The Dartmouth Observer |

|

|

Commentary on politics, history, culture, and literature by two Dartmouth graduates and their buddies

WHO WE ARE Chien Wen Kung graduated from Dartmouth College in 2004 and majored in History and English. He is currently a civil servant in Singapore. Someday, he hopes to pursue a PhD in History. John Stevenson graduated from Dartmouth College in 2005 with a BA in Government and War and Peace Studies. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. He hopes to pursue a career in teaching and research. Kwame A. Holmes did not graduate from Dartmouth. However, after graduating from Florida A+M University in 2003, he began a doctorate in history at the University of Illinois--Urbana Champaign. Having moved to Chicago to write a dissertation on Black-Gay-Urban life in Washington D.C., he attached himself to the leg of John Stevenson and is thrilled to sporadically blog on the Dartmouth Observer. Feel free to email him comments, criticisms, spelling/grammar suggestions. BLOGS/WEBSITES WE READ The American Scene Arts & Letters Daily Agenda Gap Stephen Bainbridge Jack Balkin Becker and Posner Belgravia Dispatch Black Prof The Corner Demosthenes Daniel Drezner Five Rupees Free Dartmouth Galley Slaves Instapundit Mickey Kaus The Little Green Blog Left2Right Joe Malchow Josh Marshall OxBlog Bradford Plumer Political Theory Daily Info Andrew Samwick Right Reason Andrew Seal Andrew Sullivan Supreme Court Blog Tapped Tech Central Station UChicago Law Faculty Blog Volokh Conspiracy Washington Monthly Winds of Change Matthew Yglesias ARCHIVES BOOKS WE'RE READING CW's Books John's Books STUFF Site Feed |

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

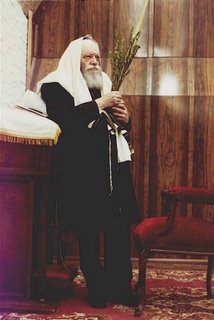

Why Chabad Matters for Non-Jews Hands down the best discovery of my junior and senior years was Chabad, complete with Rabbi Moshe Gray and his wife, Chani. I had every reason to be uncomfortable in a stereotypical Lubavitch household: being liberal, Protestant, black, and a recovering Zionist. Instead of a nightmare, I found one of most rewarding intellectual, spiritual, and social communities at Dartmouth. I. My Disaffected Dartmouth Days God, and the remembered and experienced stories of the power of the divine made manifest in human affairs, are very important for me. While I would have once described myself as theologically conservative because I believe that the Resurrection actually happened and that Christ was fully God and human, I now describe myself as a liberation theologist. That label simply means that theology, and the idea and concept of divine are more than conceptual artifices toward which and upon which we turn our mind's eye to contemplate in the stillness and the silence. Rather, to be saved by God is to be saved from this world for the purpose of furthering the divine imperative: "Love God with thy whole heart, mind, and body, and love thy neighbor as thyself." Salvation requires both a theological commitment to the sovereignty of God in our personal lives as well as the lived experience of caring for the widow, the orphan, and the oppressed. These theological beliefs have caused me to drift from the institution of a church who, as a social organization, contributes actively to the oppression and degradation of many of God's children. The most despicable face of my coreligionists appears in their politicized disavowal of the humanity of homosexuals (as if timeless divinely revealed truths would nicely correspond to the politicized differences of today), and, is also evidenced in the racist, classist, and sexist ideologies supported and encouraged by the same church. Jesus remarked "Be of good cheer because I have overcome the world." Heidegger, I think, provides the best meaning of what Christ might have meant by world. For Hedeigger, world was Daesein in which human beings interact by finding sites of meaning and significance in the being of others and in their crafted surroundings. Using this meaning of world, Christ calls us to rejoice for He has overcome the otherwise steel trap of repetitive human relations to create new possibilities for existence. The modern church, on the other hand, lacks both cheer and the overcoming of the world; instead, it grimly fights a hopeless struggle to codify the conditions of being-in-the-world to the advantage of those in the highest social positions at the expense of those who already suffer. The Dartmouth Christian community has not overcome its world--being at Dartmouth--and, as such, reproduce the pernicious, peculiar representations, hierarchies, and ideologies of that world. Whereas in the larger culture homosexuality is the politicized issue preventing the church from its overcoming of being-in-the-world, segregation tethers Dartmouth religionists. Segregation is rampant at Dartmouth on all lines save for gender. The rich segregate themselves, the whites segregate themselves, the gays segregate themselves (though to a much lesser extent), and the athletes segregate themselves. Unwelcome and disapproving glances greet those Dartmouth students who would dare to mix it up, and, frequently, the closest three friends of any given non-minority at Dartmouth are of the same race, class, and sexual orientation (as far as they know) of the person in question. The self-segregation of the whites and athletes, however, is even more pernicious than the active discrimination of the 1970s; the self-segregation cloaks overt and ostentation displays of white solidarity, save for when a hyper-concern to issues of race and affirmative action manifest in student discussions, and leads to this silly idea that every students stands alone for him- or herself in a world of heavily policed speech. These notions are comical because degrading suspicions turned onto minority and female sources of support (like Women in Science or Cutter-Shabbazz) and the frequent recourse that many minorities are admitted by affirmative action due to the lower SAT scores (an unfounded assumption)suggest that speech codes don't really exist. Moreover, we know that no Dartmouth student is "alone" in any meaningful sense of the word. Observing the long umbilical cords, the discrete transfer of monies, and the phone calls of support are not difficult. Even in situations where the Dartmouth student might be homeless or incredibly poor, financial aid and the supporting of loving friends more than compensates the lack of familial support. II. Chabadic Redemption Into this misery, Chabad was a breath of fresh air. Many liberal professors would find it hard to believe that a religious organization better embodied the best of American culture than many of their propagandistic sermonizing on the plights of minorities and American injustices. However, despite all the social engineering attempts to the contrary, the campus remained bitterly balkanized. Unlike campus, Chabad never felt segregated, and privileged no social position over any other. It seems odd that an organization designed to reclaim the Jews who were leaving their faith would feel so welcoming to someone who ostensibly had nothing in common with the organization. Besides being non-segregated and being welcoming in ways that the non-coed fraternities or Food Court could never be, Chabad was one of the few intellectually honest places on campus. All reasoned and considered views are welcome at Chabad; the Rabbi enjoys learning and listening to the lives of others and soon his guests come to exemplify those virtues also. This listening and learning, however, does not occur in isolation. Rabbi Gray never privileges the conceit of science--that science embodies all knowledge--and does not buy into the atomized model of human existence. He is always fully clear that his life has meaning through and because of (in no particular order) Chabad, Chani, the Rebbe, Judaism, Dartmouth, and the Jewish people. Why does the home of Rabbi and Chani Gray exude such warmth and acceptance? Why are is household shielded from the pernicious ideologies of the outside? The answer is remarkably simple and complex at the same time: the Rebbe.  It's hard to do justice to the life of the Rebbe. However, just a few minutes with Rabbi Gray are sufficient to see that the Rebbe, whom I believe he personally met, inspired this son of Judah to embark on a life of faith. The Rabbi always jokingly aggrandizes himself--he's his own best propagandist--but is always humble when speaking of the world and the life of the Rebbe. Though he would never admit it, the Rabbi is more like the Rebbe every time I meet him. It is clear that his encounter with the Rebbe encouraged him to devote his life to the existential pursuit of ethical and spiritual modes of life, and to helping everyone take up of the challenge of ethical living. The writings and the actions of the Rebbe, as well as the thoughts and life of Rabbi Gray, have as their starting point the concern of the Jews as a spiritual people. The Rebbe and the Rabbi always want to do right by the Jewish people above all else, and both sought the face of God for that right thing to do. Many would condemn this hyper-sensitivity to the fates of the Jewish people as ethnocentric and parochial. However, the ancient promise between God and Abraham holds true today "I will bless those that bless you and curse those that curse you." Again, "from Judah shall come salvation from the whole world." The Rebbe and the Rabbi begin with the Jewish people, but they do not end there. Their concern for the promises of God as revealed through the Jewish people allow them to occupy the universal speaking position where they seek the Torah-for-the-sake-of-heaven and can advise, love, and encourage all persons. The ironic and bitter lesson of the Rebbe's life and the Chabadic mission is that the divine blessing specifically stop flowing when the Jewish people forsake themselves. If the Rabbi were to forsake the Jewish people as his principle source of concern, he would lose his capacity for care for non-Jews. Thus, somemthing as universal of agape-love begins as parochial, particular concern contrary to the cosmopolitans and liberal political theorists. Like Christ, Jews must overcome the world and become the chosen people once again to remind everyone else to be is to be in the presence of God and of the significant others: friends and family. "Out of Egypt I have called my son" the prophet remarked of God's people; out of Dartmouth, the Rebbe and the Rabbi have called to all those who would listen. It was the Rabbi, Chani, Mendel, and Chabad who taught me that salvation begins after the overcoming. |