semitism), clarify important points, and avoid ideological and rhetorical extremes without compromising the overall force of their argument. I especially like how they implicate the lobby by using its own words against it (cue accusations of Dowdifying the evidence or relying excessively on secondary sources, which, given the nature of the topic, are pretty much all that's available). Attempts to silence the authors' arguments about the lobby and free speech ought simply to strengthen these arguments. The one criticism I have is obviously from the perspective of a non-specialist: I'd like a longer and more prescriptive conclusion. Historians aren't supposed to be prescriptive, but political scientists can and should be. Unfortunately, Mearsheimer and Walt, while agreeing that the lobby's influence needs to be mitigated, are rather vague on how this might come about. For instance, they write that: To foster a more open discussion, Americans of all backgrounds must reject the silencing tactics that some groups and individuals in the lobby continue to employ. Stifling debate and smearing opponents is [sic] inconsistent with the principles of vigorous and open dialogue on which democracy depends, and continued reliance on this undemocratic tactic runs the risk of generating a hostile backlash at some point in the future.America needs a more open debate on its support for Israel, and a more even-handed relationship with the country, but given the strength of the lobby, what concrete steps are needed to make this happen? The authors urge the government to use its "considerable leverage" to sway Israeli policy-makers, apparently forgetting the lobby has its own "considerable leverage." Legitimate criticisms of their book, like this one by Martin Kramer (whom the authors identify as part of the lobby but not a neoconservative) should focus on the extent to which Israel is a strategic asset or liability and offer more than the usual talking points on Israel's moral and democratic credentials. Bad criticism leans towards accusing the authors of anti-Semitism, which the right uses to bash the left in pretty much the same way that the left uses "racism" to bash the right. Consider this laughably simplistic piece by George Shultz. It's not quite as vicious as something by Alan Dershowitz or Marty Peretz, but it's still utterly unencumbered by knowledge of the book. It's always a good idea to read a book before "reviewing" it; every single accusation or veiled accusation the former Secretary of State makes is demolished in the book. Let me cite just a few examples:

Sunday, September 23, 2007

Selling (Out) The Revolution: Re-thinking Social Movement Theory I've always been a little bothered by the distinctions between "real social struggles", struggles that in theory many people can get behind, and particular struggles, or struggles that only appeal to a certain people. This conundrum is a particular problem that liberals face when trying to build their leftist coalition and have to choose between the politics of reform and the politics of 'difference.' A lot of people are surpised that the Democrats haven't tried harder to end the war in Congress and sooner. The netroots are a little peeved that the moderate Democrats, until now, have focused more on wooing the moderate Republicans, who still toe the party line, than ending the war in a showdown of government. Some pundits worry that the failure of the Democratic Congress will demoralize voters in 2008. In a way, people should not be suprised. Without 58+ votes in the Senate, it's hard to get anything done (as cloture requires 60). More importantly, however, in absense of wide-spread devastation, the true change will always be thwarted at the elite level by the grab for political power. Craig Calhoun, a theorists of social movements, writes: “’Identity politics’ and similar concerns were never quite so much absent from the field of social movement activity--even in the heydays of liberal party politics or organized trade union struggle--as they were obscured from conventional academic observation.” Moreover, these labor and social democratic struggles not only dominate the field of social movements, but force all other organizing “aimed at economic or institutionally political goals” into the residual alter-concept of “new social movements.” For scholars of social movements, labor and social democratic struggles are thereby differentiated from the new social movements both economically and politically. Economically, the analytic of social-labor movements dramatize and illustrate the singular set of social questions of industrial and post-industrial capitalism: the amount of redistribution and the character of national political economy. (Gilpin 2001) Politically, these labor and social democratic movements sponsored new political constellations of governance, making possible public policies avoided by the non-labor elites and creating the foundations for a general, “utopian” transformation of the society by the state. In contrast, new social movements are particular in their constitution, parochial in the worldviews, and without a broad coalition with which to capture to political power: characterized derisively by the moniker “identity politics.” Why did scholars lionize the labor movement, and, in the process, downplay the preceding and succeeding “new” social movements? What makes some movements real and others ephemeral, merely cultural, or just plain ignored? Scholars celebrated the labor struggles for two reasons. First, the politics of labor and the public policies social democratic movements stood for and enabled seemed more normatively universalizable and politically feasible than their identity politics counterparts. For Marx and many theorists who followed him, the lived experiences of workers and class structures exhausted all of the politically relevant subaltern identities. After realizing their oppression, the laboring classes could capture political power and transform the social bases of their oppression into an emancipatory dictatorship of the proletariat. Post-Marxian theorizing appropriated this Marxist logic of representative social classes without buying the orthodox eschatological yearnings for the Revolution. Habermas, as one example, argues that the bourgeois class can constitute a democratic public comprised of political individuals. What is important in history is that bourgeois as a social class can found a publicly rational, inclusive, and democratic political space Second, identity politics seemed parochial, less inclusive, and less ‘traditionally’ political. Identity politics, in that it does not necessarily lead to distributive struggles, is based on ascriptive and expressive identities. As such, according to Calhoun, new social movements seek to “politicize the personal.” Why does this debate over the history of social movements matter for the study of revolutions? The debate is important because it illuminates how revolutionary social movements transform into political movements by abandoning any real struggle for social change and accommodating themselves to the powers that are. Social movements lose hold of the revolution by grasping for political power. In this debate, revisionist theories of new social movements do not simply complicate the happy history of social movements, or even merely de-center white laborers as the source of social change. They demonstrate the trade-off between revolution and politics within social movements, which emerges from the fact that all polities are founded upon hierarchies of difference. After E. P. Thompson’s magisterial work, no one can seriously doubt that a social movement’s political power, in this case the English working class, is tied to its active participation in and support for hierarchical orders within society. (See also Calhoun, 183-184) These hierarchical orders are the social power relations—of race, gender, sexuality, and indigeneity—which constitutes difference and enables denigration. At the top of these social hierarchies are the masters and the elites; at bottom, the subalterns. Social movements are revolutionary to the extent that they seek to challenge and contest these hierarchies; as Calhoun notes, “Roots [make] many movements radical, even when they did not offer comprehensive plans for societal restructuring.” These roots necessitate a focus of the movement on the power relations of society since social movements in general, for Calhoun at least, are premised on a defense of a ‘lifeworld’ from colonizing structures. The paradox of these social movements, and the key problem for theorists of revolution, is the trade-off between social transformation of hierarchal orders and aspirations to political hegemony. The aim of political change is to capture, or through coalitions govern, state institutions and the levers of power. As Ernest Laclau theorizes, “a certain particular, by making its own particularity the signifying body of a universal representation, comes to occupy—within the system of differences as a whole—a hegemonic role.” All social movements emerge from particular identities, whether that identity is that of the worker or of the woman. Some social movements and the social democratic movement in particular, attempted to, on the basis of its particularity, found a system of political economy and representation for the state as a whole. Whether Marx’s proletarians or Habermas’ bourgeois, to attain political power, social movements claim to represent the set of universal questions and identities posed by sulaterity’s existence. For Laclau, this move toward political representation “is exactly what we call a hegemonic relationship… A class or group is considered to be hegemonic when it… presents itself as realizing the broader aims… of the population.” To cater to the kind of coalition necessary to govern, social revolutionaries must abandon their social goals. Therefore, for the political movements, the defense of the ‘lifeworld’ from colonization is premised upon a quiet, but expeditious, assimilation into the colonizing structures themselves. Consider the case of the Enlightenment. “It is more accurate to the call the ‘enlightenment’”, Eric Hobsbawm notes, “a revolutionary ideology, [whose object] in spite of the political caution and moderation of many of its continent champions... [was] to set all human beings free.” In practice, however, Hobsbawm wryly noted, “the social order which [emerged]...would be a 'bourgeois' and a capitalist one,” a far cry from what we could imagine emancipation to be. Hegemony, a political goal, only comes at the expense of revolution, a social goal. Revolutionary social movements, in contrast, seek to recast the social hierarchies which enable some horizons and life choices while foreclosing others. These hierarchies possess political and economic dimension because the social orders that emerge from the hierarchal relations deny equal political subjectivity and constitute a socioeconomic division of labor to the subaltern elements. The hierarchies have largely been about moving the natives off the land, the women into the kitchen, the blacks back into the fields, and, in late modernity, the gays back into the closet. Many political movements acknowledge these social orders by playing up the political and economic consequences of the social order in an attempt to sell their platforms to constituencies, but in the process sell out the prospects of meaningful social change for political allies. This is not to push the distinctions between the political and social too heavily. In fact, most social questions surely have a political and economic dimension. The Negro question, for example, was about both citizenship and labor for most of American history. However, the essence of the social question and its revolutionary potential, lies in the challenge to the very relations of power and subjectivity making those questions possible. Therefore, the Negro question in American history can be expressed, in part, in terms of suffrage and redistribution, but only in part. The revolutionary aspect of the Negro question acknowledges that the question was not and never will be really about the Negro, but rather always about the racists trying to maintain a racial hierarchy while keeping blacks in their places. (Satre) The challenges to the racial order have nonetheless sold out as well. To attain a place in society, movements for black liberation have embraced anti-feminist and heterosexist politics. Loosing sight of this revolutionary core of social movements is what mainstream analysts did when they erased the old “new” social movements to perpetuate the mythopoetic narrative of the golden age of social democratic labor movements. This is unfortunate because the social revolutionary prospect is the only moral justification that participants in social movements have for engaging in acts of violence and disobedience to law. Therefore, it is disgustingly criminal and grossly immoral for elites to murder, rape, and pillage for political power; but justified—and some would even say welcome—for a slave to rise up against the masters who have raped for generations, to slit the master’s throat, and to burn his house down with the master’s corpse, his wives, sisters, and children still alive inside. Only black feminists have grasped this paradox. Thursday, September 20, 2007

I'd like to mention the blog of a friend, to which we will now link on this site: http://fiverupees.blogspot.com/ And he'd thought that we would never link to him. A Little on Why I am Supporting Hillary Clinton Since the Democrats won Congress, I've been making three predictions: (1) That Clinton would capture the Democratic nomination (due to superior organization), (2) that the most organized campaign on the Republican side (McCain) would flounder until Thompson joined the race (and become a two way race between those two candidates), and (3) that the presidential election would come down to whether Clinton could take the Southwest and a few Southern states. (Note a Clinton-Obama ticket would make the South very competitive due the black and Latino votes). In a few weeks I'll post my projections for Congressional Elections. It's going to be a Democratic House, but the real action is in the Senate. So far it seems that I am right. A lot of people have asked me: why I am supporting Clinton? Quite simply, she is a pragmatic candidate with foreign policy experience who is a policy wonk, who will also be able to get Congress to pass her legislation. I can count on her to get the right policies passed. (Which is more than I can say about any other candidate in the field.) I was just thinking a super-shrewd strategy is for Clinton to appoint Lieberman to be SecDef, getting him out of the Senate. Lieberman is a part of her DLC-wing of the Democrat party, he's tough on defense (like her), and she'll get a more reliable Connecticut Democrat (rather than a Democrat-leaning Independent) in the Senate to be appointed by the governor of Connecticut. Lieberman would have no trouble getting confirmed either. So I'm thinking a good cabinet for her would be: Lieberman- SecDef Obama- Vice President Edwards- Labor or HUD EPA- Al Gore Bill Clinton- unofficial ambassador to the World, deputy chief of policy planning This would be a strong signal to her base that she was committed to having the best possible Cabinet, and, all of those people would be easily confirmable by the Senate. Monday, February 05, 2007

Why Obama Must Navigate Racial Politics Carefully This post is inspired by reactions to a piece in the New York Times on why Obama "can't take the black vote for granted" in the primary Democratic elections. In response to this quote: "Obama isn't black" [...] "I've got nothing but love for the brother, but we don't have anything in common," said Ms. Dickerson, who wrote recently about Mr. Obama in Salon, the online magazine. "His father was African. His mother was a white woman. He grew up with white grandparents. many of the reactions have been more or less "I have no particular feelings either for or against Obama, but I have nothing but disgust for the modern conceits of identity politics." This post will takle the conviction that discussions of Obama's racial identity (by anyone, but especially black citizens) is a disgusting perversion of (an already problematic) identity politics. I strongly disagree that this particular form of identity politics is a problem, even though I vehemently disagree with the content and nature of the discussions about Obama's racial identity within some quarters of the black community. It is important for black voters to decide in which ways they will choose to support aspects of Obama's political message, because, whether anyone wishes it or not, an Obama administration would define discussions about race in America more hegemonically than other administration before. It is precisely because of the acute differences in the lived experiences of those persons who come to be portrayed as and identify with "black" American citizens that the Obama campaign will generate a lot of discussions within black communities about the nature of black political identity itself and what the tensions in that identity will mean for future discussions. These differences in lived experiences largely track along socioeconomic lines. It is an empirical fact that the kinds of people who end up being categorized as black who also attend elite institutions are (more often than not) of Caribbean or African immigrant ancestry and a middle-class background. The composition of those who end up being seen as black but who also "under-perform" usually lack (non-slave) immigrant ancestry and come from working and lower class backgrounds. (It is roughly the difference between the identity politics of Dartmouth's African-American Society, and those of the black student union at City College in New York.) Because the larger racial order lumps them together, there is an uneasy alliance between two classes who, other than the social meanings invested into their variegated skin pigmentations, have little in common socially, politically, and economically. Whereas immigrants and middle class black still largely support affirmative action--because its a useful tie-breaker for them-- working class black would prefer to live without the stigma and the misplacement that AA engenders. Working class blacks generally prefer a re-targeting of the American welfare state to provide less benefits to the propertied middle and upper-middle classes, and more to those persons who, for many reasons, historical and legal, do not live in suburban affluence. Failing a re-targerting, working class blacks support European-style universal welfare programs over the targeted ones of the current system. The black working class provides those members of society whose "averaged" African American LSAT scores at elite school is less than the "averaged" white LSAT scores. What *is not* important in these averaged scores, as opponents of race-based affirmative action would have you believe, is the discrepancy between the scores of blacks and non-black others. By definition, averages compress the extremes into a simplified statistic. That means that even in elite law schools there are blacks whose LSAT scores were significantly better than that of some of their admitted white classmates, even though through the language of (a rather convenient) appeal to "race blind" "justice" every white can claim to have been admitted on "merit" whereas blacks have to live with the stigma of preference. What *is* important is the spread/ distribution of scores. Black (and Hispanic) scores probably have larger variance than those of other groups. The qualified are pretty much guaranteed admission--in equal contests that candidate supported by affirmative action always wins--and admissions officers have to reach down to bring the target numbers up to a percentage range determined by them. Recruiting these lower scores to create a target population is what Justice Thomas lampoons as ethnic window-dressing. This variance is a reflection of the very different lived experiences of those Americans who come to be known as "black" and matters greatly for their respective worldviews, and, more importantly, for their social and political options within the hierarchies of capitalist society. That suppressed and rather testy discussion about black political identity, then, bubbles to the surface as many of the poorer and working class blacks, and their (largely self-appointed) ideological re-presentatives question loudly in whose interests Obama's racial constructions are forged. And they have good reason to believe it's not going to be in their interest. Lastly, many blacks fear that the election of Obama, or even his successful nomination. will be used as an excuse to close the chapter on an increasingly bitter celebration of the post-King civil rights era. (I say post-King because with King's mythologization as a democratic saint, popular histories about the period erase the tensions that were present even then, and project them into an equally mythological "betrayal" of King's "legacy.") Sunday, January 28, 2007

Hilary Clinton for President I'm temporarily emerging out from under the master's thesis rock. Let my support for her be known. This blog encourages you to donate to her campaign as early and as often as your budget will allow. If you exceed your limits, donate to the political action committees which comprise her network. More on Hilary as I am moved to do so.  |