The Dartmouth Observer |

|

|

Commentary on politics, history, culture, and literature by two Dartmouth graduates and their buddies

WHO WE ARE Chien Wen Kung graduated from Dartmouth College in 2004 and majored in History and English. He is currently a civil servant in Singapore. Someday, he hopes to pursue a PhD in History. John Stevenson graduated from Dartmouth College in 2005 with a BA in Government and War and Peace Studies. He is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Chicago. He hopes to pursue a career in teaching and research. Kwame A. Holmes did not graduate from Dartmouth. However, after graduating from Florida A+M University in 2003, he began a doctorate in history at the University of Illinois--Urbana Champaign. Having moved to Chicago to write a dissertation on Black-Gay-Urban life in Washington D.C., he attached himself to the leg of John Stevenson and is thrilled to sporadically blog on the Dartmouth Observer. Feel free to email him comments, criticisms, spelling/grammar suggestions. BLOGS/WEBSITES WE READ The American Scene Arts & Letters Daily Agenda Gap Stephen Bainbridge Jack Balkin Becker and Posner Belgravia Dispatch Black Prof The Corner Demosthenes Daniel Drezner Five Rupees Free Dartmouth Galley Slaves Instapundit Mickey Kaus The Little Green Blog Left2Right Joe Malchow Josh Marshall OxBlog Bradford Plumer Political Theory Daily Info Andrew Samwick Right Reason Andrew Seal Andrew Sullivan Supreme Court Blog Tapped Tech Central Station UChicago Law Faculty Blog Volokh Conspiracy Washington Monthly Winds of Change Matthew Yglesias ARCHIVES BOOKS WE'RE READING CW's Books John's Books STUFF Site Feed |

Wednesday, December 21, 2005

Is Iraq Voting A Cause for Celebration? Last Thursday, the state of Iraq held a vote for a four-year government to replace the current interim parliament. This interim government was plagued by many problems, the least of which was it took the coalition leaders three months to agree on whom would get which jobs. Pundits and politicians hailed the vote as the beginning of democracy, and, a sign that the insurgency had finally begun to trade political power for violence. I'm not that optimistic for four reasons. (1) Our celebration may be some premature; voting is a signal that the Shiite and the Sunni believe that have something to gain from electoral contestation. Electoral contestation, as the Irish Republicans demonstrated many times over, can complement as well as substitute the armed struggle. (2) There are tactical as well as strategic reasons for voting. The German Wiemar Republic is a good example of "tactical democrats"-- political parties who participate in the parliamentary process long enough to gain legitimacy while undermining the foundations of democratic political rule. It is a positive thing, I think, that the international political climate has valorized voting and representational governments as more legitimate expressions of the political will. However, political leaders who aspire to lead their states are not fools; if voting is in, they are most certainly willing to allow, encourage, and participate in voting to make the Western European and North American intelligentsia happy. Egypt and Saudi Arabia are excellent examples of this. (3) The parties that America supported received small shares of the vote. The newest parties haven't been, and aren't, terribly supportive of American troops in their country; they call it an "occupation", a term that has regional cache given the Arab-Israeli dispute. Israpundit went so far as to suggest that "Iran won the Iraqi vote." (4) SecState Rice remarked that the process of national elections was a process in which the governors request the consent of the governed. "Two days from now, the Iraqi people will go to the polls for the third time since January. And they will elect a parliament to govern their nation for the next four years. All across Iraq today, representatives from some 300 political parties are staging rallies, they're holding televised debates, they're hanging campaign posters, and they're taking their case to the Iraqi people. They are asking for the consent of the governed." Is that true? Can we really say that political parties, particularly in very divided states, seek the consent of the governed? Or would it be more appropriate to suggest that the posturing and the platforms of the parties are designed to suggest that an election victory is a "mandate" for the party's agenda? Israel makes an excellent case in point. When one votes for the Likud, why exactly is one doing that? Or in America, what did it mean to vote for John Kerry in the last election? One might have simply not supported Bush, one might have been in favor of a balanced budget, or one might have agreed with the Democrat 2004 platform. All of this is simply to say that voting does not uniquely bring the specifics of the general political will into government, but does create a representative indicator of whether the country prefers more "liberal/secular" parties, more "Islamist" parties, etc. It doesn't tell us what the country wants in specific; and that is the largest problem of all. The insurgency is presumably fighting for something. Voting, without other aspects of democratic life such as the free press, a strong judiciary, a robust economy, an education populace, etc is not particularly helpful toward the goal of divining what it is the insurgency is fighting for. In fact, voting may encourage intransigence on the part of some of the political parties who mistake their "base"/constituency for permanent political support in the post-Hussein posturing. Tuesday, December 20, 2005

Alito Consistently Biased The Yale Law Students have released their report on Judge Alito and his jurisprudence. They are neutral in their representation of him and summarized their findings are trade-offs (e.g "In the area of civil rights law, Judge Alito consistently has used procedural and evidentiary standards to rule against female, minority, age, and disability claimants. He has taken a markedly different approach to religious discrimination, ruling in favor of religious minorities in various contexts.") but the larger picture is that this guy is really bad news. More in depth analysis later. PDF file is at YLSAlitoProjectFinalReport.pdf. Write your Senator to keep this guy off the courts. Just to let all you faithful readers know, the writers of the Observer are on intersession vacation between terms. This means updates won't be daily, but we do have a few more things to bring you before the end of the year. It is my hope to have a post about the "stipulation facts about racial discrimination" and to the rest of "Achieving Our Liberation." More as inspiration hits. Thursday, December 15, 2005

The Lamentations of a Dartmouth Alum Over at Balkanization, Mark Graber, who is apparently a Dartmouth alum, wrote a lament that can be summed up in this accurately cynical statement: "I rather doubt that Dartmouth frat boys will cry if ROE is overruled or change their behavior much. Nor, do I suspect, will the Wall Street Journal find that decision an occasion for mourning or celebration. If you can afford Dartmouth or read the Wall Street Journal regularly, ROE does not matter." I quote the post in full below but you should go look around their site as they, as well as I, have been thinking about "philosophical conservatism." I'm looking at Russell Kirk, but they've been reading John Kekes, whose book On Conservatism I absolutely loved. Conservative Elite and Abortion The Wisdom of Solomon The New Republic (registration required) had a very interesting piece about the liberal case for the Solomon Amendment. The amendment itself is apparently named after a late congressman named Gerald Solomon. For most of us, the late Gerald Solomon, a 20-year member of Congress, failed to leave a deep impression. A Google search on the man suggests a figure of modest historical impact, yielding articles such as "SOLOMON, ARDENT CONSERVATIVE, DIES." But dig a little deeper and other achievements emerge. The congressman regularly took up the fight against flag burning, once accusing an opponent on the issue, House Speaker Tom Foley, of "kowtowing" to the Communist Youth Brigade. He often expressed interest in the United Nations, opining that Kofi Annan "ought to be horsewhipped." And, when it came to bearing arms, Solomon's enthusiasm was unequivocal. "My wife lives alone five days a week in a rural area in upstate New York," he lectured fellow Representative Patrick Kennedy during a debate. "She has a right to defend herself when I'm not there, son. And don't you ever forget it." Some of the most elite law schools--the University of Chicago thankfully not included--have decided that the law abridges their freedom of speech, namely their opposition to "Don't Ask, Don't Tell." I obviously think don't ask, don't tell is a pile of horse pluckey equivalent to the ban the military once had against blacks and whites serving together. Nothing but empirical evidence--that's troops actually perform worse when they have a member whose gay in their squad--will convince me otherwise. The dispute at the heart of the lawsuit began in the 1990s, when the Association of American Law Schools (AALS) voted to include sexual orientation as a category meriting protection against discrimination. Employers who wished to recruit from law schools were obliged to comply with the same standard. Because the military has a near-ban on gays and lesbians, numerous schools chose to bar the Pentagon from recruiting on campus. In response, Congress, led by Solomon, voted to deprive schools of federal funding if they didn't allow military recruiters equal access. Things went back and forth for a while, but the eventual result was legislation allowing the government to withhold money from a university even if just one of its schools--a law school, say--restricts the access of military recruiters. However, the law schools are just being dumb. (Really, we expect better.) Their opposition stems from the fact that they want federal money and want to maintain their opposition to the anti-gay policies of the military by banning recruiters. Just give up the money and you can ban recruiters all you want. Morals can be costly. It's a strangely irksome little case, really--one of those disputes that take on a clumsy symbolism and touch unpleasantly on a variety of nerves, like a dentist's drill carelessly exploring a tooth. On one side you have an unfriendly law pushed by an old-fashioned jackass, God rest his soul, and on the other you have a group of educators marinating in self-righteousness. It's hardly an ideal set of heroes. However, the The New Republic makes a convincing case that "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" is doomed due to cultural pressure alone. Moreover, at the rate society is changing, the case may well be an anachronism within a matter of years. In the decade or so that the fight between Congress and the universities has been going on, there's been a dramatic cultural shift regarding gay rights. Let's remember: In 1997, when Ellen DeGeneres revealed herself as a lesbian on her sitcom, it was international news. Today, we have "Queer Eye" and "Six Feet Under," and no one blinks. A decade ago, not a state in the country offered same-sex civil unions; today, Vermont does, and Massachusetts has legalized same-sex marriage. More states look set to follow. TNR's Andrew Sullivan, in an article called "The End of Gay Culture," recently pointed out that 21 Fortune 500 companies offered benefits to same-sex couples in 1995; ten years later, more than 200 hundred do. And, while Red State America started from farther behind, it's rapidly progressing. Even Senator Rick Santorum, red as they come, has an openly gay director of communications. As Sullivan writes, "The speed of the change is still shocking." However, there's more at stake here than gay rights and equal recognition. (I apologize to those activists who assume that their rights are perhaps the most pressing issue.) This is about military recruiting at the best institutions. Even though the military is a backwards institution culturally, our national defense forces deserve a chance to convince the best American minds to join their team. I don't believe for a minute that educated, cultured people will torture less or be in any way more sympathetic (if anything, their ability to self-justify is greater). I do believe, however, the structure of opportunity disincentivizes military service for the cultural and intellectual elite, disproportinately shifting the burden to the lower classes. If anything, the lower classes have less, not more, reasons to fight for the American government (especially one headed by Bush). Far less heartening, by contrast, are the trends in military recruitment at top schools. No one among the classmates I knew in college would have been willing to take a few years to serve in the military while their friends were launching their lives and careers. This isn't simply selfishness; the entire structure of society discourages it. Charles Moskos, a Northwestern University sociologist who specializes in military issues, likes to point out that, in his Princeton class of 1956, over 400 students of about 750 served in the military. By 2004, that number was down to 8 students out of about 1,100. These numbers are for undergraduates, of course, not law school students. But the fact is that the entire culture of elite education--undergraduate, graduate, and professional--has grown hostile towards the idea of military service over the past 50 years. Permitting the Pentagon to puncture the self-imposed bubble of privileged schools is essential to changing this mindset. Supporting the Solomon Amendment means supporting the notion that our military should be representative of our society. The elites are more likely to go into policy making positions that will involve choices about using America's armed forces. Since most of them will not have studied security, hoping that some of them may have served might be the next best thing. Wednesday, December 14, 2005

Achieving Our Liberation, part III Note: This is the third in a series of posts, the whole of which might be a conference paper. Comments are encouraged on parts or on the whole. The Bound Nations from Europe’s Perspective Historically, the act of the imperialist and colonialist nations imposing the status of “colony” onto a people through military domination and economic exploitation constituted the source of national captivity. The predatory logic of capitalism drives its sponsor to create new markets and found exploitable labor power. This predation required both the domination of the colony and the submission of the local environments to the logic of capitalistic economics: competitive value-added production for a consumer base. Sartre, Lenin, and Cabral disagree, however, on exactly how imperialist capitalist logics dominate the colonies, and, as a result, disagree over what a project of national liberation would mean for the colonized. Lenin’s International Socialism: Nationalism as Weapon in the European Class Struggle Lenin, like Sartre, viewed imperialist domination as a function of capitalism. Unlike Sartre conceived of the hierarchical relationship from an international mode of life where capitalism had not, and indeed never fully would, become the dominant economic system of the world. Thus, imperialism was not only the domination of the colonized, but also the inevitable conflicts arising out of capitalist nations’ squabble over the divisions of a largely non-capitalist world. His most famous treatise on the matter described imperialism as the “highest stage of capitalism. (Lenin 1974, 78)” Imperialism was not the highest state simply because the best international capitalism could hope for was intra-capitalist competition over raw materials and cheap labor—Lenin indeed thought it was—but also because the furthest capitalism could hope to proceed was a core of capitalist nations dividing and transforming non-capitalist territories between them (Wood 2005, 126). Capitalism, and the imperialism it produced, Lenin fervently believed, would obsolesce into global socialism long before a majority of the world could become capitalist economies. Lenin’s internationalist perspective of imperialism also colored his view of nationalism and national liberation movements. Capitalist imperialism functioned to increase both commodity exchange, as in the days of classic colonialism, and capital production. The dependence of colonies on European finance capital would permanently bind the colonies and postcolonies to the European center in relations of economic dependency. According to Lenin, imperialism hastened the process of capitalist development in the colonies precisely to strengthen these dependencies (Lenin 1974, 128). Colonial nationalism, for Lenin, arises as a by-product of the imperialist-promoted capitalist development (Lenin 1974, 28). It is within this historical economic framework that national liberation movements arise to assist the imperialist nations with their transformation of a non-capitalist periphery into a productive part of the capitalist world-system. Throughout the world, the period of the final victory of capitalism over feudalism has been linked up with national movements. For the complete victory of commodity production, the bourgeoisie must capture the home market, and there must be political united territories whose populations speak a single language…The tendency of every national movement is towards the formation of national states under which these requirements of modern capitalism are best satisfied (Lenin 1974, 40-1). National states are the sign of the first period of capitalism—the triumph over the feudal order—and represent its awakening. “The typical features of the first period are: the awakening of national movements and the drawing of the peasants, the most numerous and the must sluggish section of the population, into these movements, in connect with the struggle for political liberty in general, and for the rights of the nation in particular (Lenin 1974, 45).” Nationalism is an excellent source of mobilization, and, in turn creates the desire for each nation to create its own state. Nationalism is dangerous because of its connect to reactionary elements: “The general “national culture” is the culture of the landlords, the clergy, and the bourgeoisie (Lenin 1974, 12).” The nationalism itself is a product of bourgeois culture, and it ultimately used in the service of spreading capitalism through imperialism. The countries of Asia, the greater part of whom Lenin identifies either as colonies or as depressed, dependent nations, best exemplified the historical link and logic of nationalism and capitalist development. Japan, the only independent national state in the region, had witnessed a speedy growth of capitalism, after which the bourgeois state began to “oppress other nations and enslave colonies. (Lenin 1974, 43)” The link between the bourgeoisie culture, capitalist development, and imperialism caused Lenin to distrust valorizations of these national liberation movements because they distracted the proletarians from their class struggle and threatened to divide the proletariat along national lines. “All liberal-bourgeois nationalism sows the greatest corruption among the workers and does harm to the cause of freedom and the proletarian class struggle…It is under the guise of national culture…that the Black Hundreds and the clericals, and also the bourgeoisie of all nations, are doing their dirty and reactionary work (Lenin 1974, 11).” The challenge, Lenin postulated, was to create a concept of national liberation that did not sell the working class revolution short. To do that, he turns to the fact of imperialist oppression to forge the tactical, though not ideological, alliance between the social democrats and the nationalists. “In every nation there are toiling and exploited masses” and the oppression of those masses give rise to the democratic claim of national self-determination as a claim against imperialism (Lenin 1974, 12). Narrowing the goal of liberation to the expression of a desire against exploitation served Lenin’s internationalism in three ways. First, it allowed him to situate national liberation in the progression of history from communalism to communism: “If we want to grasp the meaning of self-determination of nations…by examining the historico-economic conditions of national movements…the self-determination of nations means the political separation of these nations from alien national bodies, and the formation of an independent national state (Lenin 1974, 28).” Second, mere political separation constitutes a social democratic claim similar to the right of women to divorce their husbands and opposed only by critics on the right. “Just as in bourgeois society the defenders of privilege and corruption, on which bourgeois marriage rests, oppose the freedom of divorce, so, in the capitalist state, repudiation of the right to self-determination…means nothing more than the defense of privileges of the dominant nation and police methods of administration, to the detriment of democratic methods (Lenin 1974, 66).” Three, casting nationalist aspirations as particular manifestations of democratic dreams co-opts a potent source of mobilization from Lenin’s political adversaries. “Combat all national oppression? Yes, of course! Fight for any kind of national development, for “national culture” in general?—Of course not (Lenin 1974, 22-3).” Lenin feared that nationalists wanted to divide the worker’s movement to continue capitalist exploitation along national lines, a situation he saw as currently present in the United States. “In the Northern States Negro children attend the same schools as white children do. In the South there are separate “national”, or racial, whichever you please, schools for Negro children. I think that this” resulted from “the division of education affairs according to nationality (Lenin 1974, 25, 24).” Internationalism encouraged Lenin’s frigidity toward struggles for national liberation. Even though he mentions that it is the duty of socialists to aid revolutionary parties in their struggle against imperialism, even if these struggles took on a nationalist character, the struggles for nationhood were distractions from the struggle for social democracy and mere transitions along the path to world socialism (Lenin 1974, 113-14). The growing number of nationalist movements testified to the success of imperial capital awakening the need for national states; socialist assistance of this need aimed toward the imminent world revolution. The nationalisms of the peripheral, colonial, and depressed nations were important only as sites of armed resistance against capitalism. Oftentimes that imperial burden obfuscated the glorious mission of proletariat, observed Lenin in his reflections on Engels and Marx’s comments about the relationship between the British and Irish working classes (Lenin 1974, 81-4). Since “only the victories of the working class can bring about the complete liberation of all nationalities”, it is not surprising that Lenin observed “the English working class will never be free until Ireland is free(Lenin 1974, 82). ” Justice for the Irish, a subjugated nation at the time, is subordinate to the democratic aspirations of the working classes within the imperial nations. Lenin, however, as he was not entirely in the center himself—being a Russian during the Tsarist period—provided us with a means of overcoming Lenin’s unwillingness to equate the claims of justice for nations with the claims of justice within nations. Lenin admitted that the dynamics of the capitalist world system limited the potential democratic outcomes of successful struggles for national liberation. “The right of nations to self-determination [and] all the fundamental demands of political democracy are only partially “practicable” under imperialism [as a world-system], and [only] then in a distorted form and by way of exception. (Lenin 1974, 100). ” Lenin’s solution to the problem was inelegant: only until the social democratic state gave way to the Communist world order could true democratic aspirations blossom. However, Lenin’s observation that a world-system of imperialism, exploitation, and warfare limits the democratic character of national revolutions is important. This insight suggests that the concept of national liberation must aim to take the nation out of the world-system in which it emerges. Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Interpreting the Right to Bear Arms Many opponents of gun control argue that the Constitution protects ensurs that no one "infringes" on their right to bear arms as individual citizens. Gun control, in fact, could be a way to protect the right from the "infringement" of criminal behavior within American society. I don't find a strong argument in the constitutional text for gun control. The problem with the second amendment is that it is not written in a grammatically straight-forward way per our modern usage of English. Let's trot out the text and analyze the sentence: " A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” First, we can conclude that a well-regulated militia is necessary to the security of a free State given the position of the adjectival apposite in relation to the subject of the sentence: "A well regulated Militia." I'm certain that the Supreme Court or the Congress has, at some point, clarified the criteria concerning what it means to be a militia, and, what it means to be "well regulated." Second, the sentence is, presumably, about the subject "A well regulated Militia" and all subsequent clauses before the verb "shall" refer back to the subject. Third, this militia is necessary to the "security of a free State." It would, at this point, be appropriate to figure out how militia functioned as a social and security institution in colonial America because it is unclear whether the state whose freedom is preserved by the presence of the militia is a "state" like the United States, or a "state" like Wisconsin or New York. It would also tell us what "security" might have meant, given that the "security" of the country comes from the armed forces and the security of the people comes from the police. If "security" meant protection from the British, then the right to keep and bears arms is protected by the very fact that any citizen can join the armed forces in some capacity. If "security" meant stealing land from Indians and continuing a genocide, then we no longer face that condition and it could simply refer to the right of police persons to bear arms. (This reading would favor preventing the arming of slaves to foreclose the option of a slave rebellion.) The "right of the people to keep and bear Arms" occurs at a odd place grammatically due to the appositive immediately prior setting the general reason (to secure the freedom of the state). Given the supremacy of the militia as the subject of the sentence, there is textual evidence to believe that the right of the people was not a direct one, but a right that existing because of citizen access to certain institutions--the militia for the writers of this text and the armed forces/police for us. That would be consistent with two implementations of arms control laws, one historical, the other present. The fact that even after the Reconstruction Amendments blacks were forbidden to own and carry guns--even though most freedman purchased guns as a sign of their freedom--suggested that their collective right as a people to bear arms for their security existed through the occupying force of the standing army in the south. This would also be consistent with the demand of the Black Panthers to form all-black militias to protect African-Americans in the 1960s and 1970s from police brutality and racial terrorism. If it were a direct inalienable right of every person, rather a collective right of the people exercised through representative institutions like the armed forces, the police, or, for the Panthers, all-black militias, then we would not be able to restrict felons from owning guns. However, if their collective security is provided for by the police or the national army, then their right to bears arms is protected from the point of view of the text. If the right did not belong to the people, hired legions of mercenaries would be constitutionally permissible as a means of providing national or personal security. This means bodyguards might be illegal. Finally, we come to the small matter of what entails an "infringement" of the right to a well-order militia/ right to bear arms. This is underspecified in the text. However, the underspecification does not seem to preclude Congressional oversight (gun control) on the matter because we have to distinguish it from the phrase "congress shall make no law" which occurred earlier in the text (First Amendment). It seems to me that as long as the armed forces and police have the funding to provide for the security of the citizens the right of the people to bears arms for their security. Guns in the hands of citizens outside a well-regulated militia setting, then, are a threat precisely because giving the choice to an individual to use guns outside that structure decreases the security of the free state, and thereby strips the people of their rights to security under the Constitution. The second amendment, thus, may militate for gun control laws. Monday, December 12, 2005

Achieving our Liberation, part II Note: This is the second in a series of posts, the whole of which might be a conference paper. Comments are encouraged on parts or on the whole. The Bound Nations from Europe’s Perspective Historically, the act of the imperialist and colonialist nations imposing the status of “colony” onto a people through military domination and economic exploitation constituted the source of national captivity. The predatory logic of capitalism drives its sponsor to create new markets and found exploitable labor power. This predation required both the domination of the colony and the submission of the local environments to the logic of capitalistic economics: competitive value-added production for a consumer base. Sartre, Lenin, and Cabral disagree, however, on exactly how imperialist capitalist logics dominate the colonies, and, as a result, disagree over what a project of national liberation would mean for the colonized. Imperialism as a Cancer for Europe: Helping “Them” to Help “Ourselves” Sartre develops a theory concerning the colonial logic of the metropolitan producers and the settler-colonists. Europe and its interests are central to his story, and he never fully manages to think outside his mode of life. In one essay, “Colonialism is a System”, Sartre records the French method of colonial market-creation: the transplantation of excess European populations and the concentration of the means of production—land, labor, and capital—under the colonists’ control. His historical theoretical narrative about colonialism focuses on the dynamics and imperatives of surpluses in market economies, particularly surpluses of labor and goods. His narrative mentions the colonized in relation to processes begun in Europe. Sartre begins with the “first” definition of colonialism as expounded by Jules Ferry, “the great figure of the Third Republic”: It is in the interest of France, which has always been awash with capital and has exported it to foreign countries in considerable quantities, to consider the colonial question from this angle. For countries like ours which, by the very nature of their industry, are destined to be great exporters, this question is precisely one of outlets…Where there is political predominance, there is also predominance in products, economic predominance (Sartre 2001, 33). Ferry identifies the four key elements necessary as a prerequisite for a colonialist ideology: a country that defines itself as the center, surplus capital, strong export interests, and desire for economic predominance. Sartre criticizes the latter three, but misses the first. I shall come back to that later. However, he makes evident the ideological flaws at the core of Ferry’s glowing praise for France’s productive capacity: all of them center on the need for a passive, dominated colony. “The capital with which France is ‘awash’ will not be invested in under-developed countries”, Sartre insinuates (Sartre 2001, 33). France was searching for economic and political predominance. By investing in others France ran the risk of creating competitors and thereby threatened the very precondition of colonialism, “France…awash with capital.” Nevertheless, that surplus must go somewhere and the natives in the colonies cannot afford to purchase the surplus goods. That problem—of the lack of a buyer market—quickly resolves itself, Sartre wryly noted, when the settler becomes involved. “The concomitant of this colonial imperialism is that spending power has to be created in the colonies. And, of course, it is the colonist who will benefit from all the advantages and who will be turned into potential buyers. The colonialist is above all an artificial consumer, created overseas from nothing by a capitalism which is seeking new markets. (Sartre 2001, 34)” In this way, settler colonization becomes the physical method by which the territory of another nation is incorporated in the sphere of French political and economic dominance. The settler, however, arrives in a land owned by another people. Lacking any true normative or historical claim to the land, settlers have only two choices if they are to ground the new outposts of the French market: bribery and theft. In the sparsely populated regions of the country, settler colonization is less noticeable and takes the form of “military occupation and forced labor. (Sartre 2001, 34)” The most concentrated populations occupied and cultivated the most profitable land for France. The market, in the physical persons of the settlers, needed to acquire the land for the colonial system, and, as Sartre judiciously phrased it, “any method was acceptable. (Sartre 2001, 35)” French colonialists chose management techniques created and perfect by Spain when it invented America. Every crushed revolt, every land speculator, every law designed to break the traditional property relations of Algeria were also the elegant fingers of colonial-market-settlers tightening their grip on the land and choking the life of the indigenous people. “The results of the operation: In 1850, the colonists’ territory was 115, 000 hectares. In 1900, it was 1, 600, 000; in 1950, it was 2, 703, 000. Today [1956]…7 million hectares have been left to the Algerians…It has taken just a century to dispose them of two-thirds of their land. (Sartre 2001, 36)” For Sartre, colonialism’s dominative and dispossesive dynamics defined the relationship of the colonized and the colonizer. It also sustained support in the metropolis for colonialism among capitalists. In terms of sheer agricultural output, the French settlers out-produced the Algerians: “Agricultural production is estimated as follows: the Muslims produce 48 billions francs worth; the Europeans produce 92 billions francs worth. (Sartre 2001, 38)” The loss of Algerian colony would represent a loss of the investment of the profit. The system of capitalism, however, is not only the economic ties, dependencies and land-ownerships supported by the system, it is also the identities “colonialist” and “native” reified by the system in its own self-reproduction. The colonial system is not just the “million colonists, children, and grandchildren of colonists, who have been shaped by colonialism and who think, speak, and act according to [its] very principles”, it is also the fabricated native, composed of “his function and interests (Sartre 2001, 44).” However, Sartre shied away from describing precisely how the Algerian [man] is fabricated by the colonial system, and focused instead on the false consciousness of the colonialist whose homeland was France but whose country was Algeria. This is because Sartre ignores how the identity of France, and not just its economic interests, were bound into and by the France-colony identity. France’s quest for economic and political predominance meant that France first had to create a political economic system of which it was the center and author. The natives, fabricated though they were, were also always exterior to that system. French capital follows French settlers protected by French soldiers who gather the land using French law to sell French goods to French consumers. At no point was the colonial system anything but French. In fact, so distrustful and so presumptive was French colonialism that it incorporated Algeria into the political structure of France itself, and did its best to replace non-French identities with those of the French. The natives appear in Sartre’s story only to the extent which their presence confirms the self-defeating nature of French colonialism: “The Algerians…have decided to attack our political predominance…Colonialism is in the process of destroying itself…It is our shame; it mocks our laws or caricatures them. It infects us with racism (Sartre 2001, 44, emphasis added).” The goal of national liberation, from the center’s point of view, is to construct a better, less acerbic relationship between “a free France and a liberated Algeria” and to deliver France—oh, and Algeria too—from French colonial tyranny: “The only thing that we can and ought to attempt…is to fight along side [the Algerians] to deliver both the Algerians and the French from colonial tyranny (Sartre 2001, 47, emphasis in the original).” From the center’s perspective, imperialism is the unjust acquisition of land and appropriation of the value of the land by the surplus products of the metropolis. Concordantly, liberation entails the transfer of land, rents, and legal authority to the colonized people in order that the direct dominative relationship can end. It is an unhelpful view, as it does not envision a role for the postcolony outside of the world system. Sartre’s unexamined presumption of Europe as the center of world history—a position he evidences most clearly in his criticisms of Negritude in Black Orpheus—ultimately does not allow for the development of a true philosophy of national liberation. Friday, December 09, 2005

Achieving Our Liberation, I I've finally finished all my exams. We'll be returning to a full week of updates on Monday. I'll also be posting one of the essay I've recently written over the next few days for comments on any of the parts or the whole. As usual, all ideas are copyrighted by both by the DartObserver and by the individual authors. Freedom is a prerequisite for justice.* To say that American slaves experienced injustice is an understatement. The condition of slavery made it impossible to speak of justice in a true sense. Similarly, to say that no justice exists for an entire class of nations would be equally facile. Most scholars agree that today a world system exists, rooted in international capitalism. The more radical of those scholars would acknowledge that the international economic order privileges the political economic position of the strong over the positions of the postcolonial states. As evidenced by the growing tensions within the current Doha round of the World Trade Organization, and the concept of the North-South gap, the inability of postcolonial states to determine for themselves a future independent of the world system suggests that these nations lack freedom in any real sense. In trying to discern moral principles for “after the terror”—after the collapse of the twin towers in autumn of 2001—philosopher Ted Honderich 2002 writes of the conditions of the “half-lives” of many who live exterior to the world system as compared to their counterparts in its center. “Some people, because of their societies, have average lifetimes of about seventy-eight years. Some other people, because of their different societies, live on average about forty years.[…] For every 1,000 children born alive” in Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, and Sierra Leone “about 200 die under the age of five. A dark fact. An evil…” More than injustice, postcolonies have lived experiences than can be classified as evil in comparison to the opulence of those in the center of the world system. Equality, however, is not the central issue; even historically, the design and function of the international economic order has been to deny those societies choices outside the world system (Wood 2005). The central issue is freedom to determine one’s own path outside the imperial logics of the era of modernization, to over-come “the world-system itself, such as it has developed until today for the last five-hundred years. (Dussel 2003)” This conception of freedom forms what the philosopher-theologian Enrique Dussel calls an “ethic of liberation.” This ethic of liberation forms the core of politician and political theorist Amilcar Cabral’s reflection on the subject: “…[T]he chief goal of the liberation movement goes beyond the achievement of political independence to the superior level of complete liberation of the productive forces and the construction of economic, social, and cultural progress of the [nation]….(Williams and Chrisman 1994)” When applied to the nation, and this is my central argument, an ethic of liberation becomes a struggle for national liberation, which is the freedom of a postcolony to find political existence outside the world system according to its own history. This freedom is a prerequisite for justice. That is the lesson that the historical struggles for national liberation have for political theorists. The further we get from the proclamations of political independence, the more it seems that formal independence is distinct from national liberation, especially when we consider the imperial effects of a global system of capital (Wood 2005). Having defined national liberation as the ability of nations to leave the world system and find their own path, I aim to detail what national liberation, as a project, entails. I begin by describing how the nation is unfree in the thoughts of four theorists writing in a Marxist framework: Vladimir Lenin, Jean-Paul Sartre, Enrique Dussel and Amilcar Cabral. Understanding the nation’s captivity is crucial to understanding how the nation can emerge from the system. The theorists from the center, Lenin and Sartre, disagree vigorously with the theorists from the periphery over the meaning of liberation (Wallerstein 2003). This disagreement largely results from how each imagined liberation in relation to the capitalist system. Not all visions of liberation aim to imagine the postcolony outside of a world-system, and the tensions between the postcolony and the world-system drive the disagreements between the theories. Once I have identified the source of restriction on the nation, I shall offer reasons why a truly liberated postcolony must be exterior to the system. *I'd like to thank S. Luke Blair and Steven Wu for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this draft. If We Are All Equal, Why Do We Need Different Names? Do governments think that we liberals are dumb enough to believe that the second-class citizenship they are enforcing on gays (in the name of equality) is going to pass the bulls**t meter? Congratulations to all those gay couples poised to tie the knot, as the UK's new law permitting 'civil partnerships' comes into force. For those who want to pledge their undying love, it's nice that there is now a formal way of doing so; just as it is humane and practical to permit gay couples the legal rights that civil partnership will bestow. If its marriage, call it marriage. Surely the road to perdition is paved with good intentions; it would be nice to see action once in while though. What bothers me most, though, is why the sex lives of gay people are so important. The author suggests the government wants to regulate the bedrooms of gays--that may be true--but it seems to me that this whole fuss about marriage, pair-bonding, and true love, etc. are just more social fabrications people buy into to ameliorate the atomizing effects of society. In boiling the essence of marriage down to property and pension rights, the civil partnerships for gays strip marriage of its mystique. In refusing to call a civil partnership a marriage, this new law is denuded of any of the progressive properties it might otherwise have. And in hyping up the whole thing beyond any impact it has upon the homosexual population, the civil partnerships scheme is fast becoming a caricature of gay naff.When did we liberals come to accept heteronormativity and the capitalist nuclear family? Gay sex was once radical; now it's just passe, and, at times, a bore, or, even worst, an annoyance. I definitely support people making "commitments" and "life-long promises to each other" but if the struggle for gay marriage becomes another tool for some people to tell others how to live, then I must say liberated sex soon seeks a straitjacket to replace its fetters. Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Ummm...What's exactly does "disciplined" mean again? Is the extraneous adjective preceding democracy bothering anyone else in this news report? Myanmar's ruling generals on Monday opened a round of talks on drafting a new Constitution and steering the isolated country toward what the junta calls "disciplined democracy". First discipline, then freedom. It's democracy-lite junta-style. Is International Law Important? Exercepts from Robert Jackson's closing statement at Nuremberg: It is common to think of our own time as standing at the apex of civilization, from which the deficiencies of preceding ages may patronizingly be viewed in the light of what is assumed to be "progress." The reality is that in the long perspective of history the present century will not hold an admirable position, unless its second half is to redeem its first. These two-score years in the twentieth century will be recorded in the book of years as one of the most bloody in all annals. Two World Wars have left a legacy of dead which number more than all the armies engaged in any way that made ancient or medieval history. No half-century ever witnessed slaughter on such a scale, such cruelties and inhumanities, such wholesale deportations of peoples into slavery, such annihilations of minorities. The terror of Torquemada pales before the Nazi Inquisition. These deeds are the overshadowing historical facts by which generations to come will remember this decade. If we cannot eliminate the causes and prevent the repetition of these barbaric events, it is not an irresponsible prophecy to say that this twentieth century may yet succeed in bringing the doom of civilization. Monday, December 05, 2005

So You Want Oversight on the War on Terror... Slate makes an excellent case that the merit of Bush's judicial nominees have less to do with whether they will overturn Roe or not--Slate believes they won't--but whether they are capable and willing to oversee the administration's war on terror. Pretend, for a minute, that I am not completely paranoid and that there is truth behind my sense that we are all missing the real story of the new Supreme Court nominations. My fear is that we are all snoozing through an elaborate plan to pack the court for the Bush administration's war on terror. What if all the obsessive talk about whether candidates are for or against overturning Roe v. Wade is a strategic head feint? What if I am right, and Samuel Alito is confirmed to the Supreme Court without ever substantively answering a question about torture, enemy detentions, the rights of foreigners, or civil liberties during wartime? Read the entire article and write your senator. Let's make sure we're not going to drop the ball on this one. Slow Week This is going to be a slow week with no sweeping philosophical tracts until I have my papers done. I've finished project one of three, mostly done with number two, and have gestured toward a coherent thought for three. I'll limit myself to quick updates about random thoughts and links as I read the news. I'll be back on the circuit when I have the luxury to have more good ideas than deadlines (as Andrew Samwick so eloquently phrased it). Thursday, December 01, 2005

This Day, The Day of My Birth I am proud to have been born on this day, which is also World AIDS Day. AIDS is, perhaps, the greatest threat to peace in our time. Blackprof.com gives us the details: Today is World AIDS day. More than 20 million have died worldwide and some 40 million are living with HIV/AIDS. The scale of the devastation is so immense that it’s difficult to comprehend. This disease continues to affect people of color disproportionally. In the US, there may be 1.2 million affected. 43% are black, 35% white, and 20% Hispanic. Globally, 26 million of the 40 million are from Africa. In some countries like South Africa, it is estimated that 20% of the adult population is affected. The Dartmouth Observer: Blogging Styles There's a great entry over at Mister Snitch on blogging styles. We've been blogging just long enough (not quite a year now) to have spotted at least seven distinct types of traffic-generating blogging styles. After watching the blog market for a while, Snitch decided to create a typology of how people blog and how this might relate to their site traffic. In so far as the Dartmouth Observer has been bringing you (awesome) content since the Summer of 2002, but has only recently been providing you daily content since mid-October 2005, I want to offer what I think ChienWen and my blogging styles are. In July we might re-evaluate and extend to some of our own writers from ages past. Feel free to comment. ChienWen falls into the following categories: 3 and 7 3) Nichebloggers, aka localbloggers. We've posted on local blogging before. Local bloggers focus on their locality, but we also consider someone focused on any particular subject a "local" blogger (that subject being the 'locality'). The subject is usually something the writer is passionate about, or has special expertise in. Econbrowser is a great niche blogger, specializing in macroeconomics. Some 'niche' bloggers switch their 'locality' from time to time. Dan Riehl is an important 'local' blogger whose 'locality' for some time has been Natalee Holloway. When another story of size comes along, he may switch to a new 'locale'. I, John Stevenson, am probably a mixture of 1 and 7, with an occasional 3. Since you already know what 3 and 7 are, I give you 1. 1) Meme-du-jour bloggers comment on the high-profile ideas of the moment. This requires more or less constant research, and results in posts that are often less than polished or complete (because they have to be composed quickly, and also because these stories are after all, developing). This type of blogger is usually focused on political issues. The analysis of blogging is excellent and I offer that you should read it. Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Country Before Party Prime Minister Arik Sharon, known for his legendary gambles as a general, left his a political party he found, the Likud, to make a new one, Kadima (forward). But's that not the real news. Former Prime Minister and vice premier Shimon Peres has left the Labor Party, a party he's served as head of and prime minister of at least three times, to join Sharon's party. This might not necessarily be a good a thing for Israeli politics and the peace process for four reasons. One, there has been a Washington consensus around the Israeli question since Sharon formed a coalition unity Labor-Likud government. There are generally three splits in the political elite on who to support in Israel. (It is a virtually unanimously held opinion, outside the CIA and State Department, that American support for Israel should go unchallenged.) Hardliners in America prefer Netanyahu, who had a portfolio in the government until trying to challenge Ariel Sharon for power. The hardliners, however, remained appeased due to the formidable Likud presence in the Sharon government. Centrist Republicans and Democrats prefer Peres, the Olso peace process, and the Labor party. As long as they were in the coalition government, there was no reason to criticize the actions of the government. Finally, there were the realists, who supported the Sharon disengagement plan and the Road Map. UPI offers that the breaking of this consensus will rock Washington. By abandoning the Likud party that he helped to found 32 years ago and forming a new third party, Kadima, in the center of Israel politics, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon has broken the consensus that held American politicians of both parties, from President George W. Bush to Sen. Hillary Clinton, D-N.Y., loyal to the Sharon government. Even if they had qualms about Sharon, Democrats like Clinton were reassured by the presence of veteran Labor Party leader Shimon Peres in the governing coalition alongside Sharon. When the Labor party withdrew from the government after Amir Peretz became head of Labor, there was a real potential that the Israeli electorate and American elites would rethink our relationship to the failed pursuit of peace in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The UPI believes that Sharon's move will allow the EU to exercise greater flexibility. Shimon Peres' move to join Kadima and support Sharon changes all that. Two, Peres' support not only complicates a renewed debate over the peace process within Israeli and American politics, it is also draws the upper middle class (generally Ashkenazim Jews), who would likely support Peres, against the poorer Sephardi Jews who usually vote for Likud but to whom Peretz is appealing for new voters in the Labor party. As the UPI details, Peretz is using his Sephardic credentials to bring those voters to him: "Peretz is a Sephardi Jew from a North African background, and thus able to appeal to that crucial voting block of Sephardi Jews, many of them working class, who have been critical to Likud's support. And by stressing social spending, jobs and wages, Peretz is trying to change the terms of Israel's political discourse away from security (where Sharon is so powerful) to economics (where Sharon and Netanyahu are very vulnerable)." If two problematic cleavages in Israel--the ethnic rivalries of the Ashkenazim, the Sephardi, and the Russian Jews as well as the class rivalries of the semi-socialist Israeli state--codify and crystallize into party affiliation, the Israeli political sphere could become even more fractured than it already is. Three, Peres' departure takes those upper middle class votes from from the Labor party, which has increasingly started its outreach to Arab-Israelis. The extent to which Labor becomes a repository of rage against an Ashkenazim-dominated state is the extent to which Israeli discourse is going to take a dramatic turn, for the worst. Four, and finally, Peres and Sharon's decision represent a consensus within the founding generation about their mistrust about the motives and abilities of the younger Israeli leaders. The two men [Sharon and Peres] are both part of Israel's "founding generation" and they've been good friends for decades. Both Peres, who is 82, and Sharon, who is 77, have little faith in the new generation of Israeli leaders. They believe together they can secure some kind of agreement with Palestinians over the establishment of two states. This is all to say: Peres is Sharon's blessing--and problem right now. Even though Peres suggested that he was putting country before party, many, on the left and right, have interpreted this as just another political move to guarantee his continued power. Tuesday, November 29, 2005

The Holy See takes a New Look To Gay Catholics: In case you hadn't noticed, your church just flushed any remaining dignity you had down the toilet. Not only are you sinners--even some Protestant churches, I'm afraid agree with that statement--but you can't even become priests. A life of celibacy isn't enough to prevent you from undermining the "God-given" (read: politically-fabricated) values of the Church in Rome. You are only OK if you "discovers his homosexuality after having been ordained." So it's best, in the eyes of the Holy See, if you save your sexual experimentation until after ordination. To Bi-curious Catholics: Your life isn't as worse as the gays; for that rejoice. If your homosexual experience has been "transitory"--all you two beer queers out there--fear not. If you would simply end your curiosity and get back on the straight and narrow path--emphasis I'm presuming on straight because the road to hell is not only wide, it's gay too--you'll be saved again. "What must I do to be saved?" "Stop being gay and come to church." To the American Catholic Church: Please forget all this pretense about the church being universal and united under Rome. After all, Catholic doesn't mean universal any more; we just another denomination like the Mormons or the Protestants. And the Reformation was so dreadfully long ago; unity was overrated them and is overrated now. It's most important that you just keep coming to church and leave the politics to the bishops. Given this, I would like to inform you the head bishop of America, William S. Skylstad who is also president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, is as openly supportive of Rome as possible given his disagreement with the Church. His spin on the document? "Gay-inclined are cut some slack." Skylstad, 71, who has led the Diocese of Spokane since 1990 and has been a bishop since 1977, said the question of whether "homosexually inclined men" can be good priests depends on how they live and what they teach. Translation: It's important that you remain committed to being celibate priests not having sex while continuing to affirm the centrality of fertile heterosexual copulation. What does all this "slack" mean? The rope around your neck chafes more than it chokes. Skylstad urges church leaders to have a "comprehensive discussion" about the affective, or emotional, maturity of every candidate for the priesthood. Oh, and in case you were wondering about what "deep-seated [homosexual] tendencies meant: "the prohibition against men with "deep-seated tendencies" means a person actively looking at pornography or visiting gay bars would not be acceptable in the priesthood, but simply having an attraction to men would be. supporting gay culture means that a seminarian is "so concerned with homosexual issues that he cannot sincerely represent the church's teaching on sexuality." Monday, November 28, 2005

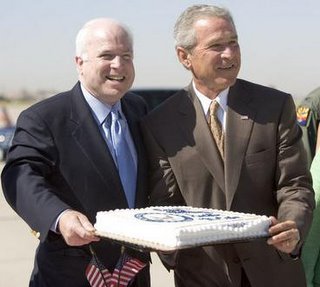

Hating Bush, Fisking McCain After the failures of the Bush Administration, conservatives are lining up for a home-run hero; they don't want any more false conservatives. Bush, who was thought to have arguably remade the Republican Party until the Miers revolt, has betrayed "conservatism" on every account, particularly when it comes to fiscal issues. For the more snobbish and intellectually-inclined conservatives, references to Edmund Burke or Russel Kirk are obligatory. Jeffery Hart, professor emeritus of English at Dartmouth, presents an excellent example "conservative" anti-Bush vitriol in his latest op/ed entitled, "George W. Bush, Bogus conservative." George W. Bush is not a conservative, but a right-wing ideologue who steers by abstractions in both foreign and domestic policy. Inevitably a perilous gap opens between his abstractions and concrete realities. Hart's analysis was precious, right down to the "wheeee" at the end of a paragraph about Tom Delay. What is most amusing, and instructive about this retrospective, ad hoc conservatism is that Locke doesn't get to make the cut whereas FDR does. When did FDR become a conservative? I think another "wheeee" is in order. More importantly, when was Locke kicked out of the conservative pantheon of saints? Stephen Bainbridge, law professor, whom I will upbraid in a moment, quotes Russell Kirk who wrote, "... the true conservative does stoutly defend private property and a free economy, both for their own sake and because these are means to great ends." Locke, particularly as he was invoked by Robert Nozick in Anarchy, State, and Utopia, the bible of libertarian conservatism, was one of the first theorists to defend the right to property at almost all costs. In fact, for Locke, the beginning of liberty was the ability to input value into property. Locke so thoroughly believed in the right of property that he even defended British colonialism in America on the contention that British settlers would add value to the land, and that this right of property transcended any government's ability to interdict or interfere. Locke was definitely a conservative. Conservative fury over Bush, moreover, has also led to the beginnings of the campaigns pre-2008 against Senator John McCain. Stephen Bainbridge on that point wrote: I get all schizo when I think about John McCain. I admire his life story and I think his "national greatness" version of conservatism is an interesting take on the problems of the day. But there's so much about him that drives me nuts. Ultimately, I can't imagine supporting him in light of: Stephen Moore's piece can be summed up in this paragraph: [McCain] views himself, I believe, as a kind of modern-day Robin Hood, a defender of the downtrodden and tormentor of the bullying special interests, which is endearing and unquestionably a big part of his broad political appeal, but often leads to populist and parasitic economic policy conclusions like higher taxes on the rich and attacks on "huge oil profits." He wants to be the caped crusader against corruption. The buzzword for the McCain Straight Talk Express in 2008 will be reform: "I want to reform education, reform Medicare and Social Security, reform lobbying and campaigns. Reform immigration. Reform. Reform. Reform." Bainbridge then, after trotting out a quote by Russel Kirk, concludes that McCain's reformist tendencies aren't truly conservative--I'm wondering how that squares with his statement at the beginning of post "his "national greatness" version of conservatism is an interesting"--and that ultimately we should avoid McCain if we want a "real" conservative in the White House. Now McCain's conservatism, and I'll prove that it's conservative in another post some other time, is summed up his view about immigration: "America must remain a beacon of hope and opportunity. The most wonderful thing about our country is that this is the one place in the world that anyone--through ambition and hard work--can get as far as their ambition will take them." All of the evils Bainbridge attributes to McCain come from the senator's basic willingness to prevent the uncaring titans of capitalism and government from choking out the ambition of drive of individual Americans. And it is this ability of individuals to make a fate and a living for themselves that makes America great in the McCain vision. For McCain, the malefactors of great wealth, a ballooning national deficit, and a badly managed war in Iraq all limit the ability of this country to be great. And I can't see why conservatives should disagree with that. Friday, November 25, 2005

Nuremberg's Continuing Importance The Nuremberg trials of the Nazis after World War Two are arguably the bedrocks of international law. The Nation memorialized Telford Taylor, a Nuremberg prosecutor who died in 1998, as the man to whom the "human rights movement owes much of its legal foundation. . . [Taylor's work in] Nuremberg gave legitimacy to the concept that the world had something to say about how governments treat their own citizens. In 1950 the United Nations codified Nuremberg's most important statements into seven Nuremberg Principles, which have since been adopted by the legal systems of almost every major nation." Wikipedia suggests the conclusion of Nuremberg led to four important conventions now considered sacrosanct in international law: (1) The Genocide Convention, 1948, (2) The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, (3) The Convention on the Abolition of the Statute of Limitations on War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, 1968, and (4) The Geneva Convention on the Laws and Customs of War, 1949; its supplementary protocols, 1977. Eric Posner, a professor of law at the University of Chicago, criticizes the Nazi war crimes tribunal by suggesting that the judgements of Nuremberg are not law in any meaningful sense. If Posner is correct, then all of the conventions, treaties, and norms that declare Nuremberg as their inspiration are legally smoke and mirrors. Let us begin with Posner's comments on Nuremberg. After that, I shall briefly point out some flaws in Posner's critique and offer why Nuremberg is still important. Posner's observations crystallize around three points. One, Nuremberg was a legal act in only the thinnest sense. The "legal" basis of Nuremberg stemmed directly from a policy paper, the London Charter, and was nothing more than a "sensible, politically expedient decision [disguised] as a moral judgment." Any enforcement of this policy paper would be political and not truly legal. Posner himself develops that point most succinctly: "Involvement of lawyers and judges does not convert an administrative procedure into a legal procedure, much less convert a political act into a tribute to Reason, at least not in any morally important sense." Two, contrary to Jackson's assertions, the Allies did not stay hand of vengeance in any meaningful way. By the time the war ended, the Soviets, the British, and the Americans had bombed thousands of German civilians and massacred millions of German troops. Those Germans who were fortunate enough to survive watched the victors divide their country and rape the women while the neighboring countries purged their territories of Germans. There was indeed vengeance, Posner argues, and the Germans felt it. Three, Posner continues, Nuremberg tried the leaders as symbols of Nazi criminality and forced them to give account and take responsibility for the atrocities they caused. The allies made no attempt to try, detain, arrest, and indict all those responsible for the war and for implementing the dictates of the National Socialist party--indeed they could not if they wanted Germany to continue as viable nation. Pragmatism demanded that "thousands of culpable nationalists and militarists were permitted to resume ordinary life." Trying the symbols of the failed regime, Posner concludes, "might have been sensible from an administrative perspective, from a public relations perspective...[or even] politically shrewd under difficult circumstances. But it was not a great moral victory, much less a vindication of the rule of law." In fact, the limitations and expediency of the entire Nuremberg process, in that "it did not establish an effective international rule of law that would constrain states over the next half century," suggests that its celebration as "one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason" is unwarranted. Gary Bass's, a professor of political science at Princeton, work on Nuremberg is useful for contextualizing Posner's point about the postwar situation. He wrote a book entitled, appropriately enough "Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals", and came here to the University of Chicago, at Eric Posner and Eugene Kontorovich's invitation to present his work at the International Law workshop. Bass maintains that war crimes tribunals, of which Nuremberg was not the first or the last, are messy affairs, especially "if one wants to get rid of undesirables; using the trappings of a domestic courtroom is a distinctly awkward way to do it. Sustaining a tribunal means surrendering control of the outcome to a set of unwieldy rules designed for other occasions, and to a group of rule-obsessed lawyers. These lawyers have a way of washing their hands of responsibility for the political consequences of their own legal proceedings." Postwar diplomacy is messy and legal rules and trappings don't help. So why use war crimes tribunals? Bass develops the answer at length: The core argument...is that some leaders do so because they, and their countries, are in the grip of a principled idea....Some decision makers believe that it is right for war criminals to be put on trial—a belief that I will call, for brevity's sake, legalism. In fact, even though Winston Churchill wanted to shoot all the Nazis after the war, President Roosevelt right before the Yalta conference, had become persuaded by the need for a case to document the crimes of the Nazi regime. Stalin agreed with Churchill's basic sentiment of shooting Nazi leaders but quipped, "In the Soviet Union, we never execute anyone without a trial." Churchill agreed saying, "Of course, of course. We should give them a trial first." All three leaders issued a statement in Yalta in February, 1945 favoring some sort of judicial process for captured enemy leaders. Stalin and Churchill's support of the trials, however, were only intended as cover for doing what they wanted to do anytime: stick it to the Germans and the Nazis for their third major war in seventy years. The British and American judges, however, saw the point differently, and were committed to a fair process. Justice Robert Jackson conceded that although whether to hold trials or not was a political question. "It's a political decision as to whether you should execute these people without trial, release them without trial, or try them and decide at the end of the trial what to do. That decision was made by the President, and I was asked to run the legal end of the prosecution", once the politicians had decided in favor of trials, the rule of law should reign supreme. Jackson, in his discussion with negotiators from the other nations, further stipulated: "What we propose is to punish acts which have been regarded as criminal since the time of Cain and have been so written in every civilized code." This might have, and indeed did, lead to some leaders being acquitted under the rules established for the proceedings. In fact, as Bass pointed out in the workshop--between making fun of my purple hat--the Soviet judges, accustomed to rubber-stamping the political decisions of the Communist party, were upset when their British and American colleagues voted to acquit some Nazi leaders. For the Americans and the British, the tribunals represented the postwar moment where, through legal proceedings and the rule of law, the vengeance expected on the battlefields and in the prison camp was bracketed and sublated into the rules-governed adversarial process of legal adjudication. The Soviets, on the other hand, saw trials, massacres, and shootings as equal opportunity tools of a victor's justice of vengeance. Leaders were tried before they are shot--the judicial legitimates the political and the violent--;the soldiers and POWs were executed and deported; the women, at the mercy of the soldiers, were raped to atone for the German crimes of aggression; and the industry and workers of E. Germany, where the Soviets reigned supreme, were shipped back to the homeland to aid in the cause of socialism. Posner pointed out that some militarists went back into civilian life because we couldn't catch them all. That was only really true in W. Germany; in the east, the Communists, after spending years in the prison and death camps, sought to purge Germany of the fascist militarism, and largely did through the wholesale slaughter and internment of a good portion of the adult population. Does it matter that even in W. Germany, Nuremberg wasn't really law in the way that American domestic law is law? Not really. That Nuremberg took the form of law and legal processes was important--that it was a vindication of the rule of law was less central to the lessons of Nuremberg. Posner is disappointed because Nuremberg was essentially legal enforcement of a policy decision. But the strength of Nuremberg is not the fact that it's good law--Posner's right on that point--but that it underscored the importance of (1) using lawyers, judges, and legal processes to carry out politically sensitive jobs and (2) time-bounded institutions as means of resolving delicate questions. First, because of the professional importance of following rules and procedures, and, more importantly, creating legitimacy for their actions, legal processes and languages have become important ways of cooling down hot potatoes. What do we do with Saddam, Milosevic, and Pinochet? We could shoot them; it's probably more than they deserve. No, instead, the United States wants to try them and demonstrate, plainly for all to see, that like Eichmann, these men are not just criminally culpable, they represent a type of evil in the international system that can only be contained by leaders who submit their authority to the rule of law. Like Eichmann, Napoleon, or any of the others leaders tried before tribunals, Pinochet, Milosevic, and Hussein "never aspired to be villains. Rather, they over-identified with an ideological cause and suffered from a lack of imagination or empathy: they couldn't fully appreciate the human consequences of their career-motivated decisions." Even American presidents have done atrocious things in the name of power politics--Bush I watched the Kurds die and Nixon destroyed many countries in South Asia--but ultimately the rule of law, in this case elections and threat of impeachment--removed the cancerous sores from the American polity. Second, these temporally specific institutions, established to do one job, grant states and non-state actors a place where they can create political frameworks designed to deal with a specific situations. This political understandings often create convergence around new normative frameworks--like the principle of distinction or the concept of genocide after Nuremberg--that give state leaders rhetorical tools to legitimate their actions and non-state actors normative tools to mobilize support and criticize states. Legal process are the best forms of institutional legitimation and power to accomplish the resolution of delicate political questions. |